Will Eisner (3 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

The newspaper job gave Eisner his first lessons in business. There was an all-out competition for the prime selling locations, and the person who won a good spot was usually the biggest and strongest competitor. Billy would set up his stand, only to be chased away by a kid capable of beating the bejabbers out of him. Billy would move to another location until another big kid came around. Eventually, he found a place where he wouldn’t be challenged, a place where by process of elimination he was the biggest kid in the area.

Linoleum block illustration for the

Medallion

, a politically charged

high school magazine. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

Billy wasn’t happy about having to work every day, but he didn’t resent it much, either. He could dismiss any feelings of resentment with the knowledge that his family needed the money. Besides, New York had a lot of newspapers at the time, and all but the

New York Times

published comics, which Billy would read religiously whenever he found some downtime. He’d been reading comic strips for years, but now, with far greater supply, he began to study them more seriously. His favorites included E. C. Segar’s

Thimble Theatre

, George Herriman’s

Krazy Kat

, Alex Raymond’s

Flash Gordon

, and Milton Caniff’s

Terry and the Pirates

. He studied the comics, trying to dissect each artist’s methods. Later, at home, he would try to imitate the style of each in his own sketches, based on what he had learned.

Art was becoming the big priority in Eisner’s life. Using a makeshift drawing table fashioned out of a board angled against a small stack of books, Billy (with plenty of encouragement from Sam Eisner) would draw whatever captured his fancy. There was no doubting his talent or enthusiasm. On occasion, father and son would head to a park and sketch landscapes or take the train to Manhattan and visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they would study the classical painters or, if they managed to eke out the fee, take advantage of the Met’s policy of allowing artists the opportunity to copy the classics in their own sketchbooks or paint them on their own canvases.

Comics artist Nick Cardy, although a few years younger than Eisner, grew up during the Depression years, and he too learned many of his basic sketching and painting skills from sessions at New York’s famous art museum. “We couldn’t afford my going to art school,” he recalled. “What I used to do is go to the library and look at the art books. Then I started walking to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’d go there at certain times of day and they’d put their easels out and paint. I used to look at the paintings. I’d look at the painting at the weakest part of the painting, to see what he painted over. I’d be about a half inch away, trying to find out what the undertone was, of what he did on that. People thought I was crazy.”

High school study: “Man in Russian Cap.” (Will Eisner Collection, the Ohio State

University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Like Cardy, Eisner was either too young or too poor for the better art schools. In a scene depicted in

To the Heart of the Storm

, Sam Eisner scraped together enough money to enroll Billy in a cut-rate art school, located in a run-down old building and hosted by an eccentric teacher who used a strange contraption to teach students to draw. The machine had two arms, one attached to the teacher and the other to the student, and art would be “taught” when the teacher drew: the student had no choice but to let his arm and hand be guided in whatever direction the teacher chose. The teacher promised to make Billy an artist in three weeks; Billy fled the school after one session.

Fannie Eisner watched her son’s growing interest in art with skepticism at first, and later, when his talent was apparent, with increasing alarm. Her husband hadn’t been able to parlay his talents into a decent living, but here he was now, with a nation mired in economic crisis, encouraging his oldest son to chase a dream. And that, to a practical woman like Fannie Eisner, was all that art was: a dream pursued by talented people doomed to fail. Some of the greatest musicians and painters and writers in history had created immortal work and died in poverty. While he was painting scenery for the Yiddish theater, Sam had met such actors as Emanuel Goldenberg and Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund, who would change their names to Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni, respectively, and achieve stardom in the movies. But their successes were rare exceptions. Most of the actors in the theater moved on to other careers or, if they persisted, toiled in anonymity and poverty their entire lives. Fannie firmly believed that Billy would suffer the same fate if he insisted on continuing in art. He’d be much better off financially if he studied to be, say, a teacher. There was always a demand for a teacher’s services.

Billy had no recourse but to hear out everything his parents said—to him or to each other. His mother, he knew, was utterly correct in her pleas for practicality; Billy

was

selling newspapers because his father couldn’t find work as an artist. On the other hand, his father loved his art, and he presented a compelling case for the argument that life, when the final ledger was tallied, was defined more by joy and experience than by numbers in a bankbook or material possessions.

Both arguments made sense. Billy hated to disappoint either of his parents, so he listened again and again to his parents’ ideological tug-of-war, unaware that in less than a decade he’d be having it both ways—the aesthetic and the practical, the seemingly incompatible pair, married into a career that would set him apart from all of his contemporaries and establish him as a model for artists in the future.

