Will Eisner (35 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Ann was insistent, Will relented, and in the summer of 1983, they began the process of finding a place in Florida and packing up their belongings. They moved on July 1, but it wasn’t easy. Eisner was a pack rat who kept every scrap of paper he’d ever drawn on, every letter he’d ever written or received, every book he’d ever read. His personal archives included original art, tear sheets, published books, magazines and comics in which his work (or interviews) had appeared, newspaper clippings, awards, memorabilia, and business correspondence. The long-distance move simply would not permit the transfer of all this from one place to another.

Fortunately, largely through the efforts of Cat Yronwode, there was now an order to Eisner’s archives. A lifetime’s work had been organized and cataloged. Some of the memorabilia could be sold off to collectors. The rest of the archives would be divided between Eisner’s new home and a university library. Yronwide contacted Ohio State University, which housed the Milton Caniff collection, and the university’s Library for Communication and Graphic Arts agreed to add the Eisner papers to a collection that already included extensive holdings of editorial cartoonists, the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, and art by magazine illustrators.

For the library, obtaining the Eisner collection was a major event, adding to its reputation of being one of the finest cartoon archives in the academic community. “Eisner’s work has been of major importance in the development of both comic book art and narrative,” Lucy Caswell, the library’s curator, declared when the university formally announced its procurement of the Eisner collection. “His creative use of layout and design in the 1940s influenced a generation of cartoonists.”

One unexpected offshoot of the Eisners’ move to Florida was a new, twenty-eight-page graphic story, “A Sunset in Sunshine City,” published in

Will Eisner’s Quarterly #6

and reprinted later in the miscellany

Will Eisner Reader

. It is the story of Henry Klop, widower, father of two daughters, and owner of a well-respected small business, who has bought a retirement condominium in Florida. It’s a bittersweet move. As he wanders down the snowy streets of New York, Henry is haunted by the memories of his youth, marriage, children, and business—all preserved, it seems, by the mundane objects of the city itself. “After all, what else is there to bear witness to the past?” he wonders, repeating an Eisner theme explored in

New York: The Big City

. “Only lampposts, fire hydrants … a street, a sewer, a building … They are monuments to my memories.”

“That was his getting used to things,” Ann Eisner said of “A Sunset in Sunshine City.” Like Henry Klop, Eisner couldn’t imagine himself as a retiree so far removed from the memories of his youth—a point that Ann Eisner readily acknowledged. “It’s mostly retirees in south Florida where we moved,” she said, “and it took some getting used to.”

Ironically, Ann made a significant contribution to the story when she suggested the montage of Henry Klop’s New York memories presented early in the story. Ann’s involvement with her husband’s work had developed slowly over the years: from the earliest days of their relationship, when she had no use for comics and didn’t even visit his office until after they were married, to her much greater interest and more active involvement in his art after he began his graphic novels.

Denis Kitchen watched this evolution from the perspective of a publisher. On one occasion, shortly after he and Eisner began working together on

The Spirit Magazine

, he visited the Eisner home in White Plains. During a lull in their dinner conversation, he asked Ann, innocently enough, to name her favorite

Spirit

story.

“There was a silence,” Kitchen remembered, “and she kind of glanced at Will, and then looked at me and said, ‘Well, honestly, I’ve never read any of them.’ My jaw dropped. As a fanboy and a guy making a living publishing this stuff, that was incomprehensible to me. I think she saw my response and felt slightly embarrassed. She said, ‘I married the man, not the cartoonist’—which I thought was a great comeback. I didn’t bring it up again.”

Eisner valued his wife’s feedback. Although they had very different tastes in entertainment—he favored public television, she network programming, for instance—she was well-read and had strong instincts on what might work or be appropriate in a story, and she wasn’t shy about stating her opinions. She strongly objected to one scene in

Signal from Space

, which depicted one of the characters urinating in a rainstorm. (“Will, that’s not you,” she scolded. “You shouldn’t do that.”) On another occasion, she protested her husband’s intention of putting together a never-to-be-released Poorhouse Press book entitled

30 Days to a New Beautiful You

(or, in its original working title,

30 Days to a Brick Shithouse Figure

).

