Work Clean (14 page)

Authors: Dan Charnas

stage

Chef Wylie Dufresne transformed a Lower East Side bodega into a Zen monastery of molecular gastronomy. But by 2014, the Manhattan neighborhood that Dufresne helped revitalize with wd-50 was rapidly gentrifying. Developers snapped up empty parcels and old buildings around him to erect a condominium. Dufresne wanted to stay. The developers wanted him out.

While Dufresne fought, Sam Henderson and the staff at wd-50 tried to ignore the rumors, both in the restaurant and online, and keep working. Henderson had another job on her mind, one she had to keep secret from Wylie: coordinating a surprise dinner party for him in April, celebrating the restaurant's 11th anniversary. This epic modernist feast would be cooked by nearly two dozen of the world's finest chefs, including Iñaki Aizpitarte, René Redzepi, Gabrielle Hamilton, Daniel Boulud, and David Chang, each creating his or her own version of a Dufresne dish. Henderson felt like a

stage

again, surrounded by icons she had dreamed of meeting, and yet she had to tell these men and women where to stand and when to cook, and to make sure that they didn't make a mess of her kitchen.

The surprise party was a smash, with Wylie's mentor, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, in attendance; but it also turned out to be the prelude to a long goodbye. In June, Dufresne announced that he would fight no more: wd-50 would close in November. What happened in those intervening 5 months astonished Sam Henderson.

“Instead of the crew donning their life vests and jumping ship,” Henderson recalled, “everybody stayed put and did their job better than ever.” Alumni like Mike Sheerin, Simone Tong, and J.J. Basil returned to cook, and Dufresne's chef friends came to dine. “The last two nights were some of the best services we've ever had.”

On the last night, the cooks hugged, cried, cleaned, and drank. Many of them returned in the days that followed to help Dufresne tear the kitchen apart, and attended the auction where the plates

they wiped with care were sold for 50 cents apiece and the appliances they scrubbed until gleaming were dragged out by gloved laborers. It broke Henderson's heart to watch.

But being a former writer, she knew that an ending gives a story its meaning. The way wd-50 endedâin its prime, surrounded by familyâearned it an indelible spot in the history of global cuisine. Sad but not defeated, Henderson saw the ending was a new beginning. The restaurant would remain with her in more ways than one. Former sous-chef J.J. Basil was now her fiancé, and they planned to open up a place of their own.

She cleaned up, moved on, left nothing behind.

Recipe for Success

Commit to maintaining your system. Always be cleaning.

MAKING FIRST MOVES

A chef's story: The pan handler

Driving back to New York City after a Thanksgiving dinner upstate, Chef Josh “Shorty” Eden took a detour. He pulled off the Palisades Parkway in New Jersey and headed toward the home of his buddy Kamaalâthe name that the rapper Q-Tip's closest friends now called him. Eden dropped off a tray of leftovers, some roasted root vegetables. He left with a new employee.

Eden didn't think twice about offering Jarobi White a job. The chef needed bodies for his kitchen at August, the restaurant in Manhattan's West Village where he himself had just been hired. Eden liked helping friends. He met Q-Tip at his previous restaurant, Shorty's 32, and he had gotten to know Tip's erstwhile bandmate soon thereafter. They had all haunted the same downtown clubs in the 1980s and '90s, and they shared mutual friends, including Michael Rapaport, the actor who would soon direct the documentary on Q-Tip and Jarobi's group, A Tribe Called Quest. Eden wanted to help Jarobi go legit.

“If you're going around New York telling people you're a chef, don't just

say

you are. Do it,” Eden told him.

Hiring Jarobi meant breaking him down, forcing him to unlearn all the bad habits he had accumulated in the course of his career.

Wear an apron, Jarobi. Make sure your braids are up, Jarobi. Don't eat breakfast at your station, Jarobi.

In the heat of service, cooks pursue the quickest route between

taking an order and putting a plate in the window. Like all cooks, Jarobi took shortcuts. Eden tried to show him what shortcuts he could and couldn't take. Eden went for as many corny analogies to the music world as possible:

How many times did you cut that song before you put that record out? Slow down.