Billy’s choice of high schools wound up being a good one. DeWitt Clinton High School, an all-boys’ school located nearby in the Bronx, would become, over time, an incubator for great achievers. Its alumni would include an incredible range of talent: James Baldwin, Arthur Gelb, Paddy Chayefsky, Ralph Lauren, Richard Rodgers, George Cukor, Fats Waller, Burt Lancaster, Avery Fisher, Martin Balsam, Neil Simon, and A. M. Rosenthal focused on the arts; basketball Hall of Famers Dolph Schayes and Tiny Archibald starred on the school’s team; and comics artists Stan Lee, Bob Kane, Bill Finger, and Irwin Hasen walked the school’s halls. And this is only a partial list. Stan Lee would one day joke about how film and television creator, producer, and director Garry Marshall would beam every time he met someone who’d attended his alma mater. “Garry is so proud of the fact that he went to DeWitt Clinton that it’s like the biggest thing in his life,” Lee quipped.

Eisner, now calling himself “Bill”—or, if he was feeling really formal, “Will”—wasted little time in establishing a reputation at the school. Although only a marginal student, he was an excellent artist and writer, much more advanced than his classmates, and he signed on to work on the

Clintonian

, the school’s student paper, for which he did illustrations and a regular comic strip. His first published art for the paper, an illustration for an article entitled “Bronx’s ‘Forgotten’ Ghetto Revealed; ‘Is School for Crime,’ Doctor States,” a drawing of Bronx street vendors operating out of carts and entitled “At the ‘Forgotten’ Ghetto,” appeared on December 8, 1933.

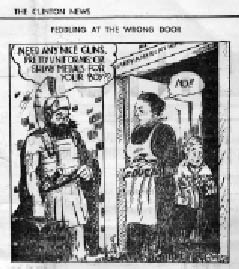

“Peddling at the Wrong Door”: This one-panel cartoon was published in the

Clintonian

, Eisner’s high school newspaper. (Will Eisner Collection, the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Over the course of the next three years, his work seemed to be everywhere. He worked on set designs for Clinton’s “Class-Nite” variety show, designed posters for the school, appeared in

Magpie

, Clinton’s literary magazine, and, with classmate Ken Ginniger, started an independent literary magazine, the

Hound and the Horn

. When Ginniger ran for class president, Eisner designed his campaign posters. The workload wasn’t just a matter of beginning a portfolio; each assignment or activity exposed him to new areas of art, from cartooning to art deco to commercial design, giving him remarkable range for someone so young. Clinton couldn’t afford expensive metal plates for its publications’ illustrations, so Eisner learned to make cuttings out of wood and linoleum. Later, while still in high school, he took a job at a Manhattan printing company, where he learned the ins and outs of printing presses.

“Clinton Commerce”: A woodcut appearing in the November 9, 1934 issue of the

Clintonian

. (Will Eisner Collection, the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Even as a high school student, Eisner was extremely curious, with a capability of seeing, grasping, and retaining large volumes of information. He aspired to be a syndicated cartoonist—“[it] represented a way out of the ghetto,” he’d explain later, adding that this was his “primary motivation”—but after working on the drama projects, including the variety show, which was written by fellow student Adolph “Singin’ in the Rain” Green, Eisner seriously contemplated following in his father’s footsteps and working as a stage designer. As Eisner would recall, George Dunkel, a fellow student and the son of the designer of the Metropolitan Opera’s scenery, mentioned that he could find them work with his father on road productions—a proposal that Eisner found enticing. Predictably, Fannie Eisner opposed the job, which would have taken her son away from home for extended periods and exposed him to all the wrong types of people.

“She had an aunt or a sister who was a showgirl,” Eisner remarked, “and this would lead to all kinds of terrible things for her boy. And, not only that, but I had to stay around and make some money. So that fell apart.”

“My mother stepped in and put a stop to it,” he said on another occasion, “because, she said, ‘that kind of life, actors were nothing but bums and the women were trash, and if you get involved in that, you’re going to be ruined.’ She would hope I’d get a nice, honest job.”

This setback was nothing in comparison with the clash that Eisner had with his mother when, while still a high school student, he attended classes at the prestigious Art Students League of New York—an institution that gave starts to such artists as Georgia O’Keeffe, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jackson Pollock. The school boasted a supremely gifted staff, and Eisner studied under George Bridgman and Robert Brackman, two of the finest teaching artists of their day.