Works of Alexander Pushkin (69 page)

Read Works of Alexander Pushkin Online

Authors: Alexander Pushkin

All was over. The Turks remained victorious. Moldavia was swept clear of insurrectionary bands. About six hundred Arnauts were scattered over Bessarabia; if they did not know how to support themselves, they were yet grateful to Russia for her protection. They led an idle life, but not a dissipated one. They could always be seen in the coffee-houses of half-Turkish Bessarabia, with long pipes in their mouths, sipping coffee grounds out of small cups. Their figured jackets and red pointed slippers were already beginning to wear out, but their tufted skull-caps were still worn on the side of the head, and yataghans and pistols still protruded from their broad sashes. Nobody complained of them. It was impossible to imagine that these poor, peaceably disposed men were the notorious klephts of Moldavia, the companions of the ferocious Kirdjali, and that he himself was among them.

The pasha in command at Jassy became informed of this, and, in virtue of treaty stipulations, requested the Russian authorities to extradite the brigand.

The police instituted a search. They discovered that Kirdjali was really in Kishinev. They captured him in the house of a fugitive monk in the evening, when he was having supper, sitting in the dark with seven companions.

Kirdjali was placed under arrest. He did not try to conceal the truth; he acknowledged that he was Kirdjali.

“But,” he added, “since I crossed the Pruth, I have not taken so much as a pin, or imposed upon even the lowest gypsy. To the Turks, to the Moldavians and to the Wallachians I am undoubtedly a brigand, but to the Russians I am a guest. When Saphianos, having fired off all his grape-shot, came here, collecting from the wounded, for the last shots, buttons, nails, watch- chains and the knobs of yataghans, I gave him twenty

besh

liks, and was left without money. God knows that I, Kirdjali, have been living on charity. Why then do the Russians now deliver me into the hands of my enemies?”

After that, Kirdjali was silent, and tranquilly awaited the decision that was to determine his fate. He did not wait long. The authorities, not being bound to look upon brigands from their romantic side, and being convinced of the justice of the demand, ordered Kirdjali to be sent to Jassy.

A man of heart and intellect, at that time a young and unknown official, who is now occupying an important post, vividly described to me his departure.

At the gate of the prison stood a

caruta.

... Perhaps you do not know what a

caruta

is. It is a low, wicker vehicle, to which, not very long since, there were generally harnessed six or eight sorry jades. A Moldavian, with a mustache and a sheepskin cap, sitting astride one of them, incessantly shouted and cracked his whip, and his wretched animals ran on at a fairly sharp trot. If one of them began tp slacken its pace, he unharnessed it with terrible oaths and left it upon the road, little caring what might be its fate. On the return journey he was sure to find it in the same place, quietly grazing upon the green steppe. It not unfrequently happened that a traveler, starting from one station with eight horses, arrived at the next with a pair only. It used to be so about fifteen years ago. Nowadays in Russianized Bessarabia they have adopted Russian harness and the Russian

telega.

Such a

caruta

stood at the gate of the prison in the year 1821, toward the end of the month of September. Jewesses who wore drooping sleeves and loose slippers, Arnauts in their ragged and picturesque attire, well-pro- portioned Moldavian women with black-eyed children in their arms, surrounded the

caruta.

The men preserved silence; the women were eagerly expecting something.

The gate opened, and several police officers stepped out into the street; behind them came two soldiers leading the fettered Kirdjali.

He seemed about thirty years of age. The features of his swarthy face were regular and harsh. He was tall, broad-shouldered, and seemed endowed with unusual physical strength. A variegated turban covered the side of his head, and a broad sash encircled his slender waist. A dolman of thick, dark-blue cloth, a shirt, its broad folds falling below the knee, and handsome slippers composed the remainder of his costume. His look was proud and calm....

One of the officials, a red-faced old man in a faded uniform, on which dangled three buttons, pinched with a pair of pewter spectacles the purple knob that served him for a nose, unfolded a paper, and began to read nasally in the Moldavian tongue. From time to time he glanced haughtily at the fettered Kirdjali, to whom apparently the paper referred. Kirdjali listened to him attentively. The official finished his reading, folded up the paper and shouted sternly at the people, ordering them to make way and the

caruta

to be driven up. Then Kirdjali turned to him and said a few words to him in Moldavian; his voice trembled, his countenance changed, he burst into tears and fell at the feet of the police official, clanking his fetters. The police official, terrified, started back; the soldiers were about to raise Kirdjali, but he rose up himself, gathered up his chains, stepped into the

caruta

and cried: “Drive on!” A gendarme took a seat beside him, the Moldavian cracked his whip, and the

caruta

rolled away.

“What did Kirdjali say to you?” asked the young official of the police officer.

“He asked me,” replied the police officer, smiling, “to look after his wife and child, who live not far from Kilia, in a Bulgarian village: he is afraid that they may suffer through him. Foolish fellow!”