Or:

Learn how to fix things. When the show starts and you forget a line, do you stop and start over? No, you find your way through it.

Eden didn't care about Jarobi's semi-celebrity. When Jarobi messed up, Eden yelled at him just like he would anyone else.

You're supposed to be making my job easier, not harder.

Then he taught Jarobi the right way to do it.

Eden invested months training Jarobi, but the hours expended early on started to pay off. Eden put him on lunch service. The apprentice improved. Jarobi climbed through the stations. Then came the morning that Eden decided he could sleep late. Why? Because

Jarobi was in the kitchen, handling things

.

Jarobi worked for Eden for 3 years, until August closed. He left a bona fide New York cook. More than that, Jarobi had joined a noble family of chefs, a direct lineage that Eden could trace for him all the way back to France, beginning with Fernand Point, viewed by many as the successor to Escoffier in the evolution of French cuisine. Point trained Louis Outhier and Paul Bocuse. And a student of Outhier and Bocuseâa young Alsatian chef named Jean-Georges Vongerichtenâbrought that training with him to America, where in 1993 he met a hustling 23-year-old cook just out of the French Culinary Institute named Josh Eden. Now Eden had passed that training on to Jarobi White.

Eden mentored White in the same way that Vongerichten had mentored him. Jarobi called Eden his “Yoda”; Eden worshipped Jean-Georges: At the age of 29, Vongerichten earned four stars from the

New York Times

for his cooking at the Drake Hotel's restaurant, Lafayette. Then he took that food out of the hotel and into his first restaurant, JoJo, leaving the stuffiness and the high price behind. After Eden secured a spot low on the totem pole in JoJo's kitchen, he convinced Vongerichten that he could be useful by scouring the farmers' markets of New York every day for the

freshest produce. Vongerichten bought a van for Eden's errands. Eden drove that van until he totaled it.

Eden hadn't ripened yet and still required more energy than he generated. In Vongerichten's kitchen,

chef de cuisine

Didier Virot dubbed the stocky, compact cook “Shorty.” The nickname stuck. Vongerichten relentlessly criticized Eden's skills and moves. On fish station, Eden overcooked a piece of salmon, and the chef was all over him for the rest of the week. But Vongerichten always followed a slap with a caress. On Friday night, Eden cooked an end-of-service meal for Vongerichten, Virot, and the sous-chefs. The chef came down the line and threw his arm around Eden.

“I've been screaming at you every day. You're doing a good job. I just want you to learn.”

“Chef, you never need to apologize to me,” Eden replied. “I'm here to learn.”

Vongerichten produced a bowl of mousseron mushrooms. “Let me show you how to cook these like my chef taught me,” he said. Thus Josh Eden inherited the knowledge of another culinary legend and Bocuse contemporary, Chef Paul Haeberlin.

Above all his lessons, Vongerichten taught Eden the value of time. Rather than the simplistic notion that “every moment counts,” Vongerichten implied a more esoteric concept: The first moments count more than later ones.

On a busy night when the kitchen got pounded and the orders flew in, Vongerichten repeated a mantra: “Guys, pans on!”

Before you do anything else, make the first move: Get some damn pans on the stove, turn on the heat, and get them hot.

The first reason for Vongerichten's admonition was mental: Working at such a fast pace, cooks need reminders. Each pan, in effect, becomes a placeholder for an order. A cook can look at the stove and see, at a glance, a proxy for the work that needs to be accomplished. The second reason was physical: To properly brown vegetables and proteinsâto get that wonderful, crisp, and delicious external textureâthe pan and the oil in it need to be hot

before

the food goes in. It takes a certain amount of time to heat a pan, a minute or two. There are no shortcuts when it comes to that process. So

if a cook puts a pan down the moment an order comes in, he can get it hot while preparing or seasoning the ingredients that will go inside of it. But if he doesn't get that pan on, and preps the ingredients first, he'll still have to wait around for a minute after seasoning, like a jerk, for the pan to get hot. Those 2 seconds just cost him a minute later on.

The first moments count more than later ones.

