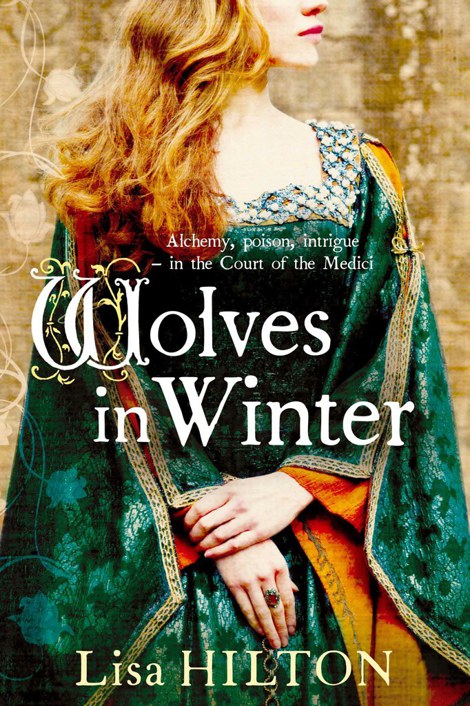

Wolves in Winter

Authors: Lisa Hilton

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2012 by Corvus,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Lisa Hilton, 2012

The moral right of Lisa Hilton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual

persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 84887 467 1

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 709 1

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

To Dominique de Basterrechea, with love

CONTENTS

PART ONE: FLORENCE – 1492–1496

PROLOGUE

Florence, January

1494

T

HE CITIZENS OF FLORENCE, FAMOUSLY, HAVE LITTLE USE

for light. In this city of white and black, grey and dun and

bronze, only the snowy mountain hump of the Duomo, Our Lady of the Flowers, surprises with the gaiety of a meadow, its pink and green façade startling as the sudden space which surrounds it,

opening as it does from the twined, skinny streets surrounding the Mercato Vecchio, where the grim walled houses hunch towards one another as though to protect their inhabitants from glimpses of

the sky, which might distract from the business of getting. Light is for painters, or wastrels; any tremulous sunbeam which steals a cautious finger between the stones is transmuted into gold,

battened down and locked away in chests of iron from the Elba mines. Stingy, envious, proud Florence, its miserly flesh throbbing with the hidden gleam of money.

This night, the city is dark as the black ice which paralyses the river Arno from the Ponte Vecchio along the Bardi embankment. Many years since Florence knew such a winter, so vicious that even

the ice-rimed statues seem pinched and emaciated, huddling into the wind that thrashes the snow of the Apennines through the streets, turning the patient saints of the churches to shivering

goblins. With the winds come the wolves. Keen, running low, they slip like daggers through the white hills of Fiesole. When the farmers force open their doors to the meagre daylight, their lungs

smarting after a night of woodsmoke, they find scarlet mosaics in the snow and cross themselves and close the shutters more tightly, for the wolves are moving. Florence may be a citadel of science,

but it is also a city of prophets, where temples to near-forgotten gods lie beneath the busy feet of the merchants. On the night of Il Magnifico’s death, a she-wolf howled for hours beneath

the city walls. The wolves are moving, and they will bring death with them, from beyond the Alps.

So this night, the streets are empty except for the tiny clatter of dewclaws on the stones of Piazza Santa Maria Novella. Even the beggars who bundle themselves in the wretched shelter of the

portico are hidden. Tap, tap. The wolf pauses on the corner of the Via degli Strozzi, turns, a fluid shadow, and begins to trot northward, toward the Baptistery, where the great pool in which all

the children of the city are given to God is still as lead. Her tail feathers the great carved doors. The gelid marble of the Duomo picks out amber eyes. Audacious, starving, the wolf crosses

straight through the piazza, no shadow now, lengthening her stride until she bounds in black flashes of sinew and need, past the chapel of San Lorenzo and into the Via Larga, her skull aflame with

the scents of boiled meat, of peppered lard and spiced pigeon, cured pork and creamed chicken, carried from the kitchens and larders of the Palazzo Medici. Saliva hisses on the snow as she noses

frantically along the street doors, but this is Florence, and they are iron bolted.

The wolf feels the suck of her empty belly beneath her ribs, lets out a miserable whine, shoves and gnaws, but the doors hold fast. Her black pelt ripples with clutches of want. In the wall

beside the doors is a small window, an ingress for messages or alms. The wolf rears her body upwards, stretching her length until her paws rest on the sill. The wooden shutters are loose, their

hinges weakened with the contractions of the long winter. The wolf drops to the tamped snow, circles back, gathers the force of the wind in her shoulders, leaps. Her snout strikes the wood, the

shutters make a flat thud on the soft drift inside, she scrabbles for purchase, hindlegs and tail beating the air, hauls her bruised weight through the aperture, lands noiselessly, buried. She is

inside.

