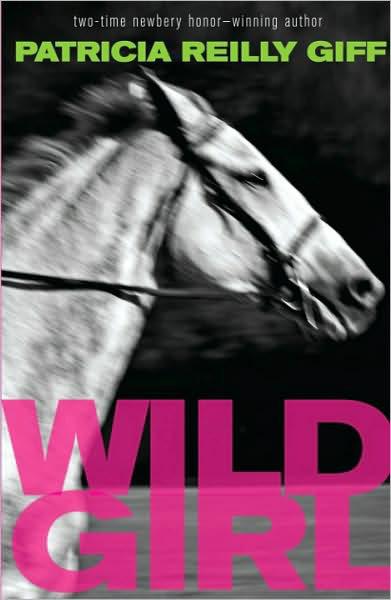

Wild Girl

Authors: Patricia Reilly Giff

PATRICIA REILLY GIFF

FOR MIDDLE-GRADE READERS

Eleven

Water Street

Willow Run

A House of Tailors

Maggie’s Door

Pictures of Hollis Woods

All the Way Home

Nory Ryan’s Song

Lily’s Crossing

The Gift of the Pirate Queen

The Casey, Tracy & Company books

FOR YOUNGER READERS

The Kids of the Polk Street School books

The Friends and Amigos books

The Polka Dot Private Eye books

For Caitlin Patricia Giff,

beautiful Caitie, with love

1

AIKEN, SOUTH CAROLINA

Sudden light burst against the foal’s closed eyes. She needed to open them, and to get on her legs, which trembled under her. It was the only thing she knew, that struggle to stand

.

And a feeling of warmth, the smell of warmth

.

She opened her eyes and heaved herself up under that dark shape. Its head turned toward her, a soft muzzle, a nicker of sound

.

Milk. Rich and hot

.

She could see almost in a full circle. Another creature was nearby, its smell unpleasant, but she turned back to the mare

.

When she was filled with milk, she leaned against the mare; she felt the swish of the mare’s long tail against her face. She opened her mouth and felt the hair with her tongue

.

Safe

.

JALES, BRAZIL

My bedroom seemed bare without the horse pictures. Small holes from the thumbtacks zigzagged up and down the walls.

Tio Paulo would have a fit when he saw them.

Never mind Tio Paulo. I tucked the pictures carefully into my backpack. “You’re going straight to America with me,” I told them.

Everything was packed now, everything ready. I was more than ready, too, wearing stiff new jeans, a coral shirt—my favorite color—and a banana clip that held back my bundle of hair. My outfit had taken almost all the

dinheiro

I’d saved for my entire life.

“You look perfectly lovely,” I said to myself in the mirror, then shook my head. “English, Lidie. Speak English.” I

started over. “You look very—” What was that miserable word anyway?

Niece?

Who could think with Tio Paulo downstairs in the kitchen, pacing back and forth, calling up every two minutes, “You’re going to miss the plane!”

I took a last look around at the peach bedspread, the striped curtains Titia Luisa and I had made, the books on the shelf under the window. But I had no time to think about it; there was something I wanted to do before I left.

I rushed downstairs, tiptoeing along the hall, past Tio Paulo in the kitchen, and stepping over Gato, the calico cat who was dozing in the doorway.

Out back, the field was covered with thorny flowers the color of tea, and high grass that whipped against my legs as I ran. I was late. Too bad for Tio Paulo. He’d have to drive more than his usual ten miles an hour.

I whistled, and Cavalo, the farmer’s bay horse, whinnied. He trotted toward me, then stopped, waiting. I climbed to the top of the fence and cupped my fingers around his silky brown ears before I threw myself on his back.

“Go.” I pressed my heels into his broad sides and held on to his thick mane.

Last time

.

We thundered down the cow path, stirring up dust. My banana clip came off, and my hair, let loose, was as thick as the forelocks on Cavalo’s forehead.

We reached the blue house where we’d lived when Mamãe was alive. I didn’t have to pull on Cavalo’s mane; he knew enough to stop.

The four of us had been there together: Mamãe, my older

brother, Rafael; my father; and me. And it was almost as if Mamãe were still there in the high bed in her room, linking her thin fingers with mine.

The three of you will still belong together, Lidie, you’ll make it a family

.

Shaking my head until my hair whipped into my face, I had held up my fingers:

There are four of us, Mamãe. Four

.

I remembered her faint smile.

Ai, only seven years old, but still you’re just like your father, the Horseman

.

Just like Pai.

Two weeks later, Mamãe was gone, flown up to the clouds to watch over us from heaven, Titia Luisa said. And Pai and Rafael went off to America, leaving me with Titia Luisa and Tio Paulo. I still felt that flash of anger when I thought of their leaving without me.

I ran my fingers through Cavalo’s mane.

I’m going now, Mamãe. Pai has begun to race horses at a farm in America, and there’s room for me at last. Pai and Rafael have a house!

