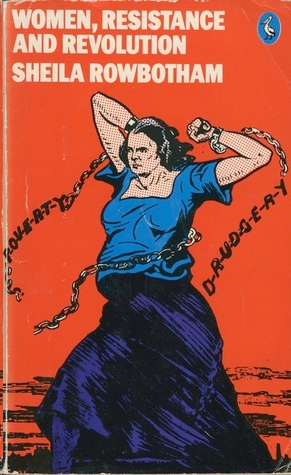

Women, Resistance and Revolution

Read Women, Resistance and Revolution Online

Authors: Sheila Rowbotham

This edition published by Verso 2014

First published by Vintage Books 1974

© Sheila Rowbotham 1974, 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-146-6

eISBN (UK): 978-1-78168-509-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78168-200-5

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

Chapter 3. Dialectical Disturbances

Chapter 4. Dreams and Dilemmas

Chapter 6. If You Like Tobogganing

Chapter 7. When the Sand-Grouse Flies to Heaven

Chapter 8. Colony Within the Colony

Acknowledgements

The idea of writing this book came partly out of discussions with Arielle Aberson who was killed very soon after in a car crash, and it is in her memory.

For help in finding some of the sources, thanks to Sue Finch, Christopher Hill, Thomas Hodgkin, Bessie Leigh, Betty Patterson, Penny Pollit, Alan Rooney, Marion Sedley, Wilhelmina Schroeder, Ken Weller, Barbara Winslow.

Also, for permission to consult their libraries: the Institute for Social History, Amsterdam, and the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding, and the T.U.C.

For laboriously reading the manuscript and telling me what they thought about it, love and gratitude to Arsenal Women’s Liberation Workshop Group, Stephen Bodington, Sharon Collins, Suzie Fleming, Roberta Hunter Henderson, Vivien Lewes, Laura Mulvi, Neil Middleton, Juliet Mitchell, Jean McCrindle, Teresa Moriarty, Bob Rowthorn, Anne Scott, Amanda Sebestyen, Dorothy and Edward Thompson, Micheline Victor, Lucy Waugh and David Widgery, who also lived with it. But I didn’t take notice of all their criticism and they are not responsible for the final version.

Thanks to Dr Michael Leibson, the cake stall on Ridley Road, Starcross Comprehensive, and the Workers’ Education Association who gave me the employment to survive while I was writing it, and to the people in women’s liberation and the socialist movement who gave me the confidence to do it.

I am grateful for permission to quote from Elizabeth Sutherland,

The Youngest Revolution

, Pitman & Sons Ltd; R. A. J. Schlesinger,

Changing Attitudes in Soviet Russia

, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd and Humanities Press; Chin P’ing Mei,

The Adventurous History of Hsi Men and his Six Wives

, translated by Arthur Waley, The Bodley Head; Edith Thomas,

The Women Incendiaries

, Editions Gallimard; M. Kent Geiger,

The Family in Soviet Russia

, Harvard University Press; Maxwell Bodenheim, ‘To a Revolutionary Girl’, in

New Masses

, an Anthology, International Publishers; Jessica Smith,

Women in Soviet Russia

, Vanguard Press Inc.; Felix Greene, description of a divorce trial in China,

The Wall has Two Sides

, Jonathan Cape; Helen Foster Snow,

Women in China

, Mouton; Keith Thomas,

Women and the Civil War Sects, Past and Present

; Francis Fytton, ‘Manifestation’,

Stand

magazine; Roxane Witke, ‘Mao Tse-tung, Women and Suicide’,

China Quarterly

; Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding publications; Shrew Collective; London Women’s Liberation Workshop; Comment; the International Institute for Social History for use of the minutes of the East London Federation of the Suffragettes; Sheffield Public Library for use of the Carpenter Collection. And to the workers of the British Museum who searched in the stacks of the B.M. to find them all for me.

Introduction

This is not a proper history of feminism and revolution. Such a story necessarily belongs to the future and will anyway be a collective creation. Instead I have tried to trace the fortunes of an idea. It is a very simple idea, but one with which we have lost touch, that the liberation of women necessitates the liberation of all human beings. I have tried to describe the circumstances in which such a notion could come about, and indicate something of how it has manifested itself. I have tried to pursue it as a living reality as it came into and out of the lives of particular men and women, and as a political reality as they organized to act upon it. I wanted to communicate the manner in which it has changed and appeared in a different guise, assuming new shapes when it became practical. Even so there is much which I have not mentioned and much that I do not know and more that I couldn’t fit in. It will be a useful book only if it is repeatedly dismantled and reconstructed as part of a continuing effort to connect feminism to socialist revolution. It contains no blueprint for what we should do in the future; it simply puts together some of the things we have already done, so that we can understand a little more clearly where we are starting from. It is a tentative first step towards correcting the masculine bias in the story we have inherited of our revolutionary past.

