Wonder Woman Unbound (7 page)

Read Wonder Woman Unbound Online

Authors: Tim Hanley

In the end it was Catwoman who most resembled the Golden Age Wonder Woman. They both used men and eschewed romantic entanglement, working to accomplish their own goals regardless of societal expectations. But while they shared similar traits, they had completely different roles. Catwoman embodied these traits in a framework meant to reinforce typical gender roles, and so she had to be shown in a bad light. Wonder Woman was focused on inverting typical gender roles, and so she took those traits that were so often negatively portrayed and embodied them in a positive and heroic light. Catwoman had transgressed the patriarchal social order, and because of it had to be a crook, but Wonder Woman was establishing a new matriarchal social order and she was its heroic model.

The Inverted World of Wonder Woman

Discussing the creation of Wonder Woman in a 1943 article in the

American Scholar,

William Moulton Marston wrote that “not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, power.” Marston suggested that most comic book readers had disdain for female characters because they showed only the “weak” qualities of women, and he argued that “the obvious remedy [was] to create a feminine character with all the strength of a Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.”

In Wonder Woman, Marston presented a brand-new kind of character. While his ideas about female superiority never really caught on, the long-term impact of the first powerful, independent female superhero cannot be understated. In a genre that so rigidly enforced typical gender roles and relied on a very narrow view of femininity, Wonder Woman shattered these expectations for millions of young readers each month. It’s sometimes hard to see the ingrained societal structures that dictate daily life, but by inverting these structures Wonder Woman comics shed a light on the tenets of these systems, along with a sharp critique.

Marston intended to prepare boys for matriarchy, but it seems that girls got the most out of the comics. It can’t just be a coincidence that the first generation of girls raised on empowering female characters like Wonder Woman and Rosie the Riveter became the generation of the women’s liberation movement. Marston’s Wonder Woman was a wholly unique character in the Golden Age of comics, and while his theories may have been problematic, the legacy of his creation lives on still.

*

Robbins is the foremost expert on women in comics; her book

The Great Women Superheroes

recounts the stories of Golden Age heroines who have been long forgotten.

†

Miss Fury is particularly noteworthy because she was written and illustrated by June Tarpé Mills, one of the few women making comics in the Golden Age. She created the strip under the pseudonym Tarpé Mills, dropping her first name to hide her gender. Miss Fury strips were collected in comic book form in several issues from 1942 to 1946.

*

In fact, “Diana Prince” was literally someone else entirely. In

Sensation Comics

#1, soon after Wonder Woman arrived in America she met a nurse who was crying because her husband had found a job in South America and she couldn’t afford to go be with him. The two women looked exactly alike, so Wonder Woman gave her money to go join her husband in exchange for taking over her identity.

*

Lois ignored this demand and was at her editor’s desk the next morning trying to get the story published, but her editor didn’t believe her. Every man in Lois’s life actively kept her down.

*

This slowly changed over time, and Lois got a cover story here and there, though it was often only because Superman felt bad and let her have one. Years into the series, Clark was still out-scooping Lois at almost every turn. Lois is fascinating in that she so well embodies the progress and limitations of working American women in the late 1930s. That Lois even had a job was impressive considering that only a quarter of American women worked outside the home at the time, but being relegated to a position with very little room for advancement in a hostile work environment was the unfortunate plight of many working women.

3

Amazon Princess, Bondage Queen

W

hile the Golden Age Wonder Woman was impressive, there was more to her than just fighting crime. Her adventures, from helping a bullied child to saving the world from alien invaders, gave her a range Superman and Batman didn’t have. Wonder Woman was a superior superhero, and intentionally so. William Moulton Marston believed that every woman could be a metaphorical Wonder Woman and that women would soon take over the world. His worldview was unique, remarkably progressive, and all of his theories were channeled into his creation. Many of Wonder Woman’s early stories still stand up as strikingly feminist seventy years later, even compared to modern comic books and female characters in today’s books, TV shows, and movies.

*

All of Marston’s work preached a strong message about female power, and while his vision of a female-ruled society hasn’t panned out yet, it was nonetheless a rather forward-thinking idea. However, the more we dig into the subtext and metaphors of his work, the more another side of Marston emerges. His comics were rife with bondage imagery, adding a sexual component to the books that reflected his own fetishism and the troubling places it could lead.

The rampant fetishism in Wonder Woman comics complicates their feminist message, but it doesn’t undermine it. In fact, the feminism and fetishism were inextricably linked, both of them deriving from Marston’s psychological work. You can’t have one without the other.

A Staggering Amount of Bondage

The idea of Wonder Woman as a bondage queen may seem farfetched. Getting captured and tied up by bad guys is an occupational hazard when you’re a superhero, so some argue that while Wonder Woman got tied up sometimes, so too did everyone else. In

The Great Women Superheroes,

Trina Robbins makes an interesting Golden Age-specific argument about Captain Marvel. Robbins points out that because Billy Batson had to say “Shazam!” to turn into Captain Marvel, he often ended up bound and gagged by fiendish villains so he couldn’t transform into a superhero and thwart their plans. Similarly, Wonder Woman’s main weapon was a lasso, which she used to tie up a lot of people in her comics. Both characters had reasons to have an abnormal amount of bondage in their stories.

