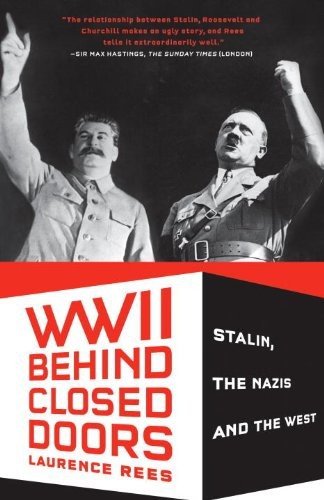

World War II Behind Closed Doors

Read World War II Behind Closed Doors Online

Authors: Laurence Rees

To Ian Kershaw

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE:

An Alliance in All but Name

CHAPTER TWO:

Decisive Moments

CHAPTER THREE:

Crisis of Faith

CHAPTER FOUR:

The Changing Wind

CHAPTER FIVE:

Dividing Europe

CHAPTER SIX:

The Iron Curtain

INTRODUCTION

When do you think the Second World War ended? In August 1945 after the surrender of the Japanese?

Well, it depends how you look at it. If you believe that the end of the war was supposed to have brought ‘freedom’ to the countries that had suffered under Nazi occupation, then for millions of people the war did not really end until the fall of Communism less than twenty years ago. In the summer of 1945 the people of Poland, of the Baltic states and a number of other countries in eastern Europe simply swapped the rule of one tyrant for that of another. It was in order to demonstrate this unpleasant reality that the presidents of both Estonia and Lithuania refused to visit Moscow in 2005 to participate in ‘celebrations’ marking the sixtieth anniversary of the ‘end of the war’ in Europe.

How did this injustice happen? That is one of the crucial questions this book attempts to answer. And it is a history that it has only been possible to tell since the fall of Communism. Not just because the hundred or so eye witnesses I met in the former Soviet Union and eastern Europe would never have been able to speak frankly under Communist rule, but also because key archival material that successive Soviet governments did all they could to hide has been made available only recently. The existence of these documents has allowed a true ‘behind-the-scenes’ history of the West's dealings with Stalin to be attempted. All of which means, I hope, that this book contains much that is new.

I have been lucky that the collapse of the Eastern Bloc has permitted this work. It was certainly something I could never have predicted would happen when I was taught the history of the Second World War at school back in the early 1970s. Then my history teacher got round the moral and political complexities of the Soviet Union's

1

participation in the war by the simple expedient of largely ignoring it. At the time, in the depths of the Cold War, that was how most people dealt with the awkward legacy of the West's relationship with Stalin. The focus was on the heroism of the Western Allies – on Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain and D-Day. None of which, of course, must be forgotten. But it is not the whole story.

Before the fall of Communism the role of the Soviet Union in the Second World War was, to a large extent, denied a proper place in our culture because it was easier than facing up to a variety of unpalatable truths. Did we, for example, really contribute to the terrible fate that in 1945 befell Poland, the very country we went to war to protect? Especially when we were taught that this was a war about confronting tyranny? And if, as we should, we do start asking ourselves these difficult questions, then we also have to pose some of the most uncomfortable of all. Was anyone in the West to blame in any way for what happened at the end of the war? What about the great heroes of British and American history, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt?

Paradoxically, the best way to attempt an answer to all this is by focusing on someone else entirely – Joseph Stalin. Whilst this is a book that is fundamentally about relationships, it is Stalin who dominates the work. And a real insight into the Soviet leader's attitude to the war is gained by examining his behaviour immediately before his alliance with the West. This period, of the Nazi-Soviet pact between 1939 and 1941, has been largely ignored in the popular consciousness. It was certainly ignored in the post-war Soviet Union. I remember asking one Russian after the fall of the Berlin Wall: ‘How was the Nazi-Soviet pact taught when you were in school during the Soviet era? Wasn't it a tricky piece of history to explain away?’ He smiled in response. ‘Oh, no’, he said, ‘not tricky at all. You see, I didn't learn there had ever been a Nazi-Soviet pact until after 1990 and the collapse of the Soviet Union’.

Stalin's relationship with the Nazis is a vital insight into the kind of person he was; because, at least in the early days of the relationship, he got on perfectly well with them. The Soviet Communists and the German Nazis had a lot in common – not ideologically, of course, but in practical terms. Each of them respected the importance of raw power. And each of them despised the values that a man like Franklin Roosevelt held most dear, such as freedom of speech and the rule of law. As a consequence, we see Stalin at his most relaxed in one of the first encounters in the book, carving up Europe with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Nazi Foreign Minister. The Soviet leader was never to attain such a moment of mutual interest and understanding at any point in his relationship with Churchill and Roosevelt.

It is also important to understand the way in which the Soviets ran their occupation of eastern Poland between 1939 and 1941. That is because many of the injustices that were to occur in parts of occupied eastern Europe at the end of the war were broadly similar to those the Soviets had previously committed in eastern Poland – the torture, the arbitrary arrests, the deportations, the sham elections and the murders. What the earlier Soviet occupation of eastern Poland demonstrates is that the fundamental nature of Stalinism was obvious from the start.

So it isn't that Churchill and Roosevelt were unaware in the beginning of the kind of regime they were dealing with. Neither of them was initially enthusiastic about the forced alliance with Stalin following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Churchill considered it akin to a pact with ‘the Devil’, and Roosevelt, even though the United States was still officially neutral in the summer of 1941, was careful in his first statement after the Nazi invasion to condemn the Soviets for their previous abuses.

