Will Eisner (22 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Comics would limp along for nearly two decades, staying within the framework of the code at the cost of insipid stories certain to offend—or challenge—no one. Many pre-code titles were discontinued, and companies went under. Artists and publishers disappeared from the business, took jobs in commercial art in advertising and mainstream magazines, or found other outlets for their talent, sometimes for the better. Harry Chesler and Victor Fox, whose shops were barely hanging on before the Comics Code went into effect, left the business, content to know that they had cast large shadows in the early days of comics. Charles Biro, whose writing for

Crime Does Not Pay

helped shape the explosion of true-crime comics in the late forties and whose crime fighter, Daredevil, became a tight combination of costumed hero and detective, had seen enough, as had Jack Cole, former Eisner employee, creator of Plastic Man, and contributor to EC’s line of crime comics; Cole, noticed by Hugh Hefner, who was busy creating his own controversial magazine for adult males, would become one of

Playboy

’s most significant early contributors.

Ironically, things improved when the baby boomers, the ones the Comics Code was designed to protect, came of age and challenged the strict standards by producing comics that were bold and relevant, addressing the issues of the times. Underground comic books, preferring to go by the title “comix,” the product of the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll counterculture of the sixties, would gleefully thumb their collective nose at the code.

When these times rolled around, Will Eisner would be ready.

Eisner might have welcomed the opportunity to exchange his ongoing problems with

P

*

S

magazine for a censorship tussle. The magazine had jumped off to a good start, at least in terms of the press runs and continuity, but after appearing six straight months between June and November 1951, production halted completely for the next seven months owing to problems with budgeting and infighting among the staff. Only nine issues would reach GIs over the next twenty-five months. By the summer of 1953,

P

*

S

was in such disarray that its future was in doubt. Seven years later, Eisner would sit down with Paul Fitzgerald, the magazine’s managing editor, and characterize the period with disarming candor. “I have never known personal distress to equal the gloom, doom, despair, frustration, betrayal, and helplessness that enveloped me during that horrible summer of 1953,” he told Fitzgerald.

His troubles had begun much earlier, with the breakdown of his working relationship with Norman Colton. Eisner, stubborn whenever his work was questioned or criticized, found himself locked in personal and professional battles with Colton that left him seething in frustration. Both Eisner and Colton wanted control of the magazine’s direction, and neither was inclined to budge in a disagreement, especially after Eisner rebuffed Colton’s demands for part ownership of the publication. Eisner was accustomed to working to order, to making changes in his work to accommodate the wishes of his customers, but on far too many occasions the dispute in the early years of

P

*

S

struck him as being petty or nitpicky. When he’d served in the army, he’d been a celebrity artist, highly regarded by his Pentagon superiors, who were more apt to defer to his knowledge and background than to set their jaws and demand changes. He’d endured some raw-nerve moments, but they were nothing in comparison with the battles he encountered as a civilian working for the military. Everybody in the army seemed to have something to say about the magazine.

As Eisner—and the army—eventually determined, Colton had issues that explained his behavior. One could have forgiven Colton his ambitions if he hadn’t been so adept at working all sides against the middle for his own benefit. A master of office politics, Colton knew when to schmooze with the right people, how to drop the right piece of information guaranteed to create disputes that would place him in a favorable light, when to brownnose and when to plant his feet, and perhaps most important of all, how to plan for his own advancement. Eisner detested these calculating qualities, but he was living in suburban New York and

P

*

S

was coming out of the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. So as long as he could limit his personal contacts with Colton and the army, he couldn’t have cared less about Colton’s machinations.

Then Colton began making more frequent visits to New York, supposedly to consult with Eisner on the magazine’s content. As it turned out, Colton had other things on his mind. Eisner resisted Colton’s attempts to obtain part ownership in

P

*

S

, growing more uncomfortable with each of Colton’s visits, until one day he answered his door and was greeted by two government agent types, dressed in black suits, demanding some of his time. Eisner insisted that he have an attorney present before he spoke to them, but that turned out to be unnecessary. The men were from the FBI, and they were investigating Colton on allegations that he might have fudged his travel expenses for the army. As if on cue, the phone rang. Eisner answered it and found himself talking to Colton, who wanted to meet him at Grand Central Terminal. The agents followed Eisner to the meeting and confronted Colton. His days at

P

*

S

were over.

The army wasn’t happy with the way things were going at the magazine in any event, and shortly before the end of Norman Colton’s tenure at

P

*

S

, in an effort to restore order to a situation that was spiraling out of control, officials brought in Jacob Hay, a columnist for the

Baltimore Sun

, to work as managing editor. After the departure of Colton, Hay was made acting editor, but he was so shocked by the disorganization at

P

*

S

that he quit his post after two months in September 1953, took a position at the

Greensboro Daily News

, and a short time later wrote a six-part exposé on just how bad things were at the magazine.

This dark period couldn’t have arrived at a more inopportune time for Eisner. He and Ann were expecting their second child, he’d just purchased a new home, and while American Visuals had other clients bringing in income,

P

*

S

was supposed to be his meal ticket. Thirteen years earlier, when he’d gambled and left Eisner & Iger for

The Spirit

, his business and artistic instincts had been rewarded. Now, here he was, working for the government on an army publication being issued during a time of war, a venture that should have been solid enough, but his future looked shaky.

