Authors: Joe Haldeman

Worlds Apart (29 page)

We watched the sun set on Los Angeles and rise over London. Then on to midmorning in New York, one of the few places with a large number of people. You could see them on the sidewalks. Some of the slidewalks were actually rolling again.

Evy has never been to Earth, of course. Of the ten thousand people aboard this crate, only a few hundred have.

I guess writing that down is a tacit admission that I’m writing this for other people to read. But not for a long time. Hello, reader, up there in the future. I’m dead now. And will feel worse in the morning.

I think it’s a good thing this starship is automated. Many key personnel are functioning at a low level of efficiency, if functioning at all. Including yours truly, Entertainment Director. The entertainment program for tomorrow, this morning rather, will be quiet music and contemplation of the sequelae of overindulgence.

If I’d drunk less or more I would be sleepy. At this level I’m edgy, and too stimulated to read or rest and too stupid to stop writing. At least by typing it out on the machine, I can erase the evidence tomorrow. Unless Prime makes a copy. She’s everywhere.

Are you listening, Prime? No answer. So you’re a liar as well as a soulless machine.

Since this is indeed the first entry in the Diary of the Rest of My Life, which is of course true every time one makes any entry in a diary, I will include some background data for you generations yet unborn. Perhaps you are mumbling these words around a guttering fire in a cave on Epsilon, this starship a legend a million years gone to dust. Perhaps you are one of my husbands reading it tomorrow. You think I don’t know I don’t have any secrets. Hah. Marry computer experts and give up any hope of privacy. I saw John break Tulip Seven’s thumbprint code the day after she died. (He didn’t do it for any trivial reason; the tribunal wanted him to have her files scanned for evidence. She drank poison but it might have been murder. Nothing conclusive.)

As I was saying. Two days ago we left the planet Earth

forever. Actually what we left was the satellite world New New York, which has been orbiting the Earth since before my grandmother was born. The Earth itself has been a mess since 2085, as you must know or can read about somewhere else. Almost everybody killed in a war. I started to write “senseless” war. Do you have sensible ones, up there in the future? That’s something we never worked out, not to everyone’s satisfaction.

One reason the ten thousand of us are embarked on this one-way fling into the darkness is that Earth does seem to be recovering, and the next time they decide to Kill Everybody they might be more successful.

Another reason is that there doesn’t seem to be anyplace else to go. We could inhabit settlements on the Moon or Mars, or wherever, but they would just be extensions of New New; suburbs. This is the real thing. ’Bye, Mom. No turning back.

As a matter of fact, my mother isn’t aboard. Nor my sister. Just as glad Mother stayed back but wish she had let Joyce come along. Old enough to be a good companion and still young enough to renew things for you as she discovers them.

I guess two husbands and a wife comprise enough family for anyone. God knows how many cousins I have scattered around. When the Nabors line kicked my mother out it was a mutual see-you-in-hell parting, and as I was only five days old, I had not yet formed any lasting relationships. There are a few Scanlans aboard, my formal line family, but I feel more kinship with some of the food animals.

Oh yes, you generations yet unborn. You do know what a starship is, don’t you, mumbling around the guttering campfire? It is like a great bird with ten thousand people in its gullet and a matter/antimatter engine stuck up its huge birdy ass.

Up in the front, instead of a beak, there is a doughnut-shaped structure, with three spokes and a hub, which used to be Uchūden, a small world that also escaped destruction during the war, originally designed to be home for several hundred Japanese engineers. (Japan was an island nation on Earth, the most wealthy.) Now it functions as the control

center for all of ’Home, the civil government as well as the thrilling engineering stuff.

Behind Uchūden, or “sternward,” as they want us to say, are all the living quarters, offices, farms, factories, laboratories—you name it, even a market where you can spend all of your hard-earned fake money.