The young official’s story affected me deeply. I was sorry for poor Kirdjali. For a long time I knew nothing of his fate. Some years later I met the young official. We began to talk about the past.

“What about your friend Kirdjali?” I asked. “Do you know what became of him?”

“To be sure I do,” he replied, and related to me the following.

Kirdjali, having been brought to Jassy, was taken before the Pasha, who condemned him to be impaled. The execution was deferred till some holiday. In the meantime he was confined in jail.

The prisoner was guarded by seven Turks (simple people, and at heart as much brigands as Kirdjali himself); they respected him and, like all Orientals, listened with avidity to his strange stories.

Between the guards and the prisoner an intimate acquaintance sprang up. One day Kirdjali said to them: “Brothers! my hour is near. Nobody can escape his fate. I shall soon part from you. I should like to leave you something in remembrance of me.”

The Turks pricked up their ears.

“Brothers,” continued Kirdjali, “three years ago, when I was engaged in plundering along with the late Milchaelaki, we buried on the steppes, not far from Jassy, a kettle filled with coins. Evidently, neither I nor he will make use of the hoard. Be it so; take it for yourselves and divide it in a friendly manner.”

The Turks almost took leave of their senses. The question was, how were they to find the precious spot? They thought and thought and resolved that Kirdjali himself should conduct them to the place.

Night came on. The Turks removed the irons from the feet of the prisoner, tied his hands with a rope, and, leaving the town, set out with him for the steppe.

Kirdjali led them, walking steadily in one direction from mound to mound. They walked on for a long time. At last Kirdjali stopped near a broad stone, measured twelve paces toward the south, stamped and said: “Here.”

The Turks began to make their arrangements. Four of them took out their yataghans and commenced digging. Three remained on guard. Kirdjali sat down on the stone and watched them at their work.

“Well, how much longer are you going to be?” he asked; “haven’t you come to it?”

“Not yet,” replied the Turks, and they worked away with such ardor, that the perspiration rolled from them in great drops.

Kirdjali began to show signs of impatience.

“What people!” he exclaimed: “they do not even know how to dig decently. I should have finished the whole business in a couple of minutes. Children! untie my hands and give me a yataghan.”

The Turks reflected and began to take counsel together. “What harm would there be?” reasoned they. “Let us untie his hands and give him a yataghan. He is only one, we are seven.”

And the Turks untied his hands and gave him a yataghan.

At last Kirdjali was free and armed. What must he have felt at that moment!... He began digging quickly, the guards helping him.... Suddenly he plunged his yataghan into one of them, and, leaving the blade in his breast, he snatched from his belt a couple of pistols.

The remaining six, seeing Kirdjali armed with two pistols, ran off.

Kirdjali is now operating near Jassy. Not long ago he wrote to the Governor, demanding from him five thousand leus, and threatening, should the money not be forthcoming, to set fire to Jassy and to get at the Governor himself. The five thousand were delivered to him!

Such is Kirdjali!

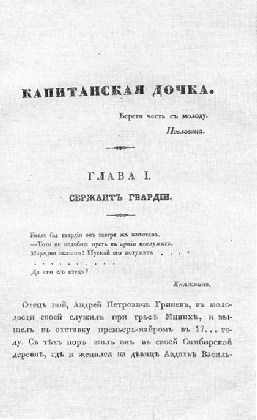

THE CAPTAIN’S DAUGHTER

Translated by Milne Home

This historical novella was first published in 1836 in the fourth issue of the literary journal

Sovremennik

. It is a romanticised account of Pugachev’s Rebellion in 1773-1774, which was the principal revolt in a series of popular rebellions that took place in Russia after Catherine II seized power in 1762. It began as an organised insurrection of Yaik Cossacks headed by Yemelyan Pugachev, a disaffected ex-lieutenant of the Russian Imperial army, against a background of profound peasant unrest and war with the Ottoman Empire.

The narrative introduces Pyotr Andreyich Grinyov as the only surviving child of a retired army officer. When Pyotr turns 17, his father sends him into military service in Orenburg. En route Pyotr gets lost in a blizzard, but is rescued by a mysterious man. As a token of his gratitude, Pyotr gives the guide his hareskin jacket.

The first page of the novella’s serialisation

CONTENTS

THE CAPTAIN’S DAUGHTER — OMITTED CHAPTER

Yemelyan Ivanovich Pugachov (1742-1775)

CHAPTER I.

SERGEANT OF THE GUARDS.

My father, Andréj Petróvitch Grineff, after serving in his youth under Count Münich, had retired in 17 — with the rank of senior major. Since that time he had always lived on his estate in the district of Simbirsk, where he married Avdotia, the eldest daughter of a poor gentleman in the neighbourhood. Of the nine children born of this union I alone survived; all my brothers and sisters died young. I had been enrolled as sergeant in the Séménofsky regiment by favour of the major of the Guard, Prince Banojik, our near relation. I was supposed to be away on leave till my education was finished. At that time we were brought up in another manner than is usual now.