Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (28 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

For decisions to be translated into effective and unconflicted behavior, a person has to be motivated to approach the new thinking and goals after being committed to the new decision. New attitudes will develop, and a person has to be able to align these attitudes with

the new goal in a consistent manner for the new goal to be achieved. As just described, the dissonance associated with the new decision is likely to accompany the new actions necessary for the actual change to occur. Change is uncomfortable. The sections on energy utilization, longer brain processes, and switch-costs provide some explanation as to why this is the case.

Conflict detector activation and cognitive dissonance:

Cognitive dissonance is associated with increased sympathetic nervous activity that is reflected in increased skin conductance.

41

,

42

In the brain, dissonance would be expected to evoke activity in the anterior circulate cortex (ACC), which has been associated with error monitoring and the detection of conflicts in thinking.

43

More importantly, recent research has found increased ACC activity when behavior conflicts with the self-concept.

44

Once dissonance is aroused or conflict is detected by the ACC, the brain can move ahead with its plans to reduce this conflict.

Changing requires activation of the left frontal cortex:

As described earlier, a recent study using brainwave (EEG) recordings showed that a neurofeedback-induced decrease in relative left frontal cortical activation, which has been implicated in approach motivational processes, caused a reduction in spreading of alternatives. That is, a decrease in left frontal cortical activation made switching to the more positive view of a new decision more difficult. A follow-up experiment manipulated an action-oriented mindset following a decision and demonstrated that the action-oriented mindset caused increased activation in the left frontal cortical region as well as increased spreading of alternatives. The results of the present two experiments strongly suggest that the process of dissonance reduction following commitment is due to action-oriented processing, which is evident in relative left frontal cortical activation.

45

Emotional sanctions are needed for action:

Another way in which brain researchers study “action” is to study the primary motor cortex involved in literal movement while relating this center for literal movement to the stimuli and emotions that precede the movement.

Researchers are increasingly finding that the final movement (which correlates with increased primary motor cortex activation) occurs after processing by other brain regions. Specifically, one interesting finding is that emotional experiences are coded by the limbic system and then sent to the supplementary motor area (SMA) prior to reaching the primary motor cortex.

46

This suggests that emotions can become actions if this chain of events is unobstructed. However, if it is obstructed anywhere along the chain, the final action will not occur. Also, as pointed out earlier on, the SMA, being a multimodal structure, is more powerful than the primary motor cortex in terms of susceptibility to change. Thus, any desired change in action should involve factors that affect the SMA rather than the primary motor cortex.

Simply put:

• Making a change requires feeling uncomfortable about where you are.

• Feeling uncomfortable will stimulate thoughts and actions.

• Actions (and not thoughts) are critical in stimulating motivation and goal-directed behavior (thoughts alone will not do it).

• These actions are largely mediated by the left frontal cortical region after detection by the ACC.

• New actions are more likely if we target the association areas of the brain rather than the primary brain region responsible for an action.

The application:

So, from this research, how can managers, leaders, and coaches apply a knowledge of action?

• Knowledge of action relates to task switching and memory as well. Review the costs of action through these lenses.

• Action requires initial cognitive dissonance. Expect this, and educate clients about this requirement, because the ACC (conflict detector) needs to communicate this information to the relevant change centers.

• Thinking about a new course of action does little to increase the frontal activity necessary for change to occur. Actions are much more powerful in enhancing left frontal cortical activity.

• Action is best promoted by stimulating related brain regions rather than the actual action itself. Conceive of emotions/related actions that will stimulate the primary action center. Stimulating the association cortex will stimulate the primary brain region needed for the action to occur.

One of the major obstructions to change is resolution of cognitive dissonance in the opposite direction to the one that someone wants. When we try to move forward, we have to teach clients that this is an uncomfortable process. This process can be addressed by increasing negativity about the past, increasing positivity about the future, and by breaking the future fears into pieces. Spreading of alternatives is not just a cognitive process; it is an emotional one as well. The commitment has to be emotional too.

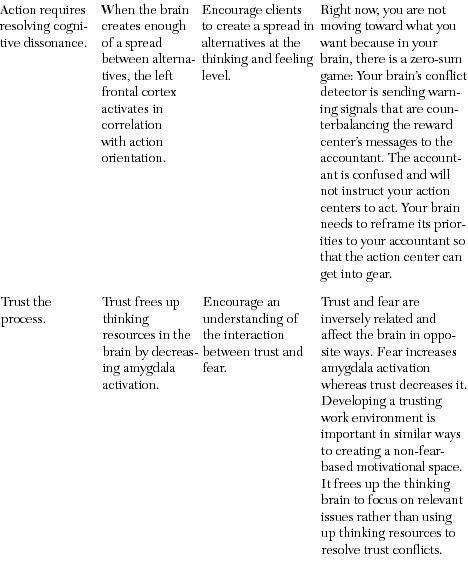

The following language can be used: “Right now, you are not moving toward what you want because in your brain there is a zero-sum game: Your brain’s conflict detector is sending warning signals that are counterbalancing the reward center’s messages to the accountant. The accountant is confused and will not instruct your action centers to act. Your brain needs to reframe its priorities to your accountant so that the action center can get into gear.”

