You Will Know Me (2 page)

Authors: Abbott,Megan

Strangely, in part it was because of Devon. They shared so much in sharing her, her endeavor. She held them together, tightly.

Â

The morning after the party, Katie turned over and saw a violet smear on her pillowcase.

It took her a while to remember. After midnight, trundling Drew across the ice-ribbed parking lot and into the car, Eric still inside, trying to find Devon, saying final good-byes.

A tap on the shoulder and it was Ryan Beck again. Smiling that chipped-front-tooth smile.

“Devon's?” he asked. Dangling from his open palm was a familiar lei, purple and green orchids, petals shredded. “I found it over by the dumpsters.”

“What a shame,” Katie said, feeling it more sharply than she should, blaming it on the rum. “Thanks.”

He draped it over her head, its dampness tickling her, his sneakers nearly slipping on the rimy concrete. A squeak, a skid. Later, she would wonder if he'd slipped like that on Ash Road seconds before he died, his sneakers on the sandy gravel as the headlights came.

“Careful,” Katie said, a catch in her voice. “It's not safe.”

“Nothing ever is,” he said, winking, his white tee glowing under the lights, backing away, into the dark of the emptying lot. “Good night, Mrs. Knox. Good night.”

“The eyes of a young girl can tell everything. And I always look in their eyes. There I can see if I will have a champion.”

âNeshka Robeva, gymnast and coach

If she ever had to talk about it, which she never would, Katie would have to go back, back years before it happened. Before Coach T. and Hailey and Ryan Beck. Back before Devon was born, when there were only two Knoxes, neither of whom knew a tuck from a salto or what you called that glossy egg-shaped platform in the center of the room, the vault that would change their lives.

And Katie would tell it in three parts.

The Foot.

The Fall.

The Pit.

You could only begin to understand what happened, and why, if you understood these three things.

And Devon's talent. Because that had been there from the beginning, maybe even before the beginning.

In proud-parent moments, of which there were too many to count, she and Eric would talk about feeling Devon in the womb, her body arching and minnowing and promising itself to them both.

Soon, it turned to kicking. Kicking with such vigor that, one night, Katie woke to a popping sound and, breathless, keeled over in pain. Eric stared helplessly at the way her stomach seemed to spasm with alien horrors.

What was inside her, they wondered, her rib poking over her sternum, dislocated while she slept.

It was no alien, but it was something extraordinary.

It was Devon, a marvel, a girl wonder, a prodigy, a star.

Devon, kicking her way out. Out, out, out.

And they had made her.

And, in some ways, she had made them.

Â

For years, Katie would touch the spot the rib had poked, as if she could still feel the tender lump. It was reassuring somehow. It reminded her that it had always been there, that force in Devon, that fire.

Like that line in that poem, the one she'd read in school, a lifetime ago. Back when life felt so cramped and small, when she never thought anything so grand could ever happen.

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower.

Â

“She's been doing it since she was three? How is that even possible?”

That's what other people, never gym people, always said. Making private judgments, unspoken charges of helicopter parenting, unmet maternal, or paternal, ambitions, Olympic dreams. No one ever believed Katie and Eric had never cared about sports, or even competition. Eric had played high-school baseball, indifferently. Katie had never been athletic at all, devoting her adolescence to art class and boys and sneaking off to see bands, the vestige of which was the

Fight Like a Grrrl

tattoo snaking around her left thigh.

“My three-year-old just wanted to play,” they'd say smugly. “We just let her play.”

As if it had ever been a choice, or a decision.

“It started as play,” Eric always told people. “It started with the trampoline.”

Then he'd tell them how, one long Sunday, he'd installed it in the yard, leaning over the auger rented from the hardware store, a pile of chicken wire, empty beer bottles at his feet.

The trampoline was the better story, an easier one, but it wasn't the truth.

Because the trampoline came after the accident, came after the Foot. And the accident was how it truly began. How that force in her found its fuse.

Three-year-old Devon, barefoot, running across the lawn to Daddy.

Her foot sliding on a grass mound, she stumbled into their idling, rust-eaten lawn mower, her foot so tiny it slipped behind the blade guard, the steel shearing off two toes and a squeak of soft foot flesh.

A few feet away, face white with panic, Eric slid to his knees beside her and somehow managed to pluck both toes from the grass.

Packed in ice, they looked like pink peas and Katie held them in her hands as Eric drove with careering ferocity the six miles to the hospital where doctors tried (but failed) to reattach them, like stringing beads, Devon's face blue and wet.