How the British and Americans moved from that moment of justified scepticism about Stalin to the point immediately after the Yalta Conference in February 1945 when they stated, with apparent sincerity, that Stalin ‘meant well to the world’ and was ‘reasonable and sensible’, is the meat of this book. And the answer to why Churchill and Roosevelt publicly altered their position about Stalin and the Soviet Union doesn't lie just in understanding the massive geo-political issues that were at stake in the war – and crucially the effect on the West of the successful Soviet fight-back against the Nazis – but also takes us into the realm of personal emotions. Both Churchill and Roosevelt had gigantic egos and both of them liked to dominate the room. And both of them liked the sound of their own voices. Stalin wasn't like that at all. He was a watcher – an aggressive listener.

It was no accident that it took two highly intelligent functionaries on the British side – Sir Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under Secretary at the Foreign Office, and Lord Alanbrooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff – to spot Stalin's gifts most accurately. They saw him not as a politician playing to the crowd and awash with his own rhetoric, but more like a bureaucrat – a practical man who got things done. As Cadogan confided in his diary at Yalta: ‘I must say I think Uncle Joe [Stalin] much the most impressive of the three men. He is very quiet and restrained…. The President flapped about and the PM boomed, but Joe just sat taking it all in and being rather amused. When he did chip in, he never used a superfluous word and spoke very much to the point’.

2

Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke ‘formed a very high idea of his [Stalin's] ability, force of character and shrewdness’.

3

In particular, Alanbrooke was impressed that Stalin ‘displayed an astounding knowledge of technical railway details’.

4

No one would ever accuse Churchill or Roosevelt – those biggest of ‘big picture’ men – of having ‘an astounding knowledge of technical railway details’. And it was Alanbrooke who spotted early on what was to be the crux of the final problem between Stalin and Churchill: ‘Stalin is a realist if ever there was one’, he wrote in his diary, ‘facts only count with him… [Churchill] appealed to sentiments in Stalin which I do not think exist there’.

5

As one historian has put it, the Western leaders at the end of the war ‘were not dealing with a normal, everyday, run-of-the-mill, statesmanlike head of government. They confronted instead a psychologically disturbed but fully functional and highly intelligent dictator who had projected his own personality not only onto those around him but onto an entire nation and had thereby with catastrophic results, remade it in his image’.

6

One of the problems was that Stalin in person was very different from the image of Stalin the tyrant. Anthony Eden, one of the first Western politicians to spend time with Stalin in Moscow during the war, remarked on his return that he had tried hard to imagine the Soviet leader ‘dripping with the blood of his opponents and rivals, but somehow the picture wouldn't fit’.

7

But Roosevelt and Churchill were sophisticated politicians and it is wrong to suppose that they were simply duped by Stalin. No, something altogether more interesting – and more complicated – takes place in this history. Roosevelt and Churchill wanted to win the war at the least possible cost to their own respective countries – in both human and financial terms. Keeping Stalin ‘on side’, particularly during the years before D-Day when the Soviets believed they were fighting the war almost on their own, was a difficult business and required, as Roosevelt would have put it, ‘careful handling’. As a result, behind closed doors the Western leaders felt it necessary to make hard political compromises. One of them was to promote propaganda that painted a rosy picture of the Soviet leader; another was deliberately to suppress material that told the truth about both Stalin and the nature of the Soviet regime. In the process the Western leaders might easily, for the sake of convenience, have felt they had to ‘distort the normal and healthy operation’ of their ‘intellectual and moral judgements’ as one senior British diplomat was memorably to put it during the war.

8

However, this isn't just a ‘top-down’ history, examining the mentality and beliefs of the elite. I felt from the first that it was also important to show in human terms the impact of the decisions taken by Stalin and the Western Allies behind closed doors. And so in the course of writing this book I travelled across the former Soviet Union and Soviet-dominated eastern Europe and asked people who had lived through this testing time to tell their stories.

Uncovering this history was a strange and sometimes emotional experience. And – at least to me – it all seemed surprisingly fresh and relevant. I felt this most strongly standing in the leafy square by the opera house in Lviv. This elegant city had started the twentieth century in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, become part of Poland after the First World War, then part of the Soviet Union between 1939 and 1941, then part of the Nazi Empire until 1944, then part of the Soviet Union again, until finally in 1991 it became part of an independent Ukraine. At various times in the last hundred years the city has been called Lemberg, Lvov, Lwów and Lviv There was not one group of citizens I met there who had not at one time or another suffered because of who they were. Catholic or Jew, Ukrainian, Russian or Pole, they had all faced persecution in the end. It was the Nazis, of course, who operated the most infamous and murderous policy of persecution against the Jews of the city, but we are apt to forget that such was the change and turmoil in this part of central Europe that ultimately few non-Jews escaped suffering of one kind or another either.

I was fortunate to have a chance to meet these witnesses to history – all the more so since in the near future there will be no one left alive who personally experienced the war. And after having spent so much time with these veterans from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc I am left with an overwhelming sense of the importance of recovering their history as part of our own. Our nations were all in the war together. And we owe it to them, and to ourselves, to face up to the consequences of that truth.

Other books

Chasing the Skip by Patterson, Janci

Radio Belly by Buffy Cram

The People in the Park by Margaree King Mitchell

A Matter of Honor by Gimpel, Ann

Caller of Light by Tj Shaw

I'm Your Bully (Bully Book Series 1) by Andrea Tyse

Forever Hers by Walters, Ednah

Saving Dancer (Savage Brothers MC Book 2) by Marie, Jordan

Gilt by Wilson, JL

Mr. James: A Forbidden Romance by Legend, Lacey