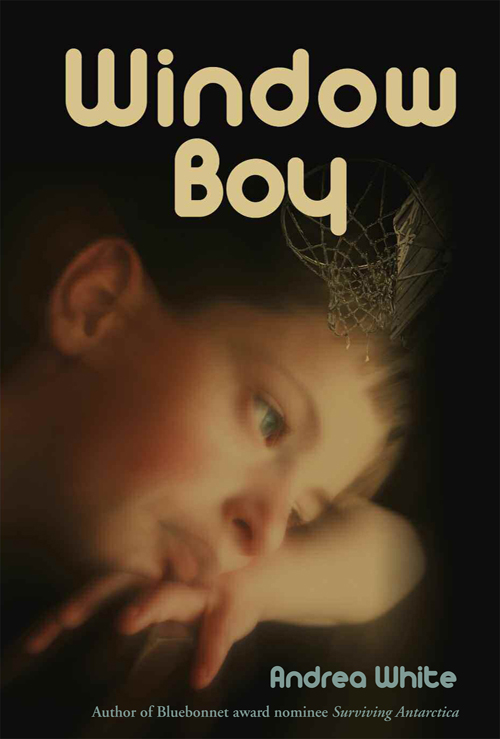

Window Boy

bright sky press

2365 Rice Blvd., Suite 202 Houston, Texas 77005

Box 416, Albany, Texas 76430

Text copyright ©2008 Andrea White

“The Lessons of Classroom 506,”

The New York Times

. September 12, 2004 ©Lisa Belkin

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means,

including information storage and retrieval devices or systems, without prior written permission

from the publisher, except that brief passages may be quoted for reviews.

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data

White, Andrea, 1953-

Window boy / by Andrea White.

p. cm.

Summary: After his mother finally convinces the principal of Greenfield Junior High to admit him,

twelve-year-old Sam arrives for his first day of school, along with his imaginary friend Winston Churchill,

who encourages him to persevere with his cerebral palsy.

ISBN 978-1-9339779-14-4 (jacketed hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Churchill, Winston, Sir, 1874-1965–Juvenile fiction. [1. Churchill, Winston, Sir, 1874-1965–Fiction.

2. Cerebral palsy–Fiction. 3. People with disabilities–Fiction. 4. Imaginary playmates–Fiction.

5. First day of school–Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.W58177Wi 2008

[Fic] – dc22

2008000492

Book and cover design by Cregan Design,

Ellen Peeples Cregan and Marla Garcia

Edited by Lucy Herring Chambers and Nora Krisch Shire

Printed in China through Asia Pacific Offset

Andrea White

To my friend, Maconda, on the occasion of her birthday,

With special appreciation to

Franci Crane, Elena Marks, Sis Johnson and Michael Zilkha,

And with gratitude to Lisa Belkin for her inspirational article.

“We’re all worms, but I do believe I am a glowworm.”

-Winston Churchill

Contents

Chapter 1

As always, Sam Davis, age 12, is staring out his window. It’s a double-sided picture window, shaped like a basketball court: rectangular, with a line down the middle. The blue drapes are pushed to one side, leaving him a clear view of Stirling Junior High.

If it weren’t for the rutted field between them, Stirling Junior High would be in Sam’s backyard. The school, a flat building, stands adjacent to a concrete playground with a metal roof and an outdoor basketball court. In his eagerness to get as close as he can to the court—and to basketball, the best game in the whole world—Sam is resting his forehead against the glass.

When he sneezes, Sam’s head rears back. His wheelchair slips forward, and he bangs his head against the glass.

“Sam, don’t lean on the window.”

His caretaker’s footsteps sound behind him, and Miss Perkins takes his hand. She claims that she’s an “older young woman,” and when Sam looks at her, he thinks: it’s true. Her gray hair and white nurse’s shoes are old, while her clear eyes, strong body and unlined skin are young.

Sam and Miss Perkins are alone again tonight. Sam’s mother is eating at her favorite Italian restaurant: Fred’s. Although Sam would like to go, he’s never been to Fred’s. Too many stairs. He has to content himself with the long skinny breadsticks that his mother brings home.

“Are you ready for bed, Sam?” Miss Perkins asks.

Sam could speak if he weren’t feeling lazy. Instead, he looks down with his eyes. This means no.

“O.K.,” Miss Perkins says. “Do you want me to read to you?”

Sam looks up: yes.

“I got a new book from the library about Dwight D. Eisenhower. Do you want to try it or keep reading about Winnie?” Miss Perkins asks.

“WWWWiinnnie,” Sam says. Winnie is their nickname for Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill.

Miss Perkins’ tread is light as she walks away. When she returns, Sam knows she will be carrying a medium-sized, blue book:

My Early Life

by Winston Churchill.

When Miss Perkins first started reading about Winston Churchill, Sam felt resentful. Sam thought he was just an old man with baby-pink skin who liked cigars. The Prime Minister of England, the man who fought Hitler during World War II—what did Winston Churchill have to do with him? But as his caretaker read about the boy Winston Churchill, Sam began to listen.

Young Winston Churchill was inventive; he built elaborate forts. He was brave; once Winston jumped off a bridge and fell thirty feet. He was also mischievous. At school, angry at being scolded, Winston kicked, stomped and tore his headmaster’s straw hat into pieces. Sam doesn’t know what a bad fall feels like, but he understands how it feels to be angry. And he used to have temper tantrums all the time. There is just so much other people don’t understand.

One night, as Miss Perkins’ soft English voice was rolling over him, putting him to bed, her words took on a quality almost as if Winston himself were calling him through time—speaking directly to Sam.

When Miss Perkins put down the book, Sam thought about the fact that Winston Churchill, a great orator, had stuttered as a boy. Since Sam didn’t talk well either, he was curious. In his mind, he asked:

How?

To Sam’s surprise, Winston Churchill answered,

I practiced, old chap.

That’s when Sam learned something very important. Although the voice was in his own head, he didn’t know what the voice was going to say next. The voice was like a friend.

As Sam waits for Miss Perkins to return with the book, he keeps his eyes fixed on the basketball court, hoping. Just past the circle of light thrown out by the crooked lamp post, there in the shadows, he spots movement. Often, a boy named Mickey— Mickey Kotov—comes out on the court at night, always alone.

Suddenly, Mickey dribbles the ball into the light. Mickey is small. Maybe as small as Sam, although Sam looks smaller, crumpled in his wheelchair. Watching Mickey run around the court so fast, Sam wishes again that when his brain got damaged as he was being born, his legs hadn’t become useless sticks. It’s O.K. that talking is difficult for him. But basketball players need to run.

Sam has a secret. He dreams of playing basketball exactly like Mickey. But he wouldn’t want Mickey’s life. Sitting at the open window this past summer, he’s learned more about Mickey than his name. Mickey has a father who screams at him.

“Mickey, stop hiding. Come hooome.”

“Mickey Kotov, yoour’e the vorst boy that God ever made.”

“Mickey, I need your help with the plumving.”

Mickey jumps, and a ball arcs against the dark sky. The window is shut tonight, but it doesn’t matter. In his mind, Sam hears the whoosh of the basket. He wants to yell for Mickey. To cheer, “Yeah. Good basket.” But Miss Perkins settles into the chair next to him and interrupts his daydream.

“Anywhere?” Miss Perkins asks.

“Surre,” Sam says.

When Miss Perkins opens the book and begins with the story of Winnie failing another exam at school, her voice is confident and strong, but Sam is too excited to listen.