Your Face Tomorrow: Poison, Shadow, and Farewell (59 page)

Read Your Face Tomorrow: Poison, Shadow, and Farewell Online

Authors: Javier Marías,Margaret Jull Costa

No, Tupra would not be prepared to lose us so easily, the people who served him. I didn't consider that I as yet owed him any large debts or loyalties, nor had I established any very strong links, I had not become involved, enmeshed or entangled, I would not have to use a razor to cut one of those bonds when it ultimately grew too tight. I had tried to deceive him regarding Incompara, but now, with this Dearlove business, even if it wasn't quite the same thing, we were more or less quits. It was likely, on the other hand, that he had young Pérez Nuix caught from various angles, and that for her there could be no easy separation, no possibility of desertion. I remembered Reresby's comment when he froze the video image of her beaten father, the poor man lying motionless on the table, a swollen wounded heap, bleeding from his nose and eyebrows, possibly from his cheekbones and from other cuts, the broken hands with which he had tried in vain to protect himself-—I, too, had broken a hand and slashed a cheekbone with apparent coldness or perhaps with genuine coldness, how could I have done that? Tupra had said: 'As I told you, nothing here gets thrown away or given to someone else or destroyed, and that beating is perfectly safe here, it's not to be shown to anyone. Well, who knows, it might be necessary to show it to Pat one day, to convince her of something, perhaps to stay and not to leave us, one never knows.' Perhaps he would show it to her, saying: 'You wouldn't want this to happen to your father again, would you?' 'How fortunate,' I thought, 'that my family is far away and that I'm all alone here in London.' But maybe he wouldn't need to go that far to convince Pat: after all, she may have been half-Spanish, but she was still serving her country. And I was not.

I slept badly that night, having resolved to get up early the next day. I had no intention of spending Sunday in London doing nothing but ruminate, with barely anything to occupy me (I'd dealt with any work pending before I left for Madrid), and with the television watching me while I waited for Monday to arrive so that I could talk to Tupra. I hadn't been to see Wheeler for a long time and, besides, there was the heavy present that I'd bought for him in a second-hand bookshop in Madrid and carted with me all the way to London: a boxed, two-volume set of propaganda posters printed during our Civil War, some of which—not only the Spanish ones and not all of them cartoons—used the same message as the 'careless talk' campaign or something very similar. And when you've taken the trouble to carry something with you, you feel impatient to hand it over, especially if you're sure the recipient of the gift will be pleased. It was a little late to call him on Saturday night when I returned from Baker Street, and so I decided to go to Oxford in the morning and tell him of my arrival there and then; it wouldn't be a problem, he hardly ever went out and would be delighted to have me visit him in his house by the River Cherwell and stay to lunch and spend the whole day in his company.

And so I went to Paddington, a station from which I had so often set off in my distant Oxford days, and caught a train before eight o'clock, not noticing that it was one of the slowest, involving a change and a wait at Didcot. During what was still more or less my youth, I had, altogether, waited many minutes at that semi-derelict station, and I'd been convinced on one such occasion that I'd lost something important because I'd failed— almost—to speak to a woman who was, like me, waiting for the delayed train that would take us to Oxford, and while we passed the time smoking, the hesitant pool of light surrounding us had illuminated only the butts of the cigarettes she threw on the ground alongside mine (those were more tolerant times), her English shoes, like those of an adolescent or an ingénue dancer, low-heeled with a buckle and rounded toes, and her ankles made perfect by the penumbra. Then, when we boarded the delayed train and I could see her face clearly, I knew and know now that during the whole of my youth she was the woman who made the greatest and most immediate impact on me, although I also know that, traditionally, in both literature and real life, such a remark can only be made of women whom young men never actually meet. I had not yet met Luisa then, and my lover at the time was Clare Bayes; I didn't even know my own face and yet nevertheless there I was interpreting that young woman on the platform of Didcot station.

