Why the West Rules--For Now (68 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Chinese intellectuals, I suspect, would have been astonished to hear of this idea. Laying down their inkstones and brushes, I can imagine them patiently explaining to the nineteenth-century European historians who dreamed up this theory that twelfth-century Italians were not the first people to feel disappointed with their recent history and to look to antiquity for ways to perfect modernity. Chinese thinkers—as we saw in

Chapter 7

—did something very similar four hundred years earlier, looking back past Buddhism to find superior wisdom in Han dynasty literature and painting. Italians turned antiquity into a program for social rebirth in the fifteenth century, but the Chinese had already done so in the eleventh century. Florence in 1500 was crowded with geniuses, moving comfortably between art, literature, and politics, but so was Kaifeng in 1100. Was Leonardo’s breadth really more astonishing than that of Shen Kuo, who wrote on agriculture, archaeology, cartography, climate change, the classics, ethnography, geology,

mathematics, medicine, metallurgy, meteorology, music, painting, and zoology? As comfortable with the mechanical arts as any Florentine inventor, Shen explained the workings of canal locks and printers’ movable type, designed a new kind of water clock, and built pumps that drained a hundred thousand acres of swampland. As versatile as Machiavelli, he served the state as director of the Bureau of Astronomy and negotiated treaties with nomads. Leonardo would surely have been impressed.

The nineteenth-century theory that the Renaissance sent Europe down a unique path seems less compelling if China had had a strikingly similar renaissance of its own four centuries earlier. It perhaps makes more sense to conclude that China and Europe both had Renaissances for the same reason that both had first and second waves of Axial thought: because each age gets the thought it needs. Smart, educated people reflect on the problems facing them, and if they face similar issues they will come up with similar ranges of responses, regardless of where and when they live.

*

Eleventh-century Chinese and fifteenth-century Europeans did face rather similar issues. Both groups lived in times of rising social development. Both had a sense that the second wave of Axial thought had ended badly (the collapse of the Tang dynasty and rejection of Buddhism in the East; climate change, the Black Death, and the crisis of the church in the West). Both looked back beyond their “barbarous” recent pasts to glorious antiquities of first-wave Axial thought (Confucius and the Han Empire in the East; Cicero and the Roman Empire in the West). And both groups responded similarly, applying the most

advanced scholarship to ancient literature and art and using the results to interpret the world in new ways.

Asking why Europe’s Renaissance culture propelled daredevils to Tenochtitlán while China’s conservatives stayed home seems to miss the point just as badly as asking why Western rulers were great men while Easterners were bungling idiots. We clearly need to reformulate the question again. If Europe’s fifteenth-century Renaissance really did inspire bold exploration, why, we should ask, did China’s eleventh-century Renaissance not do the same? Why did Chinese explorers not discover the Americas in the days of the Song dynasty, even earlier than Menzies imagines them going there?

The quick answer is that no amount of Renaissance spirit would have delivered Song adventurers to the Americas unless their ships could make the journey, and eleventh-century Chinese ships probably could not. Some historians disagree; the Vikings, they point out, made it to America around 1000 in longboats that were much simpler than Chinese junks. But a quick glance at a globe (or

Figure 8.10

) reveals a big difference. Sailing via the Faeroes, Iceland, and Greenland, the Vikings never had to cross more than five hundred miles of open sea to reach America. Terrifying as that must have been, it was nothing compared to the five thousand miles Chinese explorers would have had to cross by sailing with the Kuro Siwo Drift from Japan, past the Aleutian Islands, to make land in northern California (following the Equatorial Counter Current from the Philippines to Nicaragua would mean crossing twice as much open sea).

Physical geography—and, as we will see later in this chapter, other kinds of geography too—just made it easier for western Europeans to cross the Atlantic than for Easterners to cross the Pacific. And while storms might well have blown the occasional Chinese ship as far as America

*

—and the North Equatorial Current could, conceivably, have

brought them back again—it was never likely that eleventh-century explorers, however motivated by Renaissance spirit, would find the Americas and return to tell the story.

Only in the twelfth century did shipbuilding and navigation improve to the point that Chinese ships could have reliably made the twelve-thousand-mile round-trip from Nanjing to California; but that, of course, was still nearly four hundred years before Columbus and Cortés. So why were there no twelfth-century Chinese conquistadors?

It may have been because China’s Renaissance spirit, whatever exactly we mean by such a term, was in retreat by the twelfth century. Social development stagnated and then tumbled in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and as the preconditions for Renaissance culture disappeared, elite thought did indeed turn increasingly conservative. Some historians think the failure of Wang Anshi’s New Policies in the 1070s turned Neo-Confucian intellectuals against engagement with the wider world; some point to the fall of Kaifeng in 1127; others see the causes in entirely different places. But nearly all agree that while intellectuals continued thinking globally, they began acting very locally indeed. Instead of risking their lives in political infighting at the capital, most stayed home. Some organized local academies, arranging lectures and reading groups but declining to train scholars for the state examinations. Others drew up rules for well-ordered villages and family rituals; others still focused on themselves, building perfection one life at a time through “quiet sitting” and contemplation. According to the twelfth-century theorist Zhu Xi,

If we try

to establish our minds in a state free of doubt, then our progress will be facilitated as by the breaking forth of a great river … So let us now set our minds on honoring our virtuous natures and pursuing our studies. Let us every day seek to find in ourselves whether we have been remiss about anything in our studies and whether or not we have been lax about anything in our virtuous natures … If we urge ourselves on in this way for a year, how can we not develop?

