Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos (16 page)

Read Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos Online

Authors: Christine Halsall

Subaltern Margaret Hodgson was one of the first ATS officers to be employed as a PI and she joined ‘B’ Section in 1943, along with Subaltern Bridget Bateman. They had attended army PI courses at the School of Military Intelligence in Matlock, Derbyshire. In common with the WRNS, ATS officers who were PIs at Medmenham were few in number. ATS NCOs who had trained as draughtswomen were posted into Medmenham in the last year of the war. Sergeants Joan ‘Panda’ Carter, who had reluctantly found herself as a clerk in the Pay Corps, and Barbara Rugg, who had worked in the Drawing Office at Larkhill, achieved their wish and went to be trained as topographical draughtswomen at Wynstay Hall, Ruabon, North Wales. The three-month course, attended by Royal Engineers and ATS, included map drawing, use of a stereoscope, contouring, plotting and learning how to survey with a theodolite.

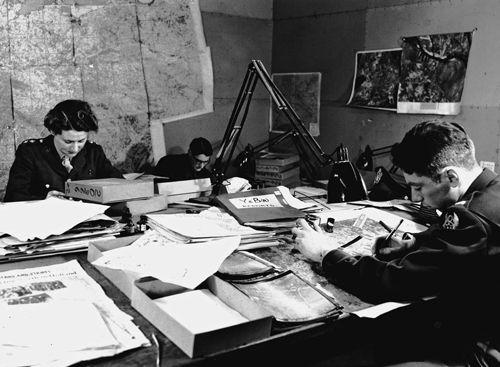

Margaret Hodgson, ATS, at work in the Army Section with a USAAF officer.

‘Panda’ was then posted to the military survey establishment at Esher, in Surrey, to use her cartographical skills:

We were put to work on revising maps using aerial photography and photo mosaics to form a comprehensive picture of bombed areas. The Ordnance Survey maps of Europe at the time were about twenty years old and a way had to be found to bring them up-to-date as quickly as possible. It was very exciting to be working on a map and suddenly see a photograph of a town not there twenty years ago or an autobahn cutting across the country.

17

Barbara became a plotter on army-related photography flown from RAF Benson:

We actually worked at Ewelme in a lovely old house. We had huts in the garden as well and there was a lovely yew tree in the garden. When it was hot weather we would go outside and have our breaks sitting under the tree. We worked long hours and when we came off a night shift we would go to have breakfast in the little café nearby and then cycle straight to the river and row up to Shillingford Bridge, under the bridge and then back.

18

As more and more men were posted away from Medmenham to mainland Europe, to serve as PIs in support of the advancing Allied forces following the Normandy invasion in 1944, women took over their work. The Royal Engineers Drawing Office at Medmenham was originally composed of men only, but became an entirely ATS section when further demands were made for men to go overseas. It was officially noted that there was nothing to show that the work of the ATS was in any way inferior to the Engineers.

Notes

1

. Starling, Jean, Australian War Memorial REL36872.001.

2

. Operational Record Book, Air 28/384, TNA.

3

. Cussons (

née

Byron), Diana, RAF Historical Society seminar.

4

. Smith, Nigel,

Tirpitz: The Halifax Raids

(Air Research Publications, 1994).

5

. Bulmer (

née

Dudding), Pamela, audio recording for the Medmenham Collection.

6

. Churchill, Sarah,

Keep on Dancing

, p.60.

7

. Grierson, Mary, audio recording for the Medmenham Collection, 2001.

8

. McLeod, Norman, ‘History of ACIU’,

unpublished, 1945 onwards, Medmenham Collection.

9

. Kamphuis, Lillian,

Pensacola News Journal

, 11 September 2007.

10

. Kamphuis, Lillian, Medmenham Club newsletters, spring 1995, autumn 1999, spring 2002.

11

. ‘Medmenham USA’, unpublished account, 18 July 1945 (Medmenham Collection).

12

. Grierson, Mary, part of a poem from her personal wartime scrapbook (Medmenham Collection).

13

. Skappel (

née

Campbell), Betty, recorded memoirs, 2011.

14

. IWM 12598 04/2/1 The papers of Lieutenant Geoffrey Price RNVR, held by the Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum. The author was unable to locate the copyright holder.

15

. Espenhahn (

née

Winmill), Mary, audio recording for the Medmenham Collection, 2001, and in conversation with author, 2005.

16

. Churchill, Sarah,

Keep on Dancing

, p.61.

17

. Carter, Joan, IWM papers.

18

. Mottershead, Barbara, recorded memoirs.

FF

D

UTY

After the move to Medmenham in 1941, Danesfield House itself was used for a short time as both working and living accommodation, and in common with many other country mansions it was reputed to have a resident ghost. A clerk typist, newly posted into Medmenham, whom we know only as ‘Jane’, was told the legend of the Grey Lady of Danesfield. The tale, doubtless embellished for each new WAAF’s arrival, was of a nursemaid who, in times past, had claimed to hear footsteps ascending the stairs when the moon was shining and the house silent. The story was playing on Jane’s mind as she groped her lonely way around the house at dead of night to a room set aside for the official ‘hour in bed’, halfway through her first 12-hour night shift:

I ascended the wide staircase to a room four storeys up in pitch darkness. The moon shone through a high circular window on to a mattress bearing rough blankets but no sheets. The calls of owls and sheep came very clearly and I was terrified by the scurry of what could have been a mouse. A bat flapped against the leaded window and a giant moth fluttered helplessly about the moonlit room. When I heard footsteps in the corridor outside I grabbed my skirt and hurried for dear life back to the happy tap of the typewriters in the typing pool.