“It could have been worse,” their pediatrician, Dr. Yossarian, told them later. “Sometimes with the riding mowers, the whole foot pops off.” And he made an appalling pucker sound with his mouth.

“But what can we do?” Eric asked, even as Dr. Yossarian assured them Devon would be fine. “There must be something.”

So Dr. Yossarian suggested kiddie soccer, or ice-skating, or tumbling, something.

“It'll help with balance,” he said.

In years to come, this would feel like a moment of shimmering predestiny, in the same way everything about Devon's life eventually came to feel mythic within the family. Fate, destiny, retroactivated by a Sears Craftsman.

Â

That fall, Katie drove Devon to the Tumbleangels Gym on Old Taylor Road and signed them both up for Mommy & Me Movers & Shakers.

“At first, she'll be overly cautious,” Dr. Yossarian warned, “but try to push her.”

Except it was just the opposite. Within a few weeks, Devon was forward- and backward-rolling. Next came chin-ups, handstands, cartwheels as accomplished as those of girls twice her age.

The

Human

Rubber Band

, Katie called her.

Supergirl

, Eric called her.

Monkey-bar superstar!

And, in some mysterious way, it was as if the foot were helping her.

Frankenfoot

, Katie dubbed it. Making it their private joke.

Show Mommy how you work that Frankenfoot.

By the end of her first month, Devon had graduated to Tiny Tumblerz, and within a year, Devon was the gym's VIP, her cubbyhole sprayed silver and festooned with sticker stars.

Watching her on the practice beam, Katie would think,

This piece of wood is four inches wide, two feet in the air. Four inches. And I'm going to let my daughter plant her dimpled feet on that and do kicks and dips?

“Do the O,” the other girls would say, cheering as Devon arched her back from a handstand until her tiny bottom touched the top of her head. Every now and then, Eric would lift her up in the air to see if her backbone was really there.

Prodigy

, Katie whispered in her most private thoughts but never said aloud. Eric said it. He said it a lot.

And so Eric installed the trampoline.

Hours, days devoted to making the yard ready for her talent, laying thick mats like dominoes. Just as he would eventually do in the basement, hanging a pull-up bar, scraping the concrete bumps off the floor, covering it with panel mats and carpet remnants, wrapping foam around the ceiling posts. For Devon.

Â

And so gymnastics became the center, the mighty spine of everything for them.

Devon turning five, six, seven, thousands of hours driving to and from the gym, to and from the meets, a half a dozen emergency-room visits for the broken toe, knee sprain, elbow popping on the mat, seven stiches after Devon fell from the bars and bit through her tongue.

And the money. Gym tuition, meet fees, equipment, travel, booster fees. She and Eric had stopped counting, gradually becoming used to swelling credit-card debt.

Then, when Drew came along, their delicate, thoughtful son, nothing changed. Quiet, easy, he fit so perfectlyâin temperament, in dispositionâwith everything that was already happening. Devon was happening.

After one meet, Devon medaling in three of four events, in the car on the way home, their fingers stiff from cold, Eric asked Devon, age nine, how it was, how it felt.

“I beat everybody,” she said, solemnly. “I was better than everybody.”

Her eyelashes blinking slowly, like she was surprised.

And Katie and Eric had laughed and laughed, even though Katie felt sorry, always did, for all those other girls who just weren't as good, didn't have that magical something that made Devon Devon.

“You gotta get her out of there,” a competition judge confided to Eric the following day. “Ditch that strip-mall gym. Get her to BelStars. Get her to Coach T.

“You keep her here, it'll all go to waste.”

And that very night Eric began researching second mortgages.

It was, Katie had to admit, exciting.

Â

Coach Teddy Belfour watched Devon's tryout, rapt.

“Let me offer you a big, mouth-filling oath,” he told Katie and Eric, never taking his eyes from her. “Bring her to BelStars and she'll find the extent of her power. We'll find it together.”

That was how he talked, how he was.

The next day, Devon was on the BelStars beam, under the tutelage of the exalted Coach T., the most decorated coach in the state, the silver-maned lion, the gymnast whisperer, the salto Svengali, molder and shaper of fourteen national champions at the Junior Olympic and Elite levels.

That night, Eric told Katie how he and Devon had walked past the long rows of beams and bars, the fearsome BelStars girls whippeting around with faces grim as Soviets'.

He thought she would be terrified by the time they finished the gauntlet. But instead she'd looked up at him, her eyes dark and blazing, and said, “I'm ready.”

Â

And overnight BelStars became their whole world.