The train stopped at the usual places, Slough and Reading, as well as Maidenhead and Twyford and Tilehurst and Pangbourne, and after more than an hour, I got off there, in Didcot, where I had to wait several minutes—on that so-familiar platform—for another weary and reluctant train to appear. And it was there, while I was vaguely recalling that young nocturnal woman whose face I soon forgot but not her colors (yellow, blue, pink, white, red; and around her neck a pearl necklace), that I understood what had made me get up so early in order to catch a train and visit Wheeler in Oxford without delay; it wasn't simply a desire to see him again nor mere impatience to watch his eyes when they alighted with surprise on those 'careless talk' posters from Spain, it was, secondarily, a need to tell him what had happened and to demand an explanation. I don't mean tell him about what had happened to me in Madrid, for which he wasn't remotely to blame (to be accurate, nothing had happened to me,

I

had done something to someone else), but about what had occurred with Dearlove; after all, Peter was the person who had got me into that group to which he had once belonged, the person who had recommended me; he had made use of my encounter with Tupra and submitted me to a small test that now seemed to me innocent and idiotic—and which in no way prepared me for the possible risks of joining the group—and then reported to them on the result. Perhaps he himself had written the report on me in those old files: 'It's as if he didn't know himself very well. He doesn't think much about himself, although he believes that he does (albeit without great conviction) . . .' He it was, in any case, who had revealed to me my supposed abilities and who had, to use the classic term, enlisted me.

Once in Oxford, I walked from the station to the Randolph Hotel and phoned him from there (now that I knew Luisa used a cell phone, perhaps I ought to get one too, they may be instruments of surveillance but they have their uses). Mrs. Berry answered and didn't even think it necessary to hand me over to Peter. She would ask him, she said, but she was sure my visit would make his day. A few seconds later, she was back: 'He says you should come at once, Jack, as soon as you like. Will you be staying for lunch? I'm sure the Professor won't let you leave before then.'

When I went into the living room, I experienced a moment of alarm—but not quite panic—because Peter's face had taken on the gaunt look of those whom death is pursuing although without as yet too much haste, not yet holding the hourglass in his hand, but keeping a close eye on it. That impression soon diminished, and I decided it must have been a false one, but it may also have been due to a rapid adjustment, as when we meet a friend who is much fatter or thinner or older than the last time we saw him and we are thus obliged to carry out a kind of rectification process, until our retina gets used to our friend's new size or new age and we can again fully recognize him. He was sitting in his armchair, like my father in his, with his feet on an ottoman and the Sunday papers scattered on a low table beside him. His stick was hooked over the back of his chair. He made as if to get up to greet me, but I stopped him. Judging from the way he was settled in his armchair, it seemed to me unlikely that he would find it as easy to sit down on the stairs as he had done very late on the night of his buffet supper. I placed one hand on his shoulder and squeezed it with gentle or restrained affection—that was the most I dared to do, for in England people rarely touch each other. He was impeccably dressed, with tie and lace-up shoes and a cardigan, as was, I believe, customary among men of his generation, at least I had noticed the same tendency in my father, who, when he was at home, always looked as if he were about to go out at any moment. Then, impatient to begin, I sat down on a nearby stool and the first thing I did, after exchanging a few words of welcome and greeting, was to remove from my bag the package containing

La Guerra Civil en dos mil carteles—The Civil War in Two Thousand Posters

—the next time I went to Madrid I would have to track down another copy for myself; it really was a marvelous book, and I was sure that Wheeler would appreciate and enjoy it greatly, as would Mrs. Berry, whom I urged to stay and leaf through it with us. However, she preferred not to ('Thank you, Jack, I'll look at it properly when I have more time'). And she left us on the excuse that she had things to do, although throughout the morning, she came back into the room several times, came and went, always near, always on hand.