The

cortile

is full of eyes. In Florence, they say that spirits can be imprisoned in statues. In the centre of the courtyard, where the cleared snow shows prints already molten with the

new fall, stands a boy; improbably naked save for gaiters, boots and a teasingly pointed cap, his left hand easy on the plump adolescent curve of his hip, his right resting on the hilt of his

lowered sword. The wolf checks, he is no threat. A little aside is another figure, not a smooth bronze, but a towering, lumpen creature of snow, planed crystal wings soaring from his back, torso

strained about the great serpent which writhes at his feet, jaws agape to strike at him. Already, the lines of the statue are drooping, aged by freeze and thaw. The wolf pays him no mind. The still

air hums with scents, but she does not make her way through the loggia to the service quarters on the ground floor, but, head down, confused by her waning need, she follows another trail, which

speaks to her blood. Tap, tap. Her claws scratch the fine wood of the staircase, mounting and turning, she moves supple as the lathe, one flight, two. Eager now, along a passage, the glands in her

jaw working, wetting the air with her panting, her snout finds a door, pushes slowly until she insinuates herself, drawn by wraiths of desire, into the room.

The room contains a chest, a simple wooden chair, a low truckle bed. Roughly plastered walls, no fire or stove, just a squat iron brazier, its few coals barely disturbing the currents of her

breath. On the bed is a child, a little girl. Or not so little, maybe, a spiky starveling thing. She wears a tattered red dress, once luminous silk dulled and shabby, battered knees and soft,

narrow little arms protruding. Her spine is held erect, leaving a space between her fragile body and the damp wall. Pale hair, colourless as new straw, obscures her face, which is bent forward over

a doll, a stump of a thing, lovemangled, caressed to a grubby chunk of body and a precarious flannel head. The child knows the wolf is there. The wolf hears the stirring of the translucent hairs on

her body, the quickening in her lungs, the deepened grasp of her fingers in the puffy cloth. The muscles above the wolf’s hindquarters contract, readying her to spring, ears flattening she

releases a low growl from the base of her throat.

And the child looks up. Her copper skin catches the flame of the wolf’s eyes, drawing them to her face. Eyes green as the depths of the glaciers high in the Apennine peaks, green and

unfaltering as the ice that even the August sun cannot move. The wolf cannot find the fear cooling on her skin. Her eyes fix the wolf’s eyes, she makes the slightest shake of her head. The

wolf shudders along the length of her black body, stilled as quickly as if she had a huntsman’s arrow in her heart. She whines faintly. Every nerve in her, drained by days of running, ribs

beamed with hunger, wills her to take, to plunge and kill, but she cannot. Head raised, throat exposed, obeisant, she dips her forelegs and shuffles across the boards towards the child. For a

moment, gold light melds with green. Then, silently, she turns and trots for the door.

The child waits, her knees drawn up under her chin, wrapped in her thin arms. She sends her ears out from the palazzo, out into the streets of Florence, over the river and up into the hills,

until she finds the wolf’s heart – and travels with it across the snow at killing speed, bounds longer than her own body, until it slows, slows.

She hears it then, the first quavering howl, and draws back to herself as it is answered, first one, then another and another, the wolves keening for her until the city is encircled with the

baying, riding to her over the darkness, and the child draws her quilt about her, and smiles, and sleeps.

PART ONE

1492–1496

CHAPTER ONE

A

LONG WITH EVERYTHING ELSE, THEY TOOK MY

name. When I came to the palazzo they washed me in a brass tub in the kitchen, as

though I was a fine lady’s pet monkey to be picked over for fleas. I would not speak to them, so they turned out my red dress to look for any signs of me. My mother had sewn it for me, cut

down from her own wedding gown. It was the finest tabby silk, pomegranate-coloured, so when it turned in the light it was sometimes the rich crimson pink of a sunset, sometimes as bright and crisp

as the skin of an orange. The silk came from Kashmir, my papa told me, a mountain place like our city of Toledo, only the mountains were so high only God could see their peaks. My mother stitched

her love into every delicately worked gather on the bodice and sleeves. Inside, where my heart would be, she placed a pentagram, and inside that she stitched my name.

Mura

. From the old

language, when the caliphs were kings in Toledo. Mura: wish, desire.

They saw my mother’s mark, but they could not read it, for it was

aljamiado

, their letters in our first tongue. I can speak Spanish and Arabic and even a little Latin, but I had no

words in theirs yet, and I should not have used them if I had. All my words were kept for curses. Mura, my mother stitched, for I was her wish. But I was no longer Mura Benito, the

bookseller’s child from Toledo. I was

esclava

. Slave. They took away my doll and my red dress and gave me a coarse grey robe, stuffed my feet into heavy wooden clogs. They clipped my

hair close to my head and took it away in a kerchief, to sell for a vanity. My brow bound in a black striped linen cloth, I kept my eyes to the ground and became invisible, just another moving cog

in the machine of the palazzo. I had learned by then that my face brought trouble. I became

Mora

, Moor, because I am Spanish and they knew no better, even though my skin is not plum-black

but the colour of new gold.