“He wanted her opinion,” Denis Kitchen said. “I can remember one time when Will had a character having an affair in the story, and Ann proofread it and said, ‘This isn’t plausible. The wife would know he was having an affair.’ Will said, ‘How?’ and Ann said, ‘The woman would just know.’ Will respected Ann’s opinion enough that he rewrote the scene.”

The Eisners impressed their friends as an ideal couple. Even after thirty-plus years of marriage, they were playful, openly affectionate, clearly still very much in love. Every year on their anniversary, Will would tease Ann about signing on for “one more year,” and on those occasions when Will would bring home flowers, Ann would tease him about what he must have done wrong to warrant the purchase of such an unexpected gift. As extensive as his business travels had been, Will still missed Ann when he was away, and after she retired and they moved to Florida, Ann would accompany him on almost all of his journeys. Ann enjoyed watching her husband bask in his popularity at comics conventions and lectures, yet she had a way of seeing that none of it went to his head.

“To me, they were the role model of a married couple,” noted Denis Kitchen. “I saw them in their natural environment, where you can only fake things so long. I would especially notice it in the morning, at breakfast, or at dinner. Will was obviously the famous one, but at home he was just Will. He’d leave his ego at the door, and Ann would reprimand him if he would even say anything that seemed a little pompous. It was a complete give-and-take.”

Jackie Estrada, a longtime volunteer and administrator of the San Diego Comic-Con, the largest annual comic book convention in the world, had many occasions to see the Eisners together. She and her husband, cartoonist and former Eisner student Batton Lash, traditionally had breakfast with the Eisners on the Friday morning of the convention, when the four of them could relax before going off to face the bedlam on the convention floor.

“It was so funny when Will and Ann were together,” Estrada said. “Will would start to tell a story, and Ann would go, ‘That’s not the way it went at all. That’s not what happened.’ And Will would go, ‘I’m giving her one more year.’ They were a great match.”

Ann Eisner’s biggest concern about their move to Florida was the effect it would have on her husband when he could no longer teach. But those worries were put to rest when Eisner told the School of Visual Arts that he was moving and submitted his resignation. The school officials, shocked to be losing one of their high-profile teachers, countered with an offer to fly Eisner to New York every other week for classes. Eisner accepted. Those forays to the city, along with a couple of other longer visits, gave Will the “carbon monoxide fix” he needed to keep his yearnings for the big city at bay.

Eisner found an office near their home and set up shop. It had two rooms—an outer office and a studio in which to work—and was located in a small professional building in a strip mall. Eisner found himself surrounded by doctors, dentists, lawyers, and accountants—hardly the environment he’d enjoyed in New York City or in his studio in White Plains, but it was functional.

He already had a couple of projects in mind that he wanted to develop: an autobiographical work and a textbook on sequential art. Neither approached

A Life Force

in ambition, but both reflected his nostalgia for his lost youth and the city he’d left behind.

The Dreamer

, a roman à clef of his early days in comics, started out at approximately the same length as “A Sunset in Sunrise City,” but Denis Kitchen and Dave Schreiner were so taken by it that they pressed him into extending it to include more detail and anecdotes.

“Dave Schreiner and I both were badgering him, urging him to put more flesh on the bone,” Kitchen recalled. “We were fascinated with early comic book history, and we had been asking him to do kind of a memoir in comics form. When he did that, I said to him, ‘Will, this is a great outline, but we want the whole story.’ And he very reluctantly said, ‘All right, all right, I’ll add eight pages.’ He would, and we’d say, ‘More.’ We pushed him and pushed him until it got to around fifty pages, and then he said, ‘That’s it. That’s it.’ We could tell it was an emphatic one, so we said, ‘All right, all right, fine.’