Fortunately for Eisner, the army made an excellent move with its selection of the magazine’s third editor. James Kidd, a thirty-three-year-old veteran of World War II, teaching journalism at West Virginia University when he was offered the job at

P

*

S

, was as different from his predecessors as one could have imagined. Quiet, soft-spoken, straitlaced, and no-nonsense, Kidd brought stability and credibility to the chaos that had been

P

*

S

magazine. Twice decorated for valor during the war, Kidd was an officer and he knew the army, and with his recently earned Master of Arts degree to go with his Bachelor of Science Journalism degree, he knew reporting and editing. Not given to cursing, raising his voice, tossing things around the office, or showing much of any emotion, for that matter, Kidd took a laid-back approach to business that greatly contrasted with the kinetic energy that seemed to bounce off Eisner, yet there was never a question of his authority. Eisner took one look at Kidd and declared, “I don’t think I want to play poker with that guy.”

He would, however, work well with him for the next eighteen years.

The first issue of

P

*

S

magazine under Jim Kidd’s guidance was published in January 1954, and from that date until Eisner left the magazine in 1971, 212 issues were published, with only two delays. Kidd and Eisner disagreed frequently, but Eisner never doubted Kidd’s professionalism or intentions. For his part, Kidd acted as an effective buffer between Eisner and the army brass.

The magazine was a work in progress throughout the Korean War. The format remained the same: a five-by-seven digest-sized magazine, forty-eight pages, with a four-color wraparound cover done by Eisner in comic art, eight color pages of maintenance-focused stories by Eisner in the middle, and the rest devoted to articles, charts, and other graphic material related to preventive maintenance. Shortly after joining

P

*

S

, Kidd hired Paul Fitzgerald, a World War II vet and one of Kidd’s former students at West Virginia University, to work as the magazine’s managing editor. Fitzgerald assisted with the post-Colton office restructuring as well as some of the fine-tuning of the publication’s content.

These were trying times for Eisner, who never adapted easily to change. (“If you moved his socks to another drawer, it was a crisis,” his wife would joke.) He had to adjust to a new staff, hit his monthly deadlines, and deal with an army chain of command that bordered on the preposterous. Every month, Eisner would deliver a dummy of the magazine’s layout, as well as rough pencils of the artwork, which Kidd would subsequently take to the Pentagon for review. From this point until the final proofs were delivered to the printer, there would be discussions over content and artwork, adjustments to editorial content, disputes over details, revisions, more discussion, and enough friction to make all parties involved wonder what the hell they were doing in this business in the first place. Eisner, the only artist in the bunch, fumed whenever others picked apart his work and insisted on changes.

“It would reach a point where Kidd or I would have to say to Will, ‘You’re right, and we know you’re right, and you know that we know, but we can’t do it that way,’” Paul Fitzgerald recalled. “Quite frequently, that would provoke him into coming up with a third alternative.”

Dating back to his

Army Motors

days, Eisner could really find himself at loggerheads with others when they failed to understand or appreciate his original vision of approaching his readers on their level, in their language, in ways that would make the material easy to remember. The military, which devoted so much time and effort to shaping a GI’s thought processes, wasn’t interested in the informal or humorous. Joe Dope and his sidekick, Pvt. Fosgnoff, were perennial points of contention—and, in essence, prime examples of the never-to-be-resolved differences between Eisner and the army. Eisner believed—and correctly, if one could judge by the reader response to

P

*

S

—that these two misfits exemplified, through their failures, how something should

not

be done. Army officials felt otherwise. Joe Dope, they countered, invited ridicule of the training process and, by extension, the army itself. Soldiers might be amused by his foibles, but they were enjoying themselves at the expense of the officers who trained them. In addition, preventive maintenance was a difficult concept to address to begin with, since the military didn’t want it even implied that its equipment was anything but top-notch.

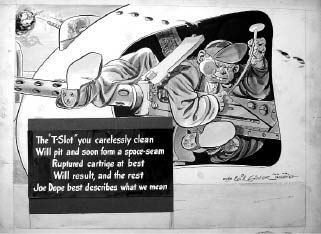

Eisner’s contributions to

P

*

S

magazine convinced him that comics could be used as an educational tool. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

“I was fighting something much more deadly than not being allowed to make fun of an officer,” Eisner told Tom Heintjes in 1990. “I was fighting the huge internal bureaucracy of the military, which wanted to suppress information that would make them look bad. They would blame the soldiers for equipment failures, when in fact it was manufacturing flaws. That’s one of the great villainies of the military, I’ve always thought.”

To back his claim, Eisner mentioned a tank that was designed in such a manner that when a shell was fired, the gun’s recoil would smash the breech into the gunner’s chest, killing him instantly. “When I learned this, I told them the tank was poorly constructed, that it was costing lives because of some stupid engineer. They said, ‘No, you’ve got to train the gunners to sit sideways in the tank,’ even though the seat was designed to look forward! I was furious, but I was powerless.”

The Joe Dope debate crested in 1955, when a memorandum of record laid down the law:

1. Effective immediately the separation from the service of Private Fosgnoff at the convenience of the government and in the best interests of the service;

2. A replacement having a good military bearing and appearance will be developed;

3. The use of, or reference to, the word “dope” as a last name for the character “Joe” will be discontinued and the heading of the continuity will be changed to read “Joe’s Dope”;

4. The appearance of Joe will be altered, including removal of his previously protruding teeth;

5. The appearance of incidental soldier-characters used for humorous and illustrative purposes will be prepared so that humor, where such is called for, will be connoted through the use of expression and attitude, rather than through grotesque distortion.