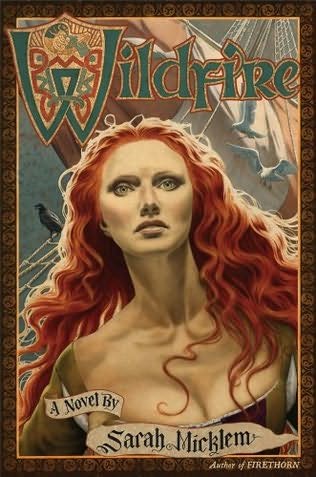

Wildfire

Authors: Sarah Micklem

SARAH MICKLEM - WILDFIRE

PROLOGUE Wildfire

CHAPTER 1

Thunderstruck

CHAPTER 2

Marked

CHAPTER 3

Oracle

CHAPTER 4

The Black Drink

CHAPTER 5

Daughters of Torrent

CHAPTER 6

March

CHAPTER 7

Snowbound

CHAPTER 8

The Summoning

CHAPTER 9

Mischief

CHAPTER 10

Raiders

CHAPTER 11

Shiver-and-Shake

CHAPTER 12

Council of the Dead

CHAPTER 13

Travail

CHAPTER 14

Lynx

CHAPTER 15

Corvus

CHAPTER 16

Boarsback Ridge

CHAPTER 17

Lost

CHAPTER 18

Sapheiros

CHAPTER 19

The Manufactory

CHAPTER 20

Tharais

CHAPTER 21

The Bathing Room

CHAPTER 22

White Petals

CHAPTER 23

The Dowser

CHAPTER 24

Thrush

CHAPTER 25

The Quickening

CHAPTER 26

Court of Tranquil Waters

CHAPTER 27

House of Aghazal

CHAPTER 28

Taxonomies

CHAPTER 29

Whore-Celebrant

CHAPTER 30

The Hunt

CHAPTER 31

Alopexin

CHAPTER 32

Moonflower

CHAPTER 33

The Serpent Cult

CHAPTER 34

Adept

CHAPTER 35

Katabatons Cleft

Acknowledgments

PROLOGUE

Wildfire

I

disobeyed. I followed Sire Galan to war, though he had commanded me to go home. Hed been generous, granting me the use of a stone house on a mountainside for all of my days to come. But how could I call it home, a place Id never seen? A blanket and the ground to lie on with Galan beside me, that was the home I claimed. It didnt suit me to be put aside, judged too weak to endure what lay ahead. I set my will against Sire Galans, hazarding that if I did as I pleased, I might also please him.

Hed charged his horsemaster, Flykiller, with the duty of herding me home, along with the warhorses Galan had won in mortal tourney and was forbidden to rideall of us to be turned out to pasture. But I gave Flykiller the slip during the armys embarkation: two days of shouting and cursing, mules balking on gangways and men falling overboard, baggage and soldiers gone missing. In such confusion only thieves had been sure of their duties. I took refuge with my friend Mai, and set sail under the copper banners of the clan of Delve.

So I found myself now aboard a ship crossing a sullen green sea. Wretched, queasy, beset by misgivings. I lay curled up on deck, one leg heavy on the other, the bones bruising the flesh. My sheepskin cloak was sodden, and from time to time a drop of seawater crawled down my back. The ship creaked under us like an old alewifes hip joints, and stank of bilgewater, dung, salted fish, and the pungent pitch that coated the planks and rigging.

Before we left Corymb, the priests had prayed for a wind from north-of-east, the domain of Rift, and the god of war had been pleased to send it. For four days this strong cold wind had driven the fleet apace toward the kingdom of Incus. The ships went heavy laden, but we rode no lower in the water for bearing the weightiest cargo of all, Rifts banes: war, dread, and death.

Yet the war had commenced without us. A tennight ago King Thyrse in his wisdom had sent a small force of men ahead across the Inward Sea to

make landfall at the port of Lanx; Sire Galan and his clansmen of Crux were among them. The king had called them a dagger. A dagger is your best weapon for treachery, and by treachery they were to pass the citys gates, for the kings sister, Queenmother Caelum, had allies to let them in. By now theyd taken Lanx or failed in their purpose. In two or three days, if the wind stayed willing, wed know their fate, and therefore our own, whether we would face a sea battle and siege, or the grudging welcome owed to conquerors.

The ship was crowded. Idle foot soldiers sat on the rowing benches, dicing and quarreling for amusement. Mai and I had laid claim to a small space behind the mainmast, between great baggage chests fastened to the deck, and wed stretched a canvas overhead to make a shelter. Two of her nine children accompanied her on this campaign: her only son, Tobe, and third-daughter Sunup to look after him. We all suffered from Torrents hex, seasickness, which made Sunup listless, and Tobe fretful, and gave me a qualmish stomach. Mai suffered the most. Shed always seemed to me as strong as she was stout, and she was stout indeed. But her strength had dwindled quickly at sea, and I was more troubled than I was willing to show.

I sat up beside Mai and leaned against a baggage chest. She was white about the nostrils and her round cheeks had turned yellow as an old bruise. There was sweat on her brow despite the wintry chill in the air. She had her arms clasped over her midriff. She grimaced at me and said, I think Mouse is trying to thump his way out.