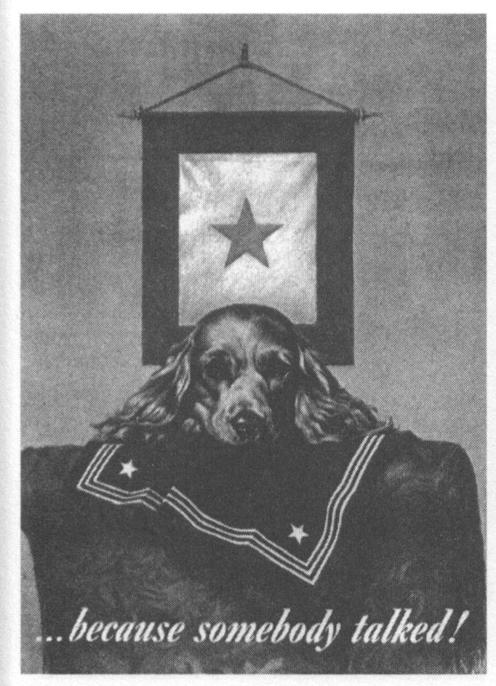

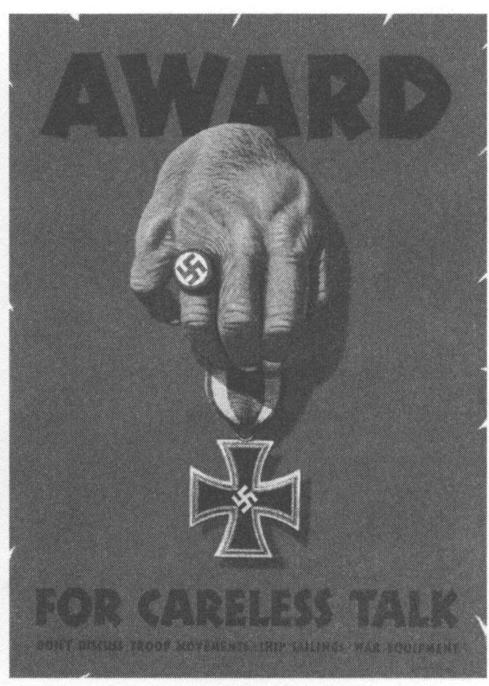

'Look, Peter,' I said, opening the first volume, 'the book also reproduces various foreign posters too, and I've stuck post-its on any pages that have posters connected to the "careless talk" campaign. It seems that, as a recommendation, it was pretty much a constant in all kinds of places. The British campaign was imitated by the Americans when they finally entered the War, but theirs sometimes verged on the kitsch and the melodramatic 'And I showed him a drawing depicting a dog grieving for its dead sailor master '. . .because somebody talked!' or as we would say in Spanish: '

¡ .

. .

porque alguien se fue de la lengua!';

another in which appeared a large hairy hand wearing a Nazi ring and holding a Nazi medal and the words: 'Award for careless talk. Don't discuss troop movements, ship sailings, war equipment'; and a third more somber one, in which a pair of intense narrow eyes peer out from beneath a German helmet: 'He's watching you.' And there are two English posters that I

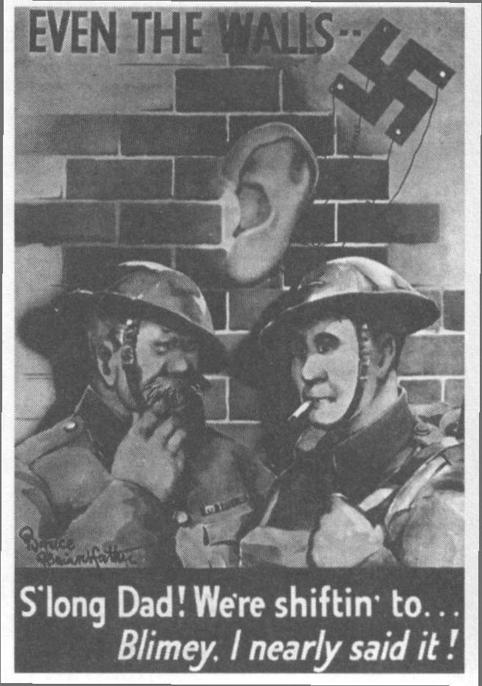

don't think you showed me, but that you're bound to remember.' And I turned to a page displaying a very succinct poster bearing only the words 'Talk kills,' the lower half of which showed a sailor drowning as an indirect or possibly direct result of someone talking; and another signed by Bruce Bairnsfather, which revived his famous soldier from the First World War, 'Old Bill,' alongside his son who has been called up for the Second.

At the top are the words: 'Even the walls . . .' next to a swastika and above a huge ear; and underneath are written the young man's words: 'S'long Dad! We're shiftin' to . . .

Blimey. I nearly said it!'

And I pointed out to him a French poster, signed by

Paul Colin: 'Silence. The enemy is listening in to your secrets' and a Finnish one, although the words were in Swedish, that showed a woman's full red lips sealed shut by an enormous padlock, and the text of which apparently said: 'Support our soldiers from the rearguard. Don't spread rumors!'; and a Russian poster in which one half of the listener's face and shoulders was much darker and had acquired a monocle, a mustache and a military epaulette (had taken on, in short, a very sinister appearance). And here are the Spanish posters,' I added, leafing through the second volume where most of them were to be found, although they were scattered throughout both. 'You see, these must have predated the British ones and the others too.'