Worlds (35 page)

Authors: Joe Haldeman

“I don’t think it’s too great. Harkness, Robert Harkness, claimed that we could keep a subject in the old isolation module, handle him completely by remote control. Knock him out to take samples and run tests, if that were necessary.”

“Damned complicated.”

“Yeah. And no way really to keep it secret. Guess I’d better call Markus again.”

Ahmed headed toward the spacesuit locker. “I’ll go set the girl’s arm. See whether the boy’s alive.”

“We can’t disinfect you again.”

“I can live in the suit for two days.” He looked at the cube. “But probably the kindest thing we could do for them is open the bay doors right now…if that’s the decision, let me know. I’ll give them something so they won’t feel it.”

“Okay.” Some of them went to help Ahmed get into his suit. Berrigan cleared the board and the control room was suddenly silent, without the little girl’s crying. She sat for a minute without typing anything, peering into the glowing cube, her lips moving slightly. O’Hara was quietly scrubbing the inside of her helmet.

“Marianne—you want to be in my shoes someday, on the Policy side?” O’Hara nodded. “Well, here’s a cute problem for you to think about.

“What Coordinators can or can’t do on their own is a vaguely defined mixture of statute, precedent, and common

sense. There’s no precedent for something like this, but since it so obviously involves the general welfare, it has to be put to referendum.

“I know we can isolate them adequately. The quarantine procedures we used on you people would be enough.” She tapped out a sequence and the cube showed the storage bay again. Ahmed was holding the girl’s hand, talking quietly.

“So what do you do if your people vote to make you a murderer?”

Charlie’s Will

Some of the grownups didn’t die.

Perhaps one in a hundred thousand suffered a peculiar dysfunction of the pituitary gland, which made the body manufacture an abnormal amount of GH, growth hormone. This prevented the normal aging process from triggering the virus. The side effects of the hormonal imbalance, though, could be severe. One was acromegaly, gigantism: people grew very tall, with large hands, feet, and heads. They were often mentally retarded.

The ones who raided pharmacies and hospitals to keep up their supply of the compensating hormone, NGH—these prudent ones died, as all adults did. The others lived, if the environment allowed it.

In many parts of the world the children killed them, or at least refused to care for them. In Charlie’s Country, which used to be Florida and Georgia, they were venerated. The more batty, the more respected, for madness was truth’s disguise.

5

Two percent of the population saved Coordinator Berrigan from having to commit murder. The vote, after twenty-four hours of debate, came to 51 percent in favor of trying to find the cure, 49 percent in favor of not taking any chances. (The juvenile vote, which was not binding, showed 82 percent of citizens under sixteen in favor of exterminating the children, or protecting New New, or spacing the groundhogs, depending on whose rhetoric you favored.)

O’Hara and the six others moved back into the tomato-and-cucumber paradise of Module 9B for a few weeks of appeasing their neighbors’ paranoia. O’Hara was bitter about it. Like every other sensible person, she knew that there was no slightest chance that any of them was carrying the plague. Berrigan claimed to enjoy the vacation. She did most of the work on the cube anyhow, and this way she didn’t have to go to lunch with people who were trying to sell her something.

The African boy never regained consciousness. Evidently his body had cushioned the girl during the fierce acceleration; his neck and back were broken. He died while they were setting up the isolation module, and they froze him for eventual autopsy.

The isolation module was a small sphere that had never been intended for use by human beings. It was a holding area for cuttings, seedlings, and livestock imported from Earth. If any sign of disease appeared, the stock would be consumed by fire and the ashes blown into space (once there was enough evidence for the insurance people). It was a tiny cage, and the little girl cried and babbled and refused to eat the strange food that robot arms offered her.

Nobody in New New spoke Bantu; Ahmed set about learning it. Within a week he was able to explain to the

girl approximately what had happened, and soon after, she reciprocated: she and her brother often went up there to play, not being afraid of high places or bones; it was especially fun since the older ones forbade it. She only dimly understood the rules of the game the older children were playing. They kept talking about a “brain devil” that would kill her if she didn’t behave, and she vaguely remembered that a cousin had died and they said that was why. But they said a lot of things that made no sense.

Her name was Insila. She and her brother had climbed up the emergency stairs to the cargo bay level, and had gone inside the spaceship while the door was open. When one of the forklifts came back, they hid in an empty locker. They came out when everything was quiet and dark, and tried to get the bay door open. Then there were noises again, and they ran back to the locker to hide. Then something knocked her out. When she woke up they were floating and her brother was hurt bad, and her arm wouldn’t work, and then Ahmed came in and helped her.

She wondered what would become of her. Ahmed tried to explain what the brain devil actually was, and what doctors were, and how they would try to cure her. He suspected that she didn’t believe a word of it. He didn’t tell her that in all likelihood she would spend the next ten years floating in that cage, with occasional forays into unconsciousness, until whatever it was did whatever it did, and she would go insane and die. And be sliced up, analyzed, and incinerated, like her brother. She knew he was dead but never once asked what had happened to him.

Buy

Worlds Apart

Now!

Joe Haldeman is a renowned American science fiction author whose works are heavily influenced by his experiences serving in the Vietnam War and his subsequent readjustment to civilian life.