I put my palm against the hard hill of her belly and felt the kicks of the child she carried within. A boy, Mai claimed, for the way he rode high, and she thought hed come about the time of Longest Night, nearly a month away. Shed named him Mouse because she swore he had too much Mischief in himMischief, the boy avatar of the god Lynx, who goes everywhere accompanied by a scurry of mice. I knew she dreaded this birth, for her last child had been stillborn after a long and dangerous travail, and it seemed to me the name was a poor jest and an ill omen. But Mais wit was ever on the sharp side.

I leaned over and whispered to Mouse, Too soon, little one. Have patience.

Let him come, I dont care, Mai said. Hell split me in two if he gets any bigger. Besides, sick as I am, I couldnt feel worse.

Hush. I nodded toward Sunup, who lay next to me with her head under a blanket. She was not yet eleven years of age, and such talk might frighten her.

Shell know a womans travail soon herself. Time she learned about it.

Tobe was cradled in a coil of tarry rope covered with old grain sacks,

with Mais old piebald dog dozing beside him. Now the boy sat up and began to wail. I took him on my lap and wrapped his cold feet in a fold of my kirtle. Mai had suckled him for two years and only just weaned him, and he still clamored for the tit. I gave him a bit of dried apple to chew, and hugged him. Spoiled or not, he was sweet enough to nibble on.

Sire Torosus came to see Mai, walking along the narrow gangway where whiphands paced to make the oarsmen keep the beat when the winds were not so obliging. He jumped down beside us, and the piebald hound bowed before him and wagged his mangy tail back and forth. Sunup and I moved over so that Sire Torosus could sit beside Mai. He was narrow where Mai was broad, and she was taller by a forehead. But if a man dared say to Mais face that they were mismatched, she would wink, saying Sire Torosus was big where it counted. And when the man made some lewd boastful answer, as he always did, shed chase him away with her raucous laugh, saying, Its his heart thats big, ladI wager yours is the size of a filbert, and just as hard!

Sire Torosus put his hand on Mais leg. She kept her face averted and said, I beg you, go away. Im not fit to be seen.

Youre too vain. He gave her a buss on the cheek, and she flapped her hand at him.

Tobe squirmed in my lap and reached out for Sire Torosus, who let him stand upright on his knees and use his beard as a handhold.

Sire Torosus said to me, Is there nothing you can do for Mai?

It pained me to have to show him my palms, empty of comfort. All my remedies, all my herb lore, had failed. I could cool a fever with my hands, but the hex of Torrent Waters was a cold, wet malady, and I was powerless to draw out the chill that had settled deep inside Mai.

Sunup asked her father, Is she going to die? She had the pinched look of fear.

Of course not, he said, and I met his eyes for a moment.

I said, I never heard seasickness was mortal, only that it made folks wish they were dead.

Sire Torosus said to Mai, Wont you come to the cabin, my dumpling, and lie on the featherbed?

He had a berth in the sterncastle with the other cataphracts and armigers of the Blood. Mai had told me she was made to feel unwelcome when she tried to stay there with the children. She touched his arm, but still she wouldnt look at him. Its stifling inside. Not a breath of air that doesnt stink.

He sighed and gave Tobe back to me.

Fifteen years theyd been together, Sire Torosus and Mai. He had a wife, of course, and an heir of his Bloodjust as Sire Galan did, who had married a year ago and promptly sired a son. But Sire Torosus was never long from Mais bed, and they had nine living children to prove it. She was his sheath, and I daresay a truer wife to him than the one hed left at home.

Sheath

had a filthy sound in mens mouths, being another byname for a womans quim, like mudhole or honeypot. But that was the name we went by, those of us who had taken up with a warrior of the Blood or a mudborn soldier and followed him to war, each of us sheath to a blade. From sheath to whore was but a little slip. Often it happened that a woman took a chance on some likely man who lured her with fine promises and caresses, only to find herself at his mercy, lent or sold to his companions. Id taken such a chance, and it was my good fortune that Sire Galan had proved jealous rather than generous when it came to sharing my favors.

A two-copper whore, without even a blanket of her own, envies a harlot who serves only men of the Blood, who in turn envies a sheath who must please one man only, and above all the sheath of a cataphract such as Sire Galan, the most admired hotspur among the hotspurs of the army. I had merely to stand near him to shine by reflection. I didnt pride myself on thisto be eminent among the despised was still to be despised. But Id chosen to be Galans sheath and I would do the same if it were mine to do over; I ought to be brazen, and wear the word

Other books

The Innswich Horror by Edward Lee

Deadly Engagement: A Georgian Historical Mystery (Alec Halsey Crimance) by Brant, Lucinda

The Lynnie Russell Trilogy by R. M. Gilmore

The Ninth Floor by Liz Schulte

The Floating Girl: A Rei Shimura Mystery (Rei Shimura Mystery #4) by Sujata Massey

Taken by Dee Henderson

Little Nelson by Norman Collins

The Annals of Unsolved Crime by Edward Jay Epstein

This Tangled Thing Called Love: A Contemporary Romance Novel by Astor, Marie

The Master Falconer by Box, C. J.