Zhu was a man of his times. He turned down imperial offices and lived modestly, establishing his reputation from the ground up by teaching at a local academy, writing books, and mailing letters explaining his ideas. His one venture into national politics ended in banishment and

condemnation of his life’s work as “spurious learning.” But as external threats mounted in the thirteenth century and Song civil servants cast around for ways to bind the gentry to their cause, Zhu’s philosophically impeccable but politically unthreatening elaboration of Confucius started to seem rather useful. His theories were first rehabilitated, then included in state examinations, and finally made the exclusive basis for administrative advancement. Zhu Xi thought became orthodoxy. “

Since the time

of Zhu Xi the Way has been clearly known,” one scholar happily announced around 1400. “There is no more need for writing; what is left is to practice.”

Zhu is often called the second-most-influential thinker in Chinese history (after Confucius but ahead of Mao), responsible, depending on the judge’s perspective, either for perfecting the classics or for condemning China to stagnation, complacency, and oppression. But this praises or blames Zhu too much. Like all the best theorists, he simply gave the age the ideas it needed, and people used them as they saw fit.

This is clearest in Zhu’s thinking on family values. By the twelfth century Buddhism, protofeminism, and economic growth had transformed older gender roles. Wealthy families now often educated their daughters and gave them bigger dowries when they married, which translated into more clout for wives; and as women’s financial standing improved, they established the principle that daughters should inherit property like sons. Even among poorer families, commercial textile production was giving women more earning power, which again translated into stronger property rights.

A male backlash began among the rich in the twelfth century, while Zhu was still young. It promoted feminine chastity, wifely dependence, and the need for women to stay in the house’s inner quarters (or, if they really had to go out, to be veiled or carried in a curtained chair). Critics particularly attacked widows who remarried, taking their property into other families. By the time Zhu Xi thought was rehabilitated in the thirteenth century, his pious ideal of re-creating perfect Confucian families had come to seem like a useful vehicle to give philosophical shape to these ideas, and when bureaucrats began rolling back property laws that favored women in the fourteenth century they happily announced that it was all in the name of Zhu Xi thought.

Zhu’s writings did not cause these changes in women’s lives. They were merely one strand of a broader reactionary mood that swept up

not just learned civil servants but also people who were most unlikely to have been reading Zhu. For instance, artisans’ representations of feminine beauty changed dramatically in these years. Back in the eighth century, in the heyday of Buddhism and protofeminism, one of the most popular styles of ceramic figurines was what art historians rather ungallantly call “fat ladies.” Reportedly inspired by Yang Guifei, the courtesan whose charms ignited An Lushan’s revolt in 755, they show women solid enough for Rubens doing everything from dancing to playing polo. When twelfth-century artists portrayed women, by contrast, they were generally pale, wan things, serving men or languidly sitting around, waiting for men to come home.

The slender beauties may have been sitting down because their feet hurt. The notorious practice of footbinding—deforming

little girls

’ feet by wrapping them tightly in gauze, twisting and breaking their toes in the interest of daintiness—probably began around 1100, thirty years before Zhu was born. A couple of poems seem to refer to it around then, and soon after 1148 a scholar observed that “

women’s footbinding began

in recent times; it was not mentioned in any books from previous eras.”

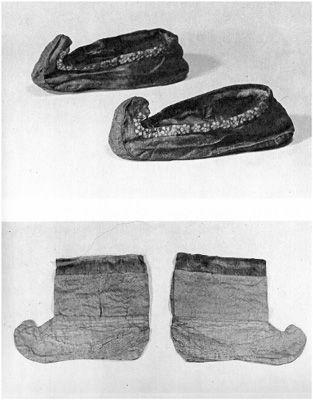

The earliest archaeological evidence for footbinding comes from the tombs of Huang Sheng and Madame Zhou, women who shuffled off this mortal coil in 1243 and 1274, respectively. Each was buried with her feet bound in six-foot-long gauze strips and accompanied by silk shoes and socks with sharply upturned tips (

Figure 8.9

). Madame Zhou’s skeleton was well-enough preserved to show that her deformed feet matched the socks and sandals: her eight little toes had been twisted under her soles and her two big toes were bent upward, producing a slender-enough foot to fit into her narrow, pointed slippers.

Twelfth-century China did not invent female foot modification. Improving on the way women walk seems to be an almost universal obsession (among men, anyway). The torments visited on Huang and Zhou, though, were orders of magnitude greater than those served up in other cultures. Wearing stilettos will give you bunions; binding your feet will put you in a wheelchair. The pain this practice caused—day in, day out, from cradle to grave—is difficult to imagine. In the very year Madame Zhou was buried, a scholar published the first known criticism of footbinding: “Little girls not yet four or five, who

have done nothing wrong, nevertheless are made to suffer unlimited pain to bind [their feet] small. I do not know what use this is.”

Figure 8.9. Little foot: silk slippers and socks from the tomb of Huang Sheng, a seventeen-year-old girl buried in 1243, the first convincingly documented footbinder in history

What use indeed? Yet footbinding grew both more common and more horrific. Thirteenth-century footbinding made feet slimmer; seventeenth-century footbinding actually made them shorter, collapsing the toes back under the heel into a crippled ball of torn ligaments and twisted tendons known as a “golden lotus.” The photographs of the mangled feet of the last twentieth-century victims are hard to look at.

*

Blaming all this on Zhu Xi would be excessive. His philosophy did not cause Chinese elite culture to turn increasingly conservative; rather, cultural conservatism caused his ideas to succeed. Zhu Xi thought was just the most visible element of a broader response to military defeat, retrenchment, and falling social development. As the world turned sour in the twelfth century, antiquity became less a source of renewal than a source of refuge, and by the time Madame Zhou died in 1274 the sort of Renaissance spirit that might drive global exploration was sorely lacking.