Here are the basic neuroscientific principles concerning actions promoting change:

• If you imagine, imagine actively in terms of the actual task needed to be done rather than an abstract list of what needs to be done.

• Acting will increase motivation for the new task (and increased left frontal activity).

• Expect the old task to create cognitive dissonance (and ACC activation).

• Related actions are sometimes more effective in increasing the chances of a direct action that is difficult to perform. If, for example, you are hired to promote productivity in a worker who works for a “monster” that requires making more telephone

calls to increase sales (or if you are a manager at that firm), engage the person in the emotional rewards of making the calls, and the anxiety that prevents him or her from making the calls in the first place. Ask him to make a call in front of you and then describe the experience to you, making sure at all times that you and the client are aligned in your goals. If the person has no interest in making more calls, help him understand the basis for this behavior nonjudgmentally and help him understand the cognitive dissonance that will occur when he does in fact decide to change his behavior. Help him understand the personal costs of this tension, prior to relating this to the business.

Emotions and the Brain: Relevance to Change

For a long time, emotions have been identified as a “soft skill” that have nothing to do with how an organization or executive functions. Thus far, we have seen that this is not true in the following ways:

• The emotional system of the brain has direct connections to the action systems.

• The emotional system of the brain has to weigh in with the accountant for decision making to be effective.

• The emotional system of the brain impacts attention (stress increases ACC activation, for example).

• The emotional system of the brain impacts memory and learning (stress diminishes memory functions and DLPFC activation).

Action, attention, memory, and decision making are all critical to the functioning of organizations and any human being. Therefore, emotions are influential and need to be understood well when we coaching our clients.

In February 2009, a group of business experts—including John Mackey (CEO of Whole Foods), Marissa Mayer (Vice President of Search Product and User Experience at Google), Lenny Mendonca

(Senior Partner at McKinsey), and Vineet Navar (from HCL Technologies)—got together to innovate around the priorities for reinventing management. Among their 25 recommendations were the following:

47

• Fully embed the ideas of community and citizenship in management systems. There’s a need for processes and practices that reflect the interdependence of all stakeholder groups.

• Reduce fear and increase trust. Mistrust and fear are toxic to innovation and engagement and must be wrung out of tomorrow’s management systems.

• Dramatically reduce the pull of the past. Existing management systems often mindlessly reinforce the status quo. In the future, they must facilitate innovation and change.

• Empower the renegades and disarm the reactionaries. Management systems must give more power to employees whose emotional equity is invested in the future rather than the past.

• Enable communities of passion. To maximize employee engagement, management systems must facilitate the formation of self-defining communities of passion.

• Further unleash human imagination. Much is known about what engenders human creativity. This knowledge must be better applied in the design of management systems.

Emotions may impact change in significant ways, and trust, empathy, and optimism may all facilitate actions. These concepts are found in the following chapters:

• For more on the neuroscience of trust, see

Chapter 3

, “The Neuroscience of Social Intelligence: Guiding Leaders and Managers to Effective Relationships.”

• For more on the neuroscience of empathy and social intelligence, see

Chapter 3

.

• For more on the neuroscience of optimism, see

Chapter 2

, “How Does Positive Thinking Affect the Business Brain?”

The application:

In these chapters, we have outlined an approach to managing emotions using a neuroscientific approach. The coach or manager can say to the leader: “Your emotions are an important input to your brain’s accountant, which eventually tells the action center whether or not to act. Learning how to manage these emotions under difficult situations is critical to getting to action.”

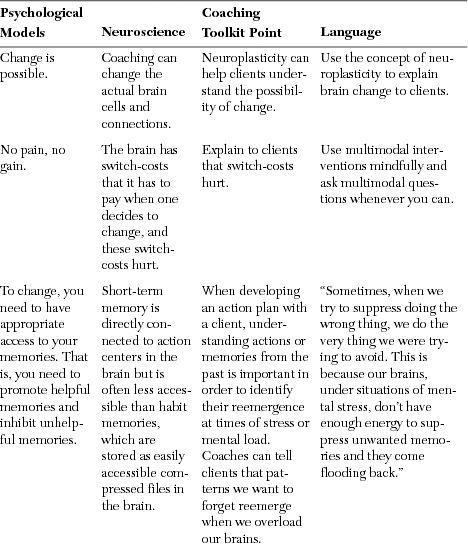

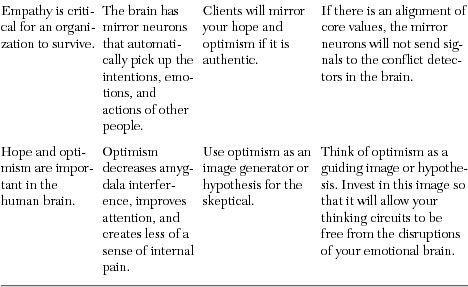

Table 6.1

outlines how we can apply the principles underlying the brain science of moving to action in the business environment.

Table 6.1. Concepts Related to Action