Wild Hares and Hummingbirds (10 page)

Read Wild Hares and Hummingbirds Online

Authors: Stephen Moss

I

N THE GARDEN

, spring has arrived bang on time. The morning of the vernal equinox dawns bright, sunny and warm. Today is one of only two occasions each year when the entire globe experiences twelve hours of daylight and twelve hours of darkness – give or take the transitions at dawn and dusk. And for most of us, it marks the first day of the most exciting, jam-packed and eventful season in the calendar: spring.

To celebrate this moment of global unity in their own small way, my children have chosen to leave the comfort of the sofa and play outside, in the garden. They are astonished – as am I – by the sudden appearance of crocuses and daffodils, which seem to have sprung up overnight, as if the long spell of ice and snow just a few weeks ago never

happened

. Bumblebees flit from bloom to bloom, while a pair of buzzards takes advantage of the rising temperatures, and the thermal air currents they produce, to soar high into the morning sky.

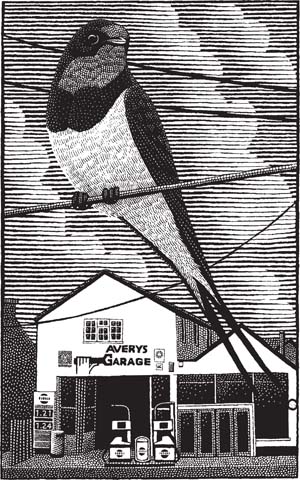

But for me, this jigsaw of spring still has a few pieces missing. The swallows that chatter above next door’s farmyard are still somewhere well to the south of here; as are the vast majority of other returning migrants. But one summer visitor should be here; and this morning, as I tread carefully across the dew-laden grass, I shall surely hear it.

Things might be easier if I could temporarily silence the other birds: the rooks cawing constantly from the top of the ash trees; the robins singing their sweet song, and the song thrushes their more deliberate one; the dunnocks’ warble, and the blue tits’ chatter.

I strain my ears – is that it? No, just another blue tit. And then, 50 yards to the east, from the far side of our neighbour’s garden, the sound that, for me, marks the true arrival of spring finally reaches my ears.

Chiff-chaff-chiff-chaff-chiff-chaff …

Yes, it’s the bird which makes identification easy by singing its own name: the chiffchaff. Chiffchaffs are one of the first migrants to arrive back here each spring, usually reaching our parish in the third week of March. They have not had as far to come as some of their cousins: their closest relative, the willow warbler, travels from the southern tip

of

Africa, whereas most of our chiffchaffs spend the winter in Spain, Portugal or North Africa.

Indeed in recent winters, chiffchaffs have sometimes stayed put, usually in the south-west, where milder winters mean there are still small insects to be found. But most still make the short but potentially hazardous journey from the other side of Europe; and I’m pleased that this one, at least, has made it through.

Chiffchaffs aren’t the most colourful or striking of birds, being small, slender and olive-green in colour, with no obvious distinguishing field-marks. Yet for me they have a real charm, perhaps because I associate them so closely with the start of my favourite season. Within a week or two my garden – and gardens and hedgerows throughout the British countryside – will be echoing to the sound of chiffchaffs from dawn to dusk, a sound we shall continue to hear throughout spring and summer. So another piece of spring’s jigsaw is firmly in place; with many more to come.

Meanwhile, the buzzards have soared almost out of sight; two brown specks hanging motionless in the clear blue sky.

T

HE GRASS IS

getting greener, the shadows are becoming shorter, and the clocks go forward tonight to mark the start of British Summer Time. I am passing through

the

southern part of the parish, whose wide open fields contrast with the more enclosed area around my home. Among the gulls and swans gathering in the rough pasture, I notice, in the far distance, three medium-sized brown lumps. Not clods of earth, but hares; March hares, indeed.

In this part of Somerset, you can’t get away from hares. Leaping hares, boxing hares, hares with huge, floppy ears. Sadly these are not real, but either painted, sculpted or cast in bronze. If you want a picture or a paperweight, a key ring or a fluffy toy, or even a bottle of beer named after a hare, I can find you one. The real thing is a little bit trickier.

As in much of the rest of Britain, we have a glut of the hare’s close relative, the rabbit. Cycling around the lanes and droves of the parish, I see them everywhere: running, sitting, lolloping … does any other animal, apart from the rabbit, lollop?

Now, you may be of the opinion that there isn’t much difference between a rabbit and a hare – in which case you’ve surely never seen a real, live hare. For compared with a rabbit, a hare is a Ferrari, not a Ford Focus; a Michelangelo, not a Rolf Harris; a Pelé, not a Vinnie Jones – in short, as close to the epitome of grace, beauty and style as any wild animal has a right to be.

