Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos (23 page)

Read Women of Intelligence: Winning the Second World War with Air Photos Online

Authors: Christine Halsall

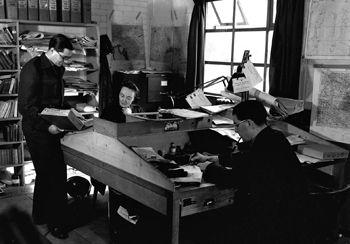

Charlotte Bonham Carter at work in the Ground Intelligence Section.

The search for information on a new project or query from any section at Medmenham usually began in the Ground Intelligence Section, responsible for keeping all reports from ground sources, including an extensive reference library of maps, charts, guidebooks, periodicals, trade and telephone directories. There were also illustrated brochures, plans and handbooks of industrial processes produced by companies in pre-war Germany, which were consulted by the Industry Section in the search for oil plants. Early on, the ACIU was refused access to information from the interrogation of prisoners of war and agent’s reports, as it was thought that interpreters would be biased and find on their photographs ‘what they had been told was there’. In no other form of scientific thought involving logical deduction had it ever been suggested that those carrying out the work would be biased by being provided with supplementary information, nor was there any evidence that such a tendency had ever been shown by photographic interpreters. The imaginative use of ground information in conjunction with photographic evidence actually served to enlarge the scope of photographic interpretation and helped develop new techniques.

Anne Jeffery had graduated in classics and archaeology from Newnham College, Cambridge, and spent some years in Athens before war intervened when she enrolled as a VAD nurse before volunteering for the WAAF in 1941. Her keen attention to detail, visual memory and archaeological knowledge soon brought her to Medmenham, but it was found that her stereoscopic vision was lacking, so her time was spent on intelligence rather than interpretation. Anne worked in Ground Intelligence with Charlotte Bonham Carter and Flight Lieutenant Villiers David. He lived with his sister at Friar Park, in Henley-on-Thames, the same house lived in years later by the Beatle, George Harrison. There are as many anecdotes concerning Villiers as there are about Charlotte, including one that Ann McKnight-Kauffer recounted:

When at last Villiers got rid of his Rolls Royce and chauffeur he got a motorbike. On the first morning he came to Medmenham on it, he found to his horror that he didn’t know how to stop it. He did the circuit from front gate to house past the much-amused guards until his petrol ran out.

13

There were many tennis and croquet parties held at Friar Park and sometimes Scottish dancing, when ‘Villiers leaping about in red braces was a sight to behold’.

14

Joan Bohey had good reason to be grateful to Villiers David for his hospitality, as it gave her an opportunity to meet her future husband, David Brachi, on social occasions. They had initially met through scouting, as Joan helped with the Cub pack in Marlow and David was associated with the Henley Scouts. Later on, when they started going out together, it had to be in secret, as Joan was an NCO and David an officer; such liaisons were not only frowned upon, but were against King’s Regulations. For that reason Joan never wore her uniform when they met on a date, instead wearing a variety of civilian clothes gleaned from other women in her hut. They had very little space for storing personal clothing and usually uniforms were worn for all on- and off-duty occasions. Joan and David could meet at Scout and Cub functions and at several houses whose owners, Villiers in particular, were sympathetic to their plight:

We used to go to Villiers David’s house – Friar Park – where all the light switches and door handles were shaped like monk’s heads, so you pressed down the monk’s nose to turn on the light! He and his sister had bought the farm next door so there was butter and cream at meals which was such a treat.

15

It has often been noted that RAF Medmenham resembled more of an academic institution than a military establishment, with men and women recruited from widely diverse civilian occupations. The early, informal recruitment for the RAF of suitable, academically qualified colleagues at Wembley was successful and was formalised under Wing Commander Hamshaw Thomas at Medmenham. The WAAF selection system was also successful in picking out potential women PIs, and not only the obvious choices with qualifications and experience in photography, archaeology, art and geography. Historians and English graduates were also among those recruited, as were the women who had shown at a selection board that they looked at and examined a subject in depth, seeing more than the superficial view.

Although the comprehensive collection of men and women working alongside each other at Medmenham were experts in the widest variety of specialist subjects, all had a common characteristic: none took things at their face value and all questioned whatever they saw on the photographs. Searching for clues under the stereoscope, examining something unusual and then following it up until the answer was found became second nature to them. From 1940, as soon as WAAF regulations allowed, women were employed on the same work as men and were recognised as being equally capable. They were given responsibility for decision making in all aspects of intelligence production at Medmenham.

Notes

1

. Churchill, Sarah,

Keep on Dancing

, pp.62–3.

2

. Scott (

née

Furney), Hazel, interviewed for BBC

Operation Crossbow

, 2011.

3

. Daniel, Glyn,

Some Small Harvest

(Thames and Hudson, 1986), p.98.

4

. Stone, Geoffrey, letter, 2011 (Medmenham Collection).

5

. Scott, Hazel (

née

Fu rney), conversation with the author, 2010.

6

. Babington Smith, Constance,

Evidence in Camera

(Chatto & Windus, 1958). Extracts from

Evidence in Camera

are reprinted by permission of Peters Fraser & Dunlop

(www.petersfraserdunlop.com)

on behalf of the estate of Constance Babington Smith.