Women have come to revolutionary consciousness by means of ideas, actions and organizations which have been made predominantly by men. We only know ourselves in societies in which masculine power and masculine culture dominate, and can only aspire to an alternative in a revolutionary movement which is male defined. We are obscured in ‘brotherhood’ and the liberation of ‘mankind’. The language which makes us invisible to ‘history’ is not coincidence, but part of our real situation in a society and in a movement which we do not control. Our subordination is so deeply internalized that

it has taken women’s liberation to reveal it. The pain, emotional violence, and intense rejection of the male-defined revolutionary movement, which some women have expressed as part of a specifically feminist consciousness, are inseparable from that invisibility.

There are two immediate responses to this pain. One is subservient acquiescence to the male revolutionary’s definition of our role. Out of ‘loyalty’ or the need to preserve ‘unity’ we allow our daring and imagination, so briefly and recently released, to be once again restricted and held down, contenting ourselves with token acknowledgement. The other response is an angry denial that ‘their’ movement is anything to do with us. We decide to seek our new selves alone. While the first lets go of the explicitly female consciousness and pretends that the specific oppression of women does not exist, the second isolates female consciousness from any other movement for liberation and pretends that men are not oppressed in the world outside.

The paralysis of a male-defined revolutionary movement is as evident as the paralysis of a consciousness which can comprehend only the liberation of women. Both are caught in their own particularity. The attempt to touch, recognize and communicate the effort to go beyond this paralysis in the past is part of the task of working it through in theory and practice in the future.

Without a movement as a reference point, without the ideas expressed in that movement, and without the constant support and help of the women I know in women’s liberation, I would never have written more than a fragment of this. Women’s liberation brings to all of us a strength and audacity we have never before known.

I am not however speaking

for

anyone. What I write is simply a contribution to a permanent communication, which comes from me personally but only exists because of other women. An individual woman who appears as the spokeswoman for the freedom of all women is a pathetic and isolated creature. She is inevitably either crushed or contained as a sexual performer. No woman can stand alone and demand liberation

for

others because by doing so she takes away from other women the capacity to organize and speak for themselves. Also she presents no threat. An individual ‘emancipated’ woman is an amusing incongruity, a titillating commodity, easily consumed. It is only when women start to organize in large numbers that we become a political force, and begin to move towards the

possibility of a truly democratic society in which every human being can be brave, responsible, thinking and diligent in the struggle to live at once freely and unselfishly. Such a democracy would be communism, and is beyond our present imagining.

CHAPTER 1

Impudent Lasses

By God, if wommen hadde written stories,

As clerkes han with-inne hir oratories,

They wolde han written of men more wickednesse

Than all the mark of Adam may redresse.

Chaucer, The Wife of Bath’s Prologue,

The Canterbury Tales

It may be thought strange and unbecoming in our sex to show ourselves by way of petitions.… [But] … Christ has purchased us at as deare a rate as he hath done Men, and therefore requireth the like obedience for the same mercy as of men.

… In the free enjoying of Christ in His own laws and flourishing estate of Church and Commonwealth consisteth one happinesse of women as of men.

… Women are sharers in the common calamities that accompany both Church and Commonwealth, when oppression is exercised over the Church or Kingdome, wherein they live; and an unlimited power has been given to prelates to exercise over the consciences of women as well as men, witnesse Newgate, Smithfield, and other places of persecution wherein women as well as men have felt … their fury.

Women’s petition to Parliament, 1642

– against Popery

Our desire is to shut up our kitchen doores from eight in the morning till eight at night every second Tuesday in the month unless some extraordinary business happen to keep them open; if so to enjoy an equivalent and conscientious liberty another day, but our City Dames are so nice that they will put in anything for an exception, and in case of rainy weather they may detaine us … therefore let it raine, haile,

snow or blow never so fast; we would have leave, at our discretion, to take up our coats and steere our course as we please.

Maid’s Petition, 1647 – against the ‘uncontrollable impositions of our surly Madams’

[Women] appeare so despicable in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances.… Can you imagine us to be so sottish or stupid, as not to perceive, or not to be sensible when daily those strong defences of our Peace and Welfare are broken down and trod underfoot by force or arbitrary power? Would you have us keep at home in our houses while men … are fetched out of their beds and forced from their houses by souldiers, to the affrighting and undoing of themselves, and their wives, children and families.… Shall we sit still and keep at home.

Petition in favour of Lilburne’s release, 1647

We have for many years chattered like Cranes and mourned like Doves.

Petition against the law on debt, 1651

When Men unto their Wives make long beseeches

The Women domineer who wear the Breeches

Their tongues, their hands, their wits to work they set,

And never leave till they the conquest get.

… Nothing will serve them when their finger itches

Until such time they have attained the Breeches.

‘The Women’s Fegaries shewing the great endeavour they have used for obtaining of the Breeches’, c. 1675

If you love yourselves you must love your Wives and Children which are part of yourselves, and this suggests to you the demand they have upon your Labour and Industry in order to make a decent and comfortable Provision for them.

Rev. Edward Whitehead,

‘The Use and Importance of Early Industry’, 1753