Haldeman was born on June 9, 1943, to Jack and Lorena Haldeman. His older brother was author Jack C. Haldeman II. Though born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Haldeman spent most of his youth in Anchorage, Alaska, and Bethesda, Maryland. He had a contented childhood, with a caring but distant father and a mother who devoted all her time and energy to both sons.

As a child, Haldeman was what might now be called a geek, happy at home with a pile of books and a jug of lemonade, earning money by telling stories and doing science experiments for the neighborhood kids. By the time he entered his teens, he had worked his way through numerous college books on chemistry and astronomy and had skimmed through the entire encyclopedia. He also owned a small reflecting telescope and spent most clear nights studying the stars and planets.

Fascinated by space, the young Haldeman wanted to be a “spaceman”—the term

astronaut

had not yet been coined—and carried this passion with him to the University of Maryland, from which he graduated in 1967 with a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy. By this time the United States was in the middle of the Vietnam War, and Haldeman was immediately drafted.

He spent one year in Vietnam as a combat engineer and earned a Purple Heart for severe wounds. Upon his return to the United States in 1969, during the thirty-day “compassionate leave” given to returning soldiers, Haldeman typed up his first two stories, written during a creative writing class in his last year of college, and sent them out to magazines. They both sold within weeks, and the second story was eventually adapted for an episode of

The Twilight Zone

. At this point, though, Haldeman was accepted into a graduate program in computer science at the University of Maryland. He spent one semester in school. He was also invited to attend the Milford Science Fiction Writers’ Conference—a rare honor for a novice writer.

In September of the same year, Haldeman wrote an outline and two chapters of

War Year

, a novel that would be based on the letters he had sent to his wife, Gay, from Vietnam. Two weeks later he had a major publishing contract. Mathematics was out of the picture for the near future.

Haldeman enrolled in the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he studied with luminary figures such as Vance Bourjaily, Raymond Carver, and Stanley Elkin, graduating in 1975 with a master of fine arts degree in creative writing. His most famous novel,

The Forever War

(1974), began as his MFA thesis and won him his first Hugo and Nebula Awards, as well as the Locus and Ditmar Awards.

Haldeman was now at his most productive, working on several projects at once. Arguably his largest-scale undertaking was the Worlds trilogy, consisting of

Worlds

(1981),

Worlds Apart

(1983), and

Worlds Enough and Time

(1992). Immediately before releasing the series’ last installment, however, Haldeman published his renowned novel

The Hemingway Hoax

(1990), which dealt with the experiences of combat soldiers in Vietnam. The novella version of the book won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards, a feat that Haldeman repeated with the publication of his next novel,

Forever Peace

(1997), which also won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel.

In 1983 Haldeman accepted an adjunct professorship in the writing program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He taught every fall semester, preferring to be a full-time writer for the remainder of the year. While at MIT he wrote

Forever Free

, the final book in his now-famous Forever War trilogy.

Haldeman has since written or edited more than a half-dozen books, with a second succession of titles being published in the early 2000s, including

The Coming

(2000),

Guardian

(2002),

Camouflage

(2004)—for which he won his fourth Nebula—and

The Old Twentieth

(2005). He also released the Marsbound trilogy, publishing the namesake title in 2008 and quickly following it with

Starbound

(2010) and

Earthbound

(2011).

A lifetime member and past president of the Science Fiction Writers of America, Haldeman was selected as its Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master for 2010. He was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2012.

After publishing his novel

Work Done for Hire

and retiring from MIT in 2014, Haldeman now lives in Gainesville, Florida, and plans to continue writing a novel every couple of years.

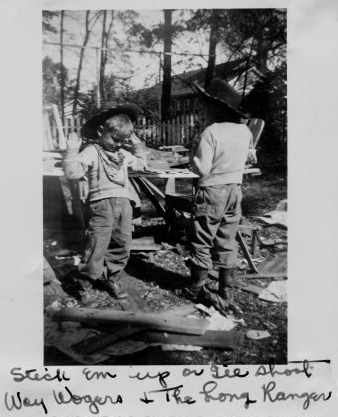

The author and his brother, Jack, around the year 1948. The image is captioned “Stick ’em up or I’ll shoot. Woy Wogers and the Long Ranger.”

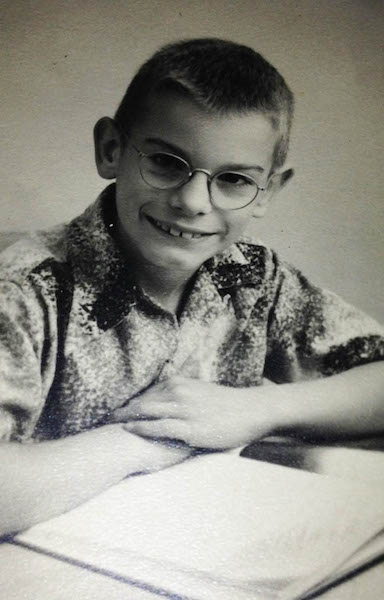

Haldeman in third grade, the year he discovered science fiction.

Haldeman’s mother, Lorena, and a bear cub in Alaska around the year 1950.