Even before a hare moves, its shape tells you this is no ordinary creature. As it hunches close to the ground, ears twitching, its energy is barely contained. As soon as

it

springs into action the sense of length is palpable: long ears, long legs and long body, which somehow all fall into proportion as the animal explodes into speed. The tail is small and dark-tipped, not like the rabbit’s showy powder-puff; and the sheer power of an animal which can run almost twice as quickly as the fastest human being on earth is simply awesome.

The hare’s speed is just one of its armoury of weapons against predators. Another strategy is to lie flat against the ground in a shallow depression known as a ‘form’. The hare’s apparent ability to vanish completely, allied to the knowledge that they don’t dig burrows, led to the animal being granted magical qualities. And because, like most mammals, hares are largely nocturnal, they are not seen so often during the day. All this helps explain our long love affair with this mysterious and elusive creature.

It took me a while before I even saw a hare here in the parish. My wife Suzanne had come across them, as she drove the children to nursery along Kingsway, the long, winding road which joins the centre of the village to the A38. The children had seen them too, reporting this to me with great excitement.

But it was not until I took to my bicycle, and began to explore the back lanes behind my home where the ground rises up towards the villages of Chapel and Stone Allerton, that I finally stumbled across a group of hares. Even then, I almost cycled straight past – at first mistaking them for the usual rabbits. Once I realised what they were, though,

I

was able to stalk them by crouching down behind the camber of the field.

They hid well: body flat, ears down, and stock-still, apart from a nervous twitch of their huge, brown eyes. When I finally got too close, their ears pricked up, the black tips twitching like a sprinter waiting for the starting gun. Then they were off, in an explosion of movement; from stasis to speed in a fraction of a second. I was left frustrated at the brevity of our encounter, yet also elated that I had seen them at all.

Hares are usually regarded as ‘one of ours’: a native animal, contrasting with the alien rabbit, which was brought to Britain for food by the Romans. Yet we now know that the hare was brought here too – probably even earlier than the rabbit, during the Iron Age. But perhaps because, unlike the rabbit, it has never reached pest proportions, we are more inclined to regard it as a true Brit.

Hares are most famous for their habit of boxing, especially on bright, cold days in early spring, earning them the unfortunate epithet ‘Mad March Hare’. Like so many things about hares, we haven’t got this one quite right. This is not, as is often assumed, rival males fighting over a female; but the female testing out her suitors to see if they are up to the job. As so often in nature, when it comes to courtship, it is the female’s preference that matters, not that of the male.

I

T IS THE

last day of March, exactly one quarter of the way through the year. And although a casual glance could lead you to assume that the landscape has hardly changed since the start of January, the wildlife of the parish has undergone dramatic, and in many cases life-changing, experiences.

New Year frosts, followed by January snows, February thaws and March winds, have all taken their toll. But those plants and animals which have managed to survive are now ready to embark on the roller-coaster journey of spring. During the next three months, a rush of new life will change the face of the landscape and its wildlife, as birds and mammals, flowers and insects, reptiles and amphibians, trees, mosses and lichens respond to the lengthening hours of daylight, and the growing warmth of the sun.

And of all the changes I shall witness, the next month, April, will see the most dramatic and profound.

ON EASTER SUNDAY

, the cross of St George flies proudly above the church tower, battered by a stiff north-westerly breeze. Inside the thick stone walls, the Reverend Geoffrey Fenton preaches his Easter sermon. Outside, another form of resurrection continues apace: the onslaught that is the arrival of spring.

Clear blue skies, studded with a few low clouds, belie a chill in the air as I venture outdoors for a morning bike ride with the children. The sound of what they call the ‘teacher bird’, the syncopated song of the great tit, permeates the landscape; competing with the trill of wrens, descant of chaffinches, and the clear, pure tones of the latest arrival, the blackcap. In a willow tree by the rhyne at the bottom of the lane, a pair of chiffchaffs is setting up territory. They flit around the pale green catkins, continually pumping their tails up and down to keep their balance.

As we head back home, the children trailing their bikes behind them, the sunlight catches a small bird as it flies low over the grassy field by Perry Road. It is a shape at once familiar, yet strangely unfamiliar, for I haven’t seen it for almost half a year. It is a returning swallow: my first of the spring.

I feel almost tearful as I realise that my emotional allegiance has been transferred from another returning migrant. Having lived half my life in suburbs and cities, for me the swift was always the bird that marked the true coming of summer. But now, in my fifth year in

the

countryside, I have shifted my loyalty to the swallow, whose constant twittering, from April to September, provides a seasonal soundtrack to our lives here in the village.