“Goodbye, blue house.” The sound of my voice was loud in my ears. “Goodbye, dear Mamãe.”

Tio Paulo was outside in the truck now, blasting the horn for me.

“Pay no attention to him,” I whispered to Cavalo.

Cavalo felt the pressure of my knees and my hands pulling gently on his mane, and turned.

We crossed the muddy

rio

, my feet raised away from the splashes of water, and climbed the slippery rocks, Cavalo’s heels clanking against the stone.

In the distance, between his yelling and the horn blaring, Tio Paulo sounded desperate.

Suddenly I was feeling that desperation, too. We had to

go all the way to São Paulo to catch the plane. But I was determined. Five minutes, no more. “Hurry,” I told Cavalo.

Up ahead was the curved white fence that surrounded the lemon grove. The overhanging branches were old and gnarled, the leaves a little dusty, and the lemons still green.

Pai, my father, had held me up the day he’d left. His hair was dark, his teeth straight and white.

“Pick a lemon for me, Lidie. I’ll take it to America.”

I’d reached up and up and pulled at the largest lemon I could find.

“When I send for you, you’ll bring me another,”

he’d said.

What else was in that memory? Their suitcases on the porch steps, and I was sobbing, begging,

“Take me, take me.”

He’d scooped me up, my face crushed against his shirt, and his voice was choked.

“This is the worst of all of it,”

he’d said. In back of him, Luisa was crying, and Tio banged his fist against the porch post.

But that was the last time I cried. After they left, I promised myself I’d never shed one more tear. Not for anyone. I told myself I didn’t care whether Pai ever sent for me. I tried to ignore that voice inside my head that said how much I missed him, and how I longed to see my brother, Rafael.

Instead, I rode Cavalo all over the fields of Jales, I climbed out my window to sun myself on the sloping roof, I swam in the

rio

even though the water turned my fingers to ice.

Maybe that was why Tio Paulo told me a million times: “You may be small, Lidie, but how difficult you are.”

“And tough as

ferro,”

I’d say back, raising my chin high.

Titia Luisa would laugh, smoothing down my hair,

“You’re not like iron, Lidie. You’re like an orange, hard on the outside, but sweet inside.”

Tio Paulo and I would look at each other, eyes narrowed; neither of us believed it.

Now I reached out, my fingers touching the dusty leaves of the tree. I could hear the horn blaring as I twisted off the nearest lemon and held it to my nose. Then I let Cavalo know with my knees that we had to race for home.

Cavalo took the fence easily, and we galloped back, the swish of the grass in my ears, a startled bird flying up.

I slid off Cavalo and put my arms around his warm neck, my face against his mane. “I’ll miss you,” I said. “Miss me, too.”

I reached into my pocket for a peppermint. “I love you.” I held it out, feeling his soft muzzle on the palm of my hand as he took it from me. Then I climbed the fence and ran toward the truck that would take me away from Jales.

TO JOHN F. KENNEDY

INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

At the airport in São Paulo, Titia Luisa stayed in the truck, tears streaming down her face. “I can’t bear to see you go, Lidie.” She touched my hair, my shoulders, and I leaned against her for just a moment.

Tio Paulo was not in the mood for goodbyes. He hurried me inside, circling around knots of people. “A fine thing if you missed the plane.”

“I’ll just sit here and wait for the next one,” I said as we stood at the end of an endless line. I waved my hand. “You don’t have to stay.”

“You’d be safe.” He tried not to grin. “Who’d want to kidnap you, anyway?”

“They’d be happy to have me,” I said, and was horrified to hear how much I sounded like him.

We checked in, then listened to an announcement that said the plane was delayed for an hour. Tio was in a fit of a mood now, and so was I.

We sank into the last two seats against the airport window. “You see,” I said, “we didn’t have to have hysterics, and rush like crazy after all.”

Tio Paulo snorted. “You remind me of your father.” He pulled at his mustache.

I narrowed my eyes. “You remind me of Cavalo when he has a burr in his foot.”

We were sandpaper against sandpaper.

“You …,” he began, and then we both couldn’t help laughing.

“I’ll miss you after all,” he said gruffly.

“Me too.” My voice was so low, I wondered if he’d heard me. We were silent for a while. Then Tio spoke. “Do you want to know how your father became a citizen of New York?” he asked. “The customs people at the airport thought he might have false papers. They put him into prison until the next day.”

My eyes widened in spite of myself. “They thought he was a criminal?”

Tio’s fingers began again, smoothing his mustache. “No, no. The papers were real. Everyone apologized. It was fine.”

Suddenly my flight was announced. We hugged awkwardly before he handed me over to the flight attendant who would take me through security. Just before I turned the corner, I looked back at him over my shoulder. He was still standing there, his hand half raised. I gave him a quick wave.

On the plane, I waited to see what it would feel like to fly.

In no time, the ground was speeding by below me: brown earth, spikes of grass, a crane spreading its pale wings. The trees became a smudge of green …

And I was in the air.