Twelve thousand square feet, a virtual bunker, it had everything that jolly Tumbleangels, run by two sweet women both named Emily, didn't. The color-coordinated foam wedges and cartwheel mats were replaced by mammoth spring floors, a forty-foot tumbling track, a parent lounge with vending machines. All of it gray, severe, powerful.

And she had Coach T., nearly all his energies devoted to Devon, beneath her on the beam, the bars, spotting her at the vault. Barking orders at everyone but Devon. (“She doesn't need it,” he said. “She just needs our faith.”)

This was the place Devon began spending twenty-five hours a week, before school, after school, weekends. And, because it was thirty minutes from their house and Eric's work schedule was unreliable, it was often the place Katie and thus little Drew spent four, five, seven hours a day, Katie's default office, her laptop open, trying to do her freelance design jobs.

But it was impossible not to watch Devon. Everyone watched her.

Katie and Eric tried never to say the word

Olympics.

But it was hard not to think about. Because it was all anyone at BelStars thought about.

“Once in a generation,” one of the other parents said, watching Devon.

You never think you'll hear a phrase that big in real life, much less find yourself believing it.

You never think your life will be that big.

Â

Just after Devon's tenth birthday, Coach T. pulled Katie aside.

“Let's meet tonight. You and Eric and me,” he whispered so no other parent could hear. “To talk about our girl's future. Because I see things bright and bountiful.”

And so it was, that night, sitting at the grand dining-room table of his grand home, Coach T. pulled out a large easel pad and showed Katie and Eric the flow chart, punctuated by fluorescent arrows, Sharpied hieroglyphics. It was titled “The Track.”

“My friends, this is a decision point,” he said, perpetually bloodshot eyes staring over at them. “Are you ready?”

“We are,” Eric said.

“Yes,” Katie said. “Ready for what?”

Teddy laughed buoyantly, and then they all did. Then, turning the easel paper toward her, he waved his pen, magician-like, and explained.

“Devon's on the brink of becoming a Level Ten gymnast,” he said. “The highest level.”

“And she can top out at Ten,” he said, shrugging a little. “And be proud of herself. Compete in big events across the country. Attract recruiters for a college scholarship.”

He looked at them, that forever-ruddy face, the dampness of his bloodhound eyes.

“Or she can take the other path, the narrow one. The challenging one. The one for the very few indeed. The Elite path.”

E-lite.

It was all anyone talked about in the gym.

Elite-Elite-Elite.

A constant purr under their tongues. The trip of the

l

, the cut of the

t

.

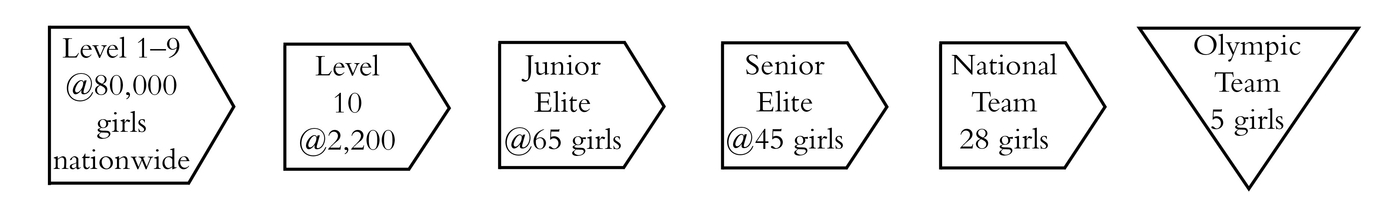

“Going Elite means going from competing nationally to competing internationally,” Teddy said. “If this is the desired track, she needs to qualify as an Elite gymnast. First, Junior Elite, and she's not even close to ready yet. I'm shooting for her thirteenth birthday. Then Senior Elite, the year she turns sixteen.”

All three were silent for a moment. Eric looked at Katie, who looked back at him, trying not to smile.

“An Elite career lasts five or six years, max. But each year, the hundred, hundred and twenty Elites compete to land spots on the national team. From the national team, you are only one step away from⦔

Teddy paused, briefly, watching Katie and Eric, letting the moment sit with them.

Then, with his thickest Sharpie, he underlined the words

Olympic Team

and circled it, and starred it.

The words themselves like magic, an incantation.

Katie felt for Eric's arm and then began to pull back, embarrassed.

But Eric grabbed for her, clutched her hand. And Katie could feel it, an energy vibrating off him, like sometimes when they watched the meets together, their bodies humming beside each other, so alive.