A simplified diagram of the ship would be six concentric cylinders, shells; the acreage per shell and apparent gravity increasing as the number goes down. Most people live and work on Shells 1, 2, and 3; the inner ones reserved for processes that require lower gravity, such as metallurgy and free-fall sex. There are also some living quarters up there for the elderly and infirm, such as my husband John Ogelby, who has an uncorrectable curvature of the spine that makes even three-quarters gee painful. He also has a lot of political pull (“friends in high places” has a strong literal meaning here) and so rates a rather large bedroom/office/galley combination on Shell 6. The family tends to gather there.

I’m writing this in my small office cubicle in Uchūden, which is by definition Shell 1. As perquisites of rank I do have a cot that folds down from the wall and an actual window to the outside—on the floor, of course. I can either watch the stars wheel by once each thirty-three seconds or flip on a revolving mirror that keeps the stars stationary for fifteen seconds at a time. I like to watch them roll.

That concentric-cylinder model is just a theoretical idealization. You’d go crazy, living in a metal hive like that. So the walls and ceilings are knocked down and conjoined in various ways to give a variety of volumes and lines of sight. Most people still spend a certain amount of time hopelessly lost, since only a few hundred of us lived here while it was being built, and have had time to get used to it. New New was laid out logically, the corridors a simple grid on each level, and it was impossible to get lost. ’Home is deliberately chaotic, even whimsical, and is supposed to be constantly changing. Only time will tell whether this will keep us sane or drive us mad.

Still, the longest line of sight is only a couple of hundred meters, looking across the park. It’s a good thing that

almost all of us grew up in satellite Worlds. Someone used to the wide open spaces of Earth would probably feel trapped by ’Home’s claustrophobic architecture. In most corridors, for obvious instance, the floor curves up in two directions, cut off by the low ceiling in twenty meters or less—a lot less, up in 5 and 6. Of course you can look out for zillions of light-years if you have a window like mine, but for some reason some people don’t find that relaxing.

Both of my husbands were born on Earth, but spent enough years in New New to have lost the need for long lines of sight; distant horizons.

I do miss horizons, vistas, from my three visits to Earth. The first couple of weeks I spent there I had a hard time adjusting to the long lines of sight, even though I was in New York City, which most groundhogs would consider crowded. I would look up from the sidewalk and see a building impossibly far away and lose my balance.

I remember flying over kilometer after kilometer of forest, ocean, farmland, city. The Pyramids and the Rockies and Angkor Wat and even Las Vegas. We live inside one of the largest structures ever built, surely the largest vehicle—but we’ll never

see

anything big for the rest of our lives.

At least Dan and John and I have memories. Evy and nine thousand others just moved from one hollow rock into a newer one. Maybe they’re the lucky ones, I have to say, conventionally. I wouldn’t trade places.

Well, the rigors of composition seem to have sobered and tired me enough for sleep. Fold up the keyboard and unfold the cot. If the gravity gives me trouble I can always rejoin the hamster pile upstairs.

Buy

Worlds Enough and Time

Now!

Joe Haldeman is a renowned American science fiction author whose works are heavily influenced by his experiences serving in the Vietnam War and his subsequent readjustment to civilian life.

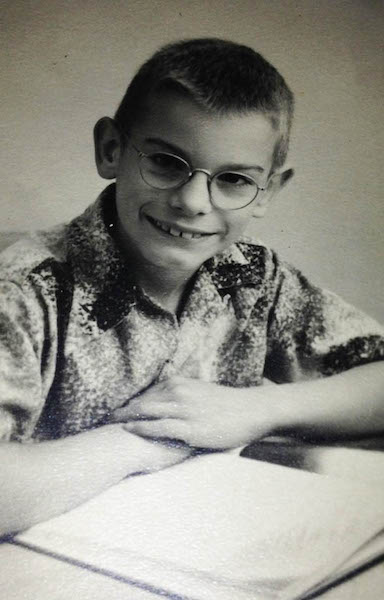

Haldeman was born on June 9, 1943, to Jack and Lorena Haldeman. His older brother was author Jack C. Haldeman II. Though born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Haldeman spent most of his youth in Anchorage, Alaska, and Bethesda, Maryland. He had a contented childhood, with a caring but distant father and a mother who devoted all her time and energy to both sons.