It took a while for Eden to catch on, even after he had graduated from JoJo to become saucier at Jean-Georges. One evening Eden was getting crushed on his station. Working his way through a backlog of orders, he wasn't getting the food out fast enough, and tables were waiting for their meals. Upstairs came Jean-Georges's recently promoted sous-chef, Wylie Dufresne.

“Shorty,” Dufresne said, “when you're getting beat like that, you've got to throw a couple of extras in the pan. If you lose one at the end of the night, you lose one. Would you rather get screamed at or would you rather have the food ready to go?”

Dufresne was telling Eden that if the orders were coming in faster than he could manage, and he couldn't even manage to get new pans on the range, then at the very least throw some extra portions in the pans he did have cooking. It was a shortcut, yes. “Sandbagging,” crowding the pan and thereby reducing the heat, might change the texture and flavor of the dish. Cooking off too much protein in advance might waste food and money. Dufresne was counseling Eden that it was better to get screamed at by Vongerichten at the end of the night for raising his food cost than to enrage the staff and the customers by not having the food ready when it needed to be.

To be ready, you have to make first moves.

Chefs move now

How do we start?

The principle of making first moves is the chef's answer to that question

,

but it's universal wisdom about how to begin any project that involves a series of tasks.

My own chefâthe master from whom I learned to practice and teach yoga 20 years agoâhad a saying:

When the time is on you, start, and the pressure will be off.

I thought he was talking about momentumâlike writing the first sentence, making the first phone call, or rising up out of my chair to have a difficult conversation. I didn't grasp what my teacher was truly saying until years later when I started spending hours in professional kitchens. He was trying to teach me a more subtle and profound notion about the nature of time:

The present has incalculably more value than the future.

An action taken

now

has immeasurably more impact than a step taken later because the reactions to that action have more time to perpetuate. Furthermore, because our mind state has a huge effect on how we perceive time, acting in the present releases psychological pressure and opens up more time.

Starting is, in effect, a shortcut.

To mash metaphors: A stitch in time causes a wrinkle in time.

“We're in the weeds all day long,” Eden says. “But when service begins, service is easier, because we've done all our hard work already.”

The first few moments of your day or minutes of your project are crucial. They matter more than any others. A minute spent now may save 10 minutes, 20 minutes later on. The seasoned chef or cookâwith an unquenchable thirst to shorten the distance between “here” and “beer”âseizes those first moments for everything they're worth.

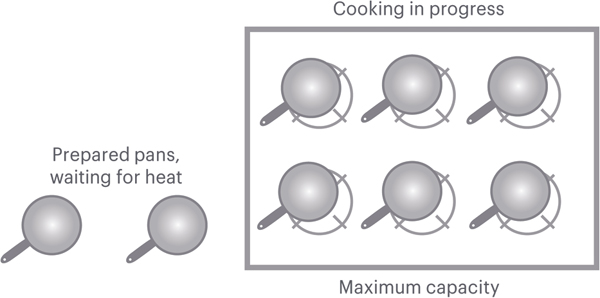

In the kitchen, orders don't arrive in a nice, steady stream. The work comes in waves, often at a pace that is too much for the mind to handle. At some point during a busy service, orders will flood in faster than a cook's ability to process them. Cooks in the weeds barely have time to reference the printed orders, on little curls of paper called dupes. Nor can they remember all the chef's or expediter's verbal commands. So cooks make first moves by setting reminders of the things that need to be done, especially when the things that need to be done arrive all at the same time.

To do this, cooks place a marker object in their visual field for each item to be accomplished. Getting a pan onto the stove is one way to make that first move. Placing raw ingredients on a platter or plate or cutting board is another.

Many of us live by the anti-procrastination aphorism, “Do the worst first.” Organization guru Stephen Covey gave us a related mantra, “First things first.” The thought behind both of these phrases is

do the thing that's the hardest or most important early, while you have the time and energy.

It's in this spirit that new culinary students rush into the kitchen thinking about executing the most difficult tasksâintricate knife cuts and complex preparations that need extra time and attention. Then, having done the “worst” first, their stomachs drop when they realize they should have done something

else

first, something rather quick and easy:

Turn the oven on

.