The idea for

The Dreamer

originated at the School of Visual Arts. His young student artists were all dreamers hoping to use their talents in one way or another to earn a living, but soon enough, they learned that there was quite a gulf between dreams and reality.

“At the end of the semester, students were always wringing their hands over having to get out into the field,” Eisner stated. “What would happen to them? Where were they going to go? And I thought, Gee, let me tell you my story. It’s to say to the kids who are growing up and going out into the field, ‘Look, it’s always been this way and if you stay with it, and remain the dreamer that you really are, you’ll prevail.’”

The Dreamer

started out as a fictional tale, with Billy Eyron, the main character, stepping into a cafeteria and meeting a fortune-teller who offers to tell his fortune for a dime. It’s New York City, 1937, and like the young, post-Depression Will Eisner, Billy is lugging around a portfolio, hoping to find work. Billy laughs off the fortune-teller’s predictions of success, but he later stops at a fortune-telling machine on the street. Its message, too, is that he will be a success in his chosen career.

Eisner shifted at this point to his actual experiences in comics, using the real people and events. He reasoned that nonfiction was better than anything he could have invented; plus, in relating his experiences, he was giving the history of comics—or at least his part of it. Readers were introduced to such players of the Golden Age as Jerry Iger, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, Harry Donenfeld, M. C. Gaines, Victor Fox, and Busy Arnold, as well as to such up-and-coming artists as Bob Kane, Lou Fine, Bob Powell, Jack Kirby, George Tuska, and others in the Eisner & Iger shop. Eisner discreetly changed their names, but to anyone familiar with comics, the name changes were more the source of a humorous “name the character” game than a way of disguising identities. Jack Kirby became “Jack King” in homage to Kirby’s “King of Comics” nickname; Lou Fine became “Lou Sharp.” Even the comics and their characters were given fictitious names:

Superman

translated to

Bighero: Man of Iron

, while

Batman

became

Rodent Man

. For Eisner, it was a playful exercise and a way to avoid potential litigation, but for aficionados like Dave Schreiner and Denis Kitchen, who were eager to see history played out in graphic form, it was a source of consternation.

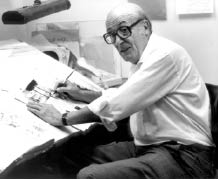

At the drawing board, 1985. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

“We were so frustrated that he didn’t just call people who they were,” Kitchen complained. “I remember saying to him, ‘Why must you disguise those people?’ He said, ‘Well, some of them are still alive, and I don’t want to embarrass them or their families.’ It was the gentleman in Will. And part of it was there was a clear implication that Donenfeld and Liebowitz, the guys who ran the early DC Comics, were crooks. I said, ‘Will, everybody knows those guys were crooks. What’s the problem?’ He said, ‘I don’t know firsthand that they were crooks.’ I said, ‘Well, is there anyone still around who even knows

second

hand?’ He laughed but said, ‘No, I’m not going there. This is the way I want to do it.’ I wanted to have some annotations early on, but he said, ‘No, no. Let people figure it out. That’s part of the fun.’”

Eisner crafted his book in tight, compact episodes. He included the major moments of his development as a comics artist, including his early work with

Wow, What a Magazine

!, the formation of the Eisner & Iger studio, the

Wonder Man

fiasco with Victor Fox, and his initial meeting with Busy Arnold and Henry Martin. Colorful episodes such as Jack Kirby’s confrontation with the Mafia thug, George Tuska punching Bob Powell, and even Eisner’s brief fling with Toni Blum spiced the narrative. Through it all, Eisner never lost sight of his “dreamer” motif. The comic book world was a place where dreamers came face-to-face with ne’er-do-wells, crooks, grifters, and hungry businessmen, all looking to make a name and a buck, regardless of the compromises they had to make. At the end of the forty-six-page story, with World War II looming in the not-so-distant future, Billy again drops a coin in a fortune-telling machine. The message is the same: He will be a success in his chosen profession.