World Order (23 page)

Authors: Henry Kissinger

The issue of peace in the Middle East has, in recent years, focused on the highly technical subject of nuclear weapons in Iran. There is no shortcut around the imperative of preventing their appearance. But it is well to recall periods when other seemingly intractable crises in the Middle East were given a new dimension by fortitude and vision.

Between 1967 and 1973, there had been two Arab-Israeli wars, two American military alerts, an invasion of Jordan by Syria, a massive American airlift into a war zone, multiple hijackings of airliners, and the breaking of diplomatic relations with the United States by most Arab countries. Yet it was followed by a peace process that yielded

three Egyptian-Israeli agreements (culminating in a peace treaty in 1979); a disengagement agreement with Syria in 1974 (which has lasted four decades, despite the Syrian civil war); the Madrid Conference in 1991, which restarted the peace process; the Oslo agreement between the PLO and Israel in 1993; and a peace treaty between Jordan and Israel in 1994.

These goals were reached because three conditions were met: an active American policy; the thwarting of designs seeking to establish a regional order by imposing universalist principles through violence; and the emergence of leaders with a vision of peace.

Two events in my experience symbolize that vision. In 1981, during his last visit to Washington, President Sadat invited me to come to Egypt the following spring for the celebration when the Sinai Peninsula would be returned to Egypt by Israel. Then he paused for a moment and said, “Don’t come for the celebration—it would be too hurtful to Israel. Come six months later, and you and I will drive to the top of Mount Sinai together, where I plan to build a mosque, a church, and a synagogue, to symbolize the need for peace.”

Yitzhak Rabin, once chief of staff of the Israeli army, was Prime Minister during the first political agreement ever between Israel and Egypt in 1975, and then again when he and former Defense Minister, now Foreign Minister, Shimon Peres negotiated a peace agreement with Jordan in 1994. On the occasion of the Israeli-Jordanian peace agreement, in July 1994 Rabin spoke at a joint session of the U.S. Congress together with King Hussein of Jordan:

Today we are embarking

on a battle which has no dead and no wounded, no blood and no anguish. This is the only battle which is a pleasure to wage: the battle of peace …In the Bible, our Book of Books, peace is mentioned in its various idioms, two hundred and thirty-seven times. In the

Bible, from which we draw our values and our strength, in the Book of Jeremiah, we find a lamentation for Rachel the Matriarch. It reads:“Refrain your voice from weeping, and your eyes from tears: for their work shall be rewarded, says the Lord.”

I will not refrain from weeping for those who are gone. But on this summer day in Washington, far from home, we sense that our work will be rewarded, as the Prophet foretold.

Both Sadat and Rabin were assassinated. But their achievements and inspiration are inextinguishable.

Once again, doctrines of violent intimidation challenge the hopes for world order. But when they are thwarted—and nothing less will do—there may come a moment similar to what led to the breakthroughs recounted here, when vision overcame reality.

CHAPTER 5

The Multiplicity of Asia

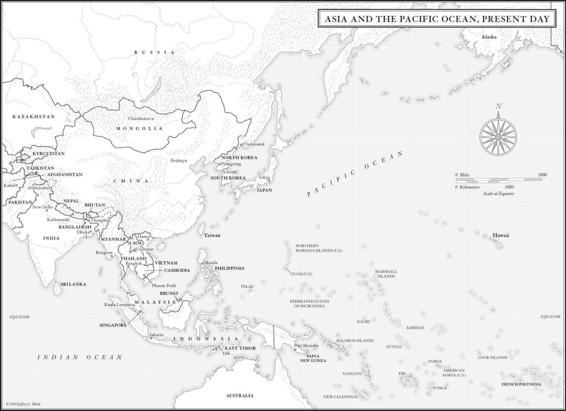

The term “Asia” ascribes a deceptive coherence to a disparate region.

Until the arrival

of modern Western powers, no Asian language had a word for “Asia”; none of the peoples of what are now Asia’s nearly fifty sovereign states conceived of themselves as inhabiting a single “continent” or region requiring solidarity with all the others. As “the East,” it has never been clearly parallel to “the West.” There has been no common religion, not even one splintered into different branches as is Christianity in the West. Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity all thrive in different parts of Asia. There is no memory of a common empire comparable to that of Rome. Across Northeast, East, Southeast, South, and Central Asia, prevailing major ethnic, linguistic, religious, social, and cultural differences have been deepened, often bitterly, by the wars of modern history.

The political and economic map of Asia illustrates the region’s

complex tapestry. It comprises industrially and technologically advanced countries in Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Singapore, with economies and standards of living rivaling those of Europe; three countries of continental scale in China, India, and Russia; two large archipelagoes (in addition to Japan), the Philippines and Indonesia, composed of thousands of islands and standing astride the main sea-lanes; three ancient nations with populations approximating those of France or Italy in Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar; huge Australia and pastoral New Zealand, with largely European-descended populations; and North Korea, a Stalinist family dictatorship bereft of industry and technology except for a nuclear weapons program. A large Muslim-majority population prevails across Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Indonesia, and sizeable Muslim minorities exist in India, China, Myanmar, Thailand, and the Philippines.