7

. Morgan (

née

Morrison), Suzie, interviewed for BBC

Operation Crossbow

, 2011.

8

. Collyer (

née

Murden), Myra, interviewed for BBC

Operation Crossbow

, 2011.

9

. Carter, Joan, IWM papers.

10

. Duncan, Jane,

My Friend Monica

, pp.259–60, 262.

11

. Powys-Lybbe, Ursula,

Eye of Intelligence

, p.147.

12

. Brachi (

née

Bohey), Joan, in conversation with the author, 2011.

13

. Rendall (

née

McKnight-Kauffer), Ann, interview with Constance Babington Smith, 1956/7, (Medmenham Collection).

14

. Scott, Hazel,

Peace and War

, p.53.

15

. Brachi (

née

Bohey), Joan, conversation.

ILLIONS OF

P

HOTOGRAPHS

Squadron Leader John Saffery DSO DFC flew PR Spitfires from RAF Benson in 1943–44 and commanded 541 Squadron. He married Margaret Adams, a WAAF PI who worked in Second Phase at RAF Medmenham. He wrote graphically about flying at high altitudes while on solo photographic missions:

It is the climb through the tropopause into the stratosphere which is like crossing the bar from the shallows into deep water. The climb up has been a matter of constant change. The continually falling temperature, successive layers of cloud, varying winds, the appearance of trail, and the turbulence or vertical movements of the air are liable to be felt to a greater or lesser degree all the way up.

There was always the fear of passing out with very little warning if anything went wrong with the oxygen system, and to guard against this I used to keep a fairly elaborate log because I reckoned that if I could write legibly I must be alright. Nevertheless until the arrival of pressure cabins we were a bit slow witted from lack of oxygen I think.

The cold, the low pressure and the immobilising effect of the elaborate equipment and bulky clothing in the tiny cockpit had the effect of damping down and subduing all the senses except the sense of sight. One became just an eye, and what one saw was always wonderful.

On a clear day one could see immense distances, whole countries at a time. From over the middle of Holland I have seen the coast from Ostend round beyond Emden, and from the neighbourhood of Hanover seen the smoke pluming up from burning Leipzig. I’ve seen the Baltic coast from above Berlin and from over Wiesbaden seen the Alps sticking up like rocky islands through the clouds. On such days, which are rare in Europe, it was more like looking at a map than a view.

After 1942 the cabins were heated and a temperature of slightly above freezing was maintained so that we flew in battle dress with thick sweaters, long woollen stockings, double gloves and flying boots, but electrically heated clothing was not necessary. But the air temperature outside was 60 or 70 degrees below and if, as occasionally happened, the cabin heating failed, the cold was agonising. Everything in the cockpit became covered with frost and long icicles grew from the oxygen mask like Jack Frost’s beard. Most alarming of all, the entire windscreen and blister roof was liable to frost up so that one could not see out at all except where one rubbed the rime off with a finger to have a frenzied peep round through the clear patch before it froze over again. At such times one felt the air was full of Messerschmitts.

1

Only the PR pilots operated at such heights for long periods. In mid-June 1944, shortly after D-Day, John had to bale out of his Spitfire into the English Channel where he spent a day ‘bobbing about’ until he was picked up by a passing motor torpedo boat.

The photographs that the PR pilots took were mostly ‘verticals’, taken directly above the target from cameras fitted through portholes in the floor of the aircraft. These could also be used in sequence to provide a run of stereo pairs for intelligence gathering or as smaller-scale photographs for map making. Cloud was the greatest handicap to obtaining good photographs. The most successful pilots were those who appreciated the need for meticulous flight planning and good meteorological briefing. Photographs could also be ‘obliques’ taken sideways from the aircraft or, less commonly, to the front or rear, and these provided a wider view of an area. Low-level obliques were used to take pictures of targets which would otherwise have been obscured by cloud or for which information could not be obtained by any other means. This was known as ‘dicing’ and the elements of surprise and speed were essential. It was therefore very dangerous and carried out by only the most experienced pilots, producing some of the outstanding photographs of the war.

Great advances in camera and film technology took place during the Second World War, largely due to work at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough. Longer lenses, designed for high-flying aircraft, provided better spatial definition and showed more ground detail. Improvements in film emulsions increased sensitivity and resolution, while better camera mountings in aircraft eliminated the effects of vibration. The end result of all these advances was a reduction in the effect of film grain and a clearer picture when viewed by PIs through a stereoscope.

As soon as a PR aircraft returned to base, the photographic personnel took charge of the film for immediate processing, followed by First-Phase interpretation. Pamela Howie was a photographic processor at RAF Benson, dealing with the film from 1 PRU sorties.

Pamela, aged 19, had received her call-up papers in the summer of 1942, so left her job as librarian in Boots the Chemist’s library in Kendal, and enrolled in the WAAF at Carlisle where she was rated medically A1, despite having had asthma for several years. She reported to RAF Bridgnorth in Shropshire for kitting out and quickly learnt a thing or two about communal living:

At lunch on returning from the tea queue I found my knife and fork missing. Nobody had seen anything so armed with spoon and mug I went to the Corporal who said, ‘You only get one issue so you will have to steal them back again!’ At teatime I found a knife just lying on a table so snatched it!

2