As a child, Haldeman was what might now be called a geek, happy at home with a pile of books and a jug of lemonade, earning money by telling stories and doing science experiments for the neighborhood kids. By the time he entered his teens, he had worked his way through numerous college books on chemistry and astronomy and had skimmed through the entire encyclopedia. He also owned a small reflecting telescope and spent most clear nights studying the stars and planets.

Fascinated by space, the young Haldeman wanted to be a “spaceman”—the term

astronaut

had not yet been coined—and carried this passion with him to the University of Maryland, from which he graduated in 1967 with a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy. By this time the United States was in the middle of the Vietnam War, and Haldeman was immediately drafted.

He spent one year in Vietnam as a combat engineer and earned a Purple Heart for severe wounds. Upon his return to the United States in 1969, during the thirty-day “compassionate leave” given to returning soldiers, Haldeman typed up his first two stories, written during a creative writing class in his last year of college, and sent them out to magazines. They both sold within weeks, and the second story was eventually adapted for an episode of

The Twilight Zone

. At this point, though, Haldeman was accepted into a graduate program in computer science at the University of Maryland. He spent one semester in school. He was also invited to attend the Milford Science Fiction Writers’ Conference—a rare honor for a novice writer.

In September of the same year, Haldeman wrote an outline and two chapters of

War Year

, a novel that would be based on the letters he had sent to his wife, Gay, from Vietnam. Two weeks later he had a major publishing contract. Mathematics was out of the picture for the near future.

Haldeman enrolled in the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he studied with luminary figures such as Vance Bourjaily, Raymond Carver, and Stanley Elkin, graduating in 1975 with a master of fine arts degree in creative writing. His most famous novel,

The Forever War

(1974), began as his MFA thesis and won him his first Hugo and Nebula Awards, as well as the Locus and Ditmar Awards.

Haldeman was now at his most productive, working on several projects at once. Arguably his largest-scale undertaking was the Worlds trilogy, consisting of

Worlds

(1981),

Worlds Apart

(1983), and

Worlds Enough and Time

(1992). Immediately before releasing the series’ last installment, however, Haldeman published his renowned novel

The Hemingway Hoax

(1990), which dealt with the experiences of combat soldiers in Vietnam. The novella version of the book won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards, a feat that Haldeman repeated with the publication of his next novel,

Forever Peace

(1997), which also won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel.

In 1983 Haldeman accepted an adjunct professorship in the writing program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He taught every fall semester, preferring to be a full-time writer for the remainder of the year. While at MIT he wrote

Forever Free

, the final book in his now-famous Forever War trilogy.

Haldeman has since written or edited more than a half-dozen books, with a second succession of titles being published in the early 2000s, including

The Coming

(2000),

Guardian

(2002),

Camouflage

(2004)—for which he won his fourth Nebula—and

The Old Twentieth

(2005). He also released the Marsbound trilogy, publishing the namesake title in 2008 and quickly following it with

Starbound

(2010) and

Earthbound

(2011).

A lifetime member and past president of the Science Fiction Writers of America, Haldeman was selected as its Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master for 2010. He was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2012.

After publishing his novel

Work Done for Hire

and retiring from MIT in 2014, Haldeman now lives in Gainesville, Florida, and plans to continue writing a novel every couple of years.

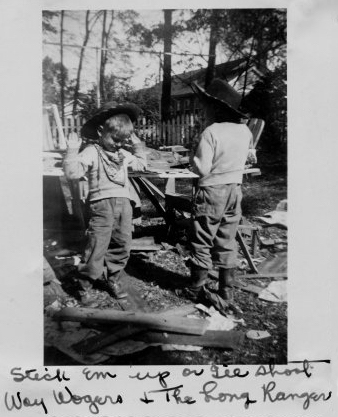

The author and his brother, Jack, around the year 1948. The image is captioned “Stick ’em up or I’ll shoot. Woy Wogers and the Long Ranger.”