The global order during the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century was predominantly European, designed to maintain a rough balance of power between the major European countries. Outside their own continent, the European states built colonies and justified their actions under various versions of their so-called civilizing mission. From the perspective of the twenty-first century, in which Asian nations are rising in wealth, power, and confidence, it may seem improbable that colonialism gained such force or that its institutions were treated as a normal mechanism of international life. Material factors alone cannot explain it; a sense of mission and intangible psychological momentum also played a role.

The pamphlets and treatises of the colonial powers from the dawn of the twentieth century reveal a remarkable arrogance, to the effect that they were entitled to shape a world order by their maxims. Accounts of China or India condescendingly defined a European mission to educate traditional cultures to higher levels of civilization. European

administrators with relatively small staffs redrew the borders of ancient nations, oblivious that this might be an abnormal, unwelcome, or illegitimate development.

At the dawn of what is now called the modern age in the fifteenth century, a confident, fractious, territorially divided West had set sail to reconnoiter the globe and to improve, exploit, and “civilize” the lands it came upon. It impressed upon the peoples it encountered views of religion, science, commerce, governance, and diplomacy shaped by the Western historical experience, which it took to be the capstone of human achievement.

The West expanded with the familiar hallmarks of colonialism—avariciousness, cultural chauvinism, lust for glory. But it is also true that its better elements tried to lead a kind of global tutorial in an intellectual method that encouraged skepticism and a body of political and diplomatic practices ultimately including democracy. It all but ensured that, after long periods of subjugation, the colonized peoples would eventually demand—and achieve—self-determination. Even during their most brutal depredations, the expansionist powers put forth, especially in Britain, a vision that at some point conquered peoples would begin to participate in the fruits of a common global system. Finally recoiling from the sordid practice of slavery, the West produced what no other slaveholding civilization had: a global abolition movement based on a conviction of common humanity and the inherent dignity of the individual. Britain, rejecting its previous embrace of the despicable trade, took the lead in enforcing a new norm of human dignity, abolishing slavery in its empire and interdicting slave-trading ships on the high seas. The distinctive combination of overbearing conduct, technological prowess, idealistic humanitarianism, and revolutionary intellectual ferment proved one of the shaping factors of the modern world.

With the exception of Japan, Asia was a victim of the international order imposed by colonialism, not an actor in it. Thailand sustained its

independence but, unlike Japan, was too weak to participate in the balance of power as a system of regional order. China’s size prevented it from full colonization, but it lost control over key aspects of its domestic affairs. Until the end of World War II, most of Asia conducted its policies as an adjunct of European powers or, in the case of the Philippines, of the United States. The conditions for Westphalian-style diplomacy only began to emerge with the decolonization that followed the devastation of the European order by two world wars.

The process of emancipation from the prevalent regional order was violent and bloody: the Chinese civil war (1927–49), the Korean War (1950–53), a Sino-Soviet confrontation (roughly 1955–80), revolutionary guerrilla insurgencies all across Southeast Asia, the Vietnam War (1961–75), four India-Pakistan wars (1947, 1965, 1971, and 1999), a Chinese-Indian war (1962), a Chinese-Vietnamese war (1979), and the depredations of the genocidal Khmer Rouge (1975–79).

After decades of war and revolutionary turmoil, Asia has transformed itself dramatically. The rise of the “Asian Tigers,” evident from 1970, involving Hong Kong, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand, brought prosperity and economic dynamism into view. Japan adopted democratic institutions and built an economy rivaling and in some cases surpassing those of Western nations. In 1979, China changed course and, under Deng Xiaoping, proclaimed a nonideological foreign policy and a policy of economic reforms that, continued and accelerated under his successors, have had a profound transformative effect on China and the world.

As these changes unfolded, national-interest-based foreign policy premised on Westphalian principles seemed to have prevailed in Asia. Unlike in the Middle East, where almost all the states are threatened by militant challenges to their legitimacy, in Asia the state is treated as the basic unit of international and domestic politics. The various nations emerging from the colonial period generally affirmed one another’s sovereignty and committed to noninterference in one another’s domestic affairs; they followed the norms of international organizations and built regional or interregional economic and social organizations. In this vein a top Chinese military official, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Deputy Chief of General Staff Qi Jianguo, wrote in a major January 2013 policy review that one of the primary challenges of the contemporary era is to uphold “

the basic principle of modern international relations

firmly established in the 1648 ‘Treaty of Westphalia,’ especially the principles of sovereignty and equality.”

Asia has emerged as among the Westphalian system’s most significant legacies: historic, and often historically antagonistic, peoples are organizing themselves as sovereign states and their states as regional groupings. In Asia, far more than in Europe, not to speak of the Middle East, the maxims of the Westphalian model of international order find their contemporary expression—including doctrines since questioned by many in the West as excessively focused on the national interest or insufficiently protective of human rights. Sovereignty, in many cases wrought only recently from colonial rule, is treated as having an absolute character. The goal of state policy is not to transcend the national interest—as in the fashionable concepts in Europe or the United States—but to pursue it energetically and with conviction. Every government dismisses foreign criticism of its internal practices as a symptom of just-surmounted colonial tutelage. Thus even when neighboring states’ domestic actions are perceived as excesses—as they have been, for example, in Myanmar—they are treated as an occasion for quiet diplomatic intercession, not overt pressure, much less forcible intervention.