1

Accommodation was found for some women in local houses. Pat Donald and three other WAAFs were billeted in Wittington Hall, the house next door to Danesfield, where they lived comfortably in the attics:

The house belonged to a Canadian named Garfield Weston who owned many food companies, including Fortnum and Mason. He and his wife had a large family so there were always lots of children around. They were very kind and made cocoa for us when we returned at the end of a 12-hour shift.

2

Susan Bendon commented:

Medmenham is in one of the most beautiful parts of the Chilterns and I was billeted in a dream-like mill house about a mile down a steep hill towards Marlow. The mill was active and was owned by an enchanting elderly couple who seemed to have stepped out of the nineteenth century. In spite of having eleven children, they always addressed each other as Mr or Mrs Broomfield. The PI course was fascinating, with a great atmosphere of camaraderie, there were wonderful pubs all around and it was sheer heaven.

3

The RAF soon requisitioned another large Thameside building to serve temporarily as the WAAF officers’ mess until sufficient huts were built in the grounds of Danesfield House. Phyllis Court was an Italianate-style house built in 1837 close to the centre of Henley, with beautiful gardens overlooking the finish line of Henley Royal Regatta. Some WAAFs lived and ate there, others came from their billets just for meals; buses then transported them to and from RAF Medmenham. Hazel Furney was billeted with a friend in a charming beamed cottage opposite the Angel Inn by the bridge in Henley-on-Thames, where they enjoyed living in a homely atmosphere. They would often punt home from Phyllis Court to Henley after dinner and struggle back with it to have breakfast the following morning.

Section Officer Lady Charlotte Bonham Carter, known at Medmenham simply as ‘Charlotte’, lived in the mess. She was older than most WAAFs, having served in the First World War with the Foreign Office. Just before war was declared in 1939 she trained for Air Defence and took a flying course, commenting that she missed not having a motor horn when up in the air. She subsequently joined the WAAF at the age of 47 and served initially as an instrument mechanic before being commissioned in 1941 and posted to RAF Medmenham after PI training.

4

She was an efficient officer, remembered with great affection by many former colleagues, for her kindness and her eccentric, unmilitary behaviour. Charlotte always carried an umbrella and a basket or string bag containing food, as she was permanently hungry, even taking a basket of sandwiches on a church parade. She made up marmalade sandwiches at breakfast time in Phyllis Court and tucked them into the envelopes that her post had been delivered in earlier, making it easier to transport them to work on the bus. Thus they were always handy should hunger suddenly strike. She was once detached from Medmenham for a few weeks, and her section gradually developed a smell that increased in pungency. Following a search, a packet of marmalade sandwiches, covered in green mould, was discovered tucked into a filing cabinet.

Rows of huts sprouted up in the gardens surrounding Danesfield House throughout 1941 and these provided living quarters for men and women and all the messes, leaving the house itself to accommodate many working PI sections. ‘Jane’ wrote:

November 1941 was bitter. Water in the fire buckets froze, the walls in the huts (to which the typists had now moved) ran with moisture and we spent most of our off-duty time huddled in bed drinking steaming cocoa. Sometimes it was so cold that we lay, facing upwards like Russian soldiers left to die in the Baltic wastes, Balaclava helmets over our foreheads and arms straight down by our sides.

5

Later on, with an increasing need for work and living space, especially with the additional US personnel, more accommodation huts were put up in Wittington Woods opposite the main gates. Diana Byron recalls:

Our hut accommodated nine WAAF officers, ablutions took place in a block outside in the woods and a stove kept us warm – we all took turns in collecting firewood to feed the stove.

6

Although the huts in the woods were reasonably comfortable, they were damp and the surrounding wildlife took up residence with the humans. Clothes and shoes went mouldy and there was a permanent musty smell. Mice, woodlice and spiders abounded and the hot weather brought out the mosquitoes.

Jeanne Adams:

I did my six months in the ranks at Medmenham living in a Nissen hut with 32 other girls. We all worked on different watches so sleep was a problem for us all. Our only heat was from a huge, black iron stove in the middle of the hut, which had to be stoked frequently, day and night, to keep us warm. The ablutions were primitive with no mains drains and a dreadful cart which came round each day to empty the loos. The baths and showers were shared by four huts full of girls and were pretty grim. I used my tin hat as a very effective shower cap and when inverted it carried my soap and toiletries. One night when the orderly officer came round at about 10pm to ask if we had any complaints, I foolishly told her that we had a blocked drain. I was told to come along with her and unblock it. I learnt not to complain!

7

Corporal Pat Peat was posted into RAF Medmenham in spring 1942 and shared a Quonset hut with fifteen other women:

There was a coal stove in the centre of the hut – some of the women stole coal from the store so we were always warm. Toilets and showers were down at one end of the hut. We had an inspection every morning. There was one bath tub and each week we were each allowed 2 inches of hot water for a bath. A group of five of us decided to pool our hot water ration to make one full tub every week and rotate who went in first. It was heavenly to have a full 10 inches to wallow in. I also went up and down the hut when I first got there to see who did the best cleaning of shoes, the best ironing and so on, then each did the task we were best at for the others. I did the buttons because I was the best at metalwork. We were always the best turned out WAAFs.

8