Women Sailors & Sailors' Women (40 page)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This has been a surprisingly difficult book to write. My first forays in libraries revealed masses of material about mermaids but very little about real women who went to sea. There were plenty of journals and memoirs written by seamen, but there seemed to be remarkably few written by seafaring women. The biographies of the few well-known women sailors were all written by men and contain a great deal of undocumented and dubious material. And then I came across Suzanne Stark's book,

Female Tars,

which uncovered and analyzed the facts about women in the Royal Navy. This confirmed my suspicions about some of the stories of female sailors but also preempted much of what I had intended to write about.

I therefore decided to change tack and to look beyond the stories of women sailors to the relationships between seafarers and their women, afloat and ashore. It soon became apparent that several volumes would be required to do justice to such a fascinating subject, so I limited myself to the Anglo-American maritime world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and selected a number of representative characters and areas within that period. I am acutely aware that I have only scraped the surface and that there is much more material waiting to be unearthed.

In some chapters, I have made several references to popular prints and paintings of the period because these not only provide useful information on the appearance of seafaring men and women, their clothes, their houses, the streets they lived on, and their harbors and ships, they also reflect contemporary attitudes to sailors and their women. Because of production costs and high reproduction fees, only a selection of these pictures appear in this book, but many of these images will be shown in exhibitions that are being planned, notably the exhibit at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, Virginia, which is entitled

Women at Sea

and opens in March 2001.

The staff at the Mariners' Museum have been endlessly helpful during the preparation of this book, and I would like to acknowledge the financial assistance they have given me as guest curator. In particular, I would like to thank the following: John Hightower, the president of the museum; Claudia Pennington, the former director (now executive director of the Key West Museum of Art and History); Bill Cogar, chief curator and vice president; Karen Shackelford, who has been largely responsible for the preparation of the exhibition; Benjamin H. Trask, who supplied me with a constant stream of information; and the staffs of the library and the education department.

I would also like to thank Suzanne Gluck, my agent in New York, and Gillian Coleridge, my English agent, for their constant support, and to thank the editorial staff of my publishers at Random House, New York, and at Macmillan in London for their good advice and sympathetic editing. Tanya Stobbs, Becky Lindsay, and Nicholas Blake were particularly helpful. I would also like to record my thanks to David Moore, Stephen Jaffe, Pieter van der Merwe, Peter and Mary Neill, Elisabeth Shure, Jo Stanley, and Pamela Tudor-Craig, as well as to the staff at the Library of Congress, the British Library, the London Library, and the Public Record Office, and my former colleagues at the National Maritime Museum, London.

The Notes and Bibliography indicate the sources that I have used in writing this book, but I would like to record my debt to four writers in particular. The first is Antonia Fraser, whose biographies are legendary and who encouragingly wrote in her preface to

The Weaker Vessel,

“After all, to write about women it is not necessary to be a woman, merely to have a sense of justice and sympathy.” The second is Linda Grant de Pauw, whose pioneering work,

Seafaring Women,

I vividly recall reading and enjoying during one of my visits to the Library of Congress. The third is Suzanne Stark, whose

Female Tars

I have already mentioned. And the fourth is Joan Druett, another pioneer in the study of seafaring women, who has published a succession of fine books on the subject. Her most recent book,

She Captains,

fortunately appeared after I had completed work on this book. Otherwise, I might have been tempted to abandon it and go back to the drawing board.

Finally, I would like to thank my daughter, Rebecca, who kept me on track when sometimes I could not see the forest for the trees; and my wife, Shirley, who helped me the most and to whom this book is affectionately dedicated.

D.C.

Brighton, Sussex

September 2000

About the Author

D

AVID

C

ORDINGLY

was for twelve years on the staff of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, where he was curator of paintings and then head of exhibitions. His book

Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates

is considered the definitive account of the great age of piracy. He is a graduate of Oxford and received his doctorate from the University of Sussex. Cordingly now works as a writer, and lives with his wife and family by the sea in Sussex.

Also by David Cordingly

Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates

PHOTO INSERT

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

One of the many popular prints devoted to the theme “the sailor's farewell” made in the late eighteenth century. The young sailor's gesture toward the gun and the flag suggests that he is torn between his love for his sweetheart and his patriotic duty to fight for his country.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

An engraving by Thomas Rowlandson, entitled

Sea Stores,

shows a naval officer negotiating with prostitutes on the waterfront at Plymouth. The officer has just come ashore from a ship in the harbor and is eager to get down to business.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

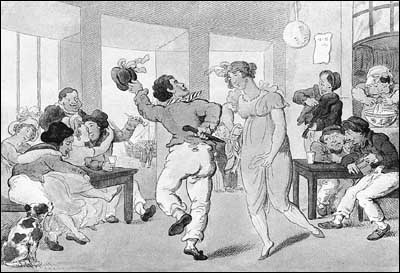

A sailor enjoys his last moments ashore in this engraving by Thomas Rowlandson,

Dispatch, or Jack preparing for sea.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

Thomas Rowlandson depicts a typical scene in a seaman's tavern in the 1790s. The location is Wapping, the sailors' district on the north bank of the Thames near London Bridge and the Port of London.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

This is a detail from a well-known engraving by Thomas Rowlandson,

Portsmouth Point.

The fleet is about to sail, and sailors of all ranks are saying fond farewells to their loved ones before being rowed out to the anchored warships.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

An engraving of a cabin boy by Thomas Rowlandson. There were many boys aged from nine or ten and up on warships. They wore loose, baggy clothes and often wore their hair long, which helps explain why young women were sometimes able to pass themselves off as adolescent boys without being discovered.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

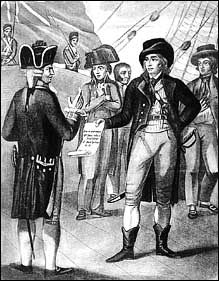

Richard Parker, the leader of the Mutiny at the Nore, hands a list of the sailors' grievances to Vice-Admiral Buckner on board HMS

Sandwich.

The mutiny began on May 12, 1797, and spread to most of the warships anchored off Sheerness at the mouth of the Thames.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

A portrait of Richard Parker, who was condemned to death for his part in the Mutiny at the Nore. Parker's wife, Ann, failed to get a reprieve for him and arrived at the fleet anchorage at the Nore too late to speak to him but not too late to see him hanged.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

Mary Anne Talbot, who, according to her biographer, served in the British army and the Royal Navy under the name John Taylor in the 1790s. Engraving by G. Scott, after the portrait by James Green.

©N

ATIONAL

M

ARITIME

M

USEUM,

L

ONDON

Mrs. Hannah Snell, who joined the British army in the 1740s, served as a marine at the siege of Pondicherry in India and then joined the navy as a seaman. Her shipmates were astonished when she eventually revealed that she was a woman.