A comparative analysis of the first ten issues of

Captain Marvel Adventures

with the first ten issues of

Batman

confirms Robbins’s initial point. Be it ropes or chains or gags, anytime someone was bound and restrained in a way that encumbered or incapacitated him or her, that panel was noted.

Batman

was chosen for two reasons: the book was never really associated with bondage, and Robin was always tagging along so there were two heroes to be captured and tied up.

The overall percentage of bondage in both series was the same with each coming in at about 3 percent, but in terms of personal bondage there was a clear winner. On average, Batman and Robin combined were tied up in only 1 percent of the panels in

Batman,

while Captain Marvel was bound in

Captain Marvel Adventures’

panels twice as often. This is a sizeable difference, particularly since it was one hero’s total against two.

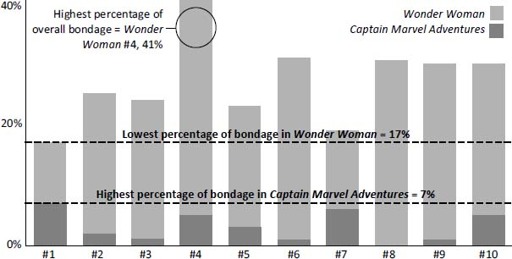

Captain Marvel was definitely tied up more than the average superhero, but his numbers get dwarfed by Wonder Woman.

The chart below shows how often Captain Marvel and Wonder Woman were bound in the first ten issues of their own series, debunking the “all superheroes get tied up” argument. Wonder Woman’s lowest percentage of personal bondage in

Wonder Woman

was the same as Captain Marvel’s highest percentage of personal bondage in

Captain Marvel Adventures.

When your worst is the same as the other guy’s best, that’s a substantial amount. The averages show the same divide: Captain Marvel was tied up about 2 percent of the time in his books, and Wonder Woman was tied up 11 percent of the time in hers. Captain Marvel doubling Batman and Robin’s personal total was fairly impressive, but Wonder Woman trumps Captain Marvel more than five times over.

In

Wonder Woman

#10, one out of every five panels in the issue showed Wonder Woman tied up in some fashion. The series was drawn on a six-panel-per-page grid, so on average Wonder Woman was tied up at least once a page in that issue. That’s excessive on its own, but other people were tied up in

Wonder Woman

as well.

The following chart shows the total amount of bondage in

Wonder Woman

and

Captain Marvel Adventures,

including the heroes plus everybody else who happened to be tied up. If

Captain Marvel Adventures

#1, the issue with the highest amount of bondage, doubled its total, it still wouldn’t reach

Wonder Woman

’s lowest total. On average,

Captain Marvel Adventures

contained 3 percent total bondage, while

Wonder Woman

had 27 percent. That’s more than a quarter of the book and amounts to nine times as much bondage as

Captain Marvel Adventures,

our paradigm of an above-average bondage comic book.

These numbers are colossal, and they get even more curious when comparing personal and overall bondage. Captain Marvel accounted for most of his book’s bondage. His personal total was 2 percent and the overall total was 3 percent, so Captain Marvel comprised two-thirds of the book’s bondage, a clear majority at nearly 70 percent. Wonder Woman was tied up 11 percent of the time, while her book’s overall total was a massive 27 percent; at 40 percent of the total bondage, this is a minority. Sixty percent of the bondage imagery in

Wonder Woman

didn’t actually feature Wonder Woman at all. Marston spread the bondage around to other characters.

The bondage panels in

Wonder Woman

were both numerous and widespread. Going far beyond the occupational hazards of being a superhero, bondage in Wonder Woman comic books was a vast and all-encompassing phenomenon, and it was there for a reason.

Bondage and the Coming Matriarchy

Contemporary thought on bondage is much different than Marston’s approach. When we think of bondage these days, it’s usually in terms of the bondage/discipline, dominance/submission, and sadism/masochism subculture, conveniently amalgamated into the far easier to remember acronym of BDSM. This type of bondage has very specific associations with things like leather and whips and is usually tied to role-playing and escapism. For example, the businessman who runs a company all day and gets to boss people around goes home, puts on a leather unitard, gets chained to the wall, and lets someone with a riding crop be in charge for a while. It’s escapist and focuses on one party dominating the other.

For Marston, bondage was about submission, not just sexually but in every aspect of life. It was a lifestyle, not an activity, and he used bondage imagery as a metaphor for this style of submission. In 1942, Marston conducted a fake interview with his domestic partner, Olive Byrne, for

Family Circle

magazine. Byrne used the pseudonym “Olive Richard” and pretended to be a casual friend of Marston interested in Wonder Woman and his ideas behind her.

*

The article was called “Our Women Are Our Future” and it allowed Marston to spell out his theories on the coming matriarchy. Byrne, still upset over Pearl Harbor, asked Marston, “Will war ever end in this world; will men ever stop fighting?” He replied, “Oh, yes. But not until women control men.”

Patriarchy amounted to a lot of war, greed, and general strife and was motivated by aggression. It was a forced system where those in power weren’t looking out for everyone’s best interests. Marston told Byrne that he saw women taking over society “as the greatest—no, even more—as the only hope for permanent peace.” Men had to choose to surrender to the “loving authority” of women if things were going to get better.