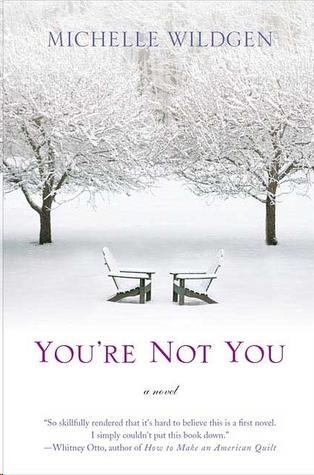

You're Not You

Y

OU’RE

N

OT

Y

OU

OU’RE

N

OT

Y

OU

Michelle Wildgen

T

HOMAS

D

UNNE

B

OOKS

S

T

. M

ARTIN’S

P

RESS N

N

EW

Y

ORK

THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS.

An imprint of St. Martin’s Press.

YOU’RE NOT YOU.

Copyright © 2006 by Michelle Wildgen. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wildgen, Michelle.

You’re not you: a novel / Michelle Wildgen.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-312-35229-8

EAN 978-0-312-35229-5

1. Women college students—Fiction. 2. Caregivers—Fiction. 3. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—Patients—Fiction.

PS3623.I542 Y68 2006

813’.6—dc22

2006040200

First Edition: June 2006

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my family

I’M VERY GRATEFUL TO

Prairie Schooner

for publishing the short story “You’re Not You” and to the Hall Farm Center for Arts and Education for providing a beautiful and welcoming work space to expand the story into a novel.

Bay Anapol, Jenn Epstein, Krista Landers, Steve O’Brien, Jon Raymond, and Claudia Zuluaga were insightful and encouraging readers who rarely resorted to outright mockery. Emily Dickmann, Tom Kuplic, Melissa Irr, Alison Weatherby, and the Wildgen and Rootes families all listened graciously to each report on the whole project, which I shared in excruciating detail.

Emilie Stewart’s energy and enthusiasm are boundless. I’m extremely grateful for everything she did for this book, which was a lot. A big thank-you to Anne Merrow at Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press for her guidance and zeal, perceptive edits to the book, and zipping back to the office on a Friday evening to find out how it ends.

Thanks to the staff of

Tin House

magazine for the practical advice, indulging my bitter streak, and getting me out of the house a few times a week.

I feel immense compassion for all who miss out on being an aunt to the following incomparable small people: Justin! Taylor! Christopher! Caroline!

Last and most important, thanks to those who have provided the most gracious hospitality both at home and abroad, the wittiest commentary on the stupidest movies, and the loveliest solstice dinners. You know who you are.

Y

OU’RE

N

OT

Y

OU

I

WOULD BEGIN ON

Thursday morning. The idea was for me to arrive early, by seven thirty, so Evan could show me what he did for his wife before he left for work, and afterward I’d follow him and Kate through a typical morning and afternoon. I had one day to observe and then training was over.

I began the morning by smacking the snooze button in a single well-aimed flail at six fifteen. I then lay immobile, arm outstretched and palm still flat against the warm grooves of the clock, enumerating my regrets over the switch from a night job to a morning one, until the alarm resumed.

After a pot of coffee, however, I began to change my mind. It turned out our living room windows faced east and sunlight flooded the room, something I had not had the opportunity to note in the nine months I had lived here. I settled myself before the television, coffee cup a pleasingly warm weight on my stomach, careful not to unbalance the couch (a green and gold yard-sale affair we had to treat gingerly, since Jill and I had hacked off one of the legs to get it in the front door, then propped it back on the splintered stump). I even opened a window to let in the breeze. You really could hear birds chirping in the morning—that wasn’t just in folk songs. I sipped my coffee and listened to the anchors’ chitchat. Things were happening in the world. For once I knew what some of them were.

By the time I arrived at the Norrises’ house, I felt downright hale. My lungs, I thought, breathing deeply as I rang the bell, seemed to be of genuinely admirable capacity.

Evan opened the front door. “Bec,” he said, smiling. “I guess this is the official welcome. Come on back to the bedroom.” He was wearing dark pants, a neatly ironed white shirt.

I watched his hands swing as we walked to the back of the house, liking him. Something in Evan’s gait seemed familiar, but then lately I had detected a bizarre habit of trying to associate every person I liked with Liam: If Jill made me laugh I listened to the tone of her voice to see if it was like Liam’s when he told a story; if a guy on the street gave me a certain kind of smile I searched his face for Liam’s thick eyebrows or his straight white teeth.

In the bedroom Kate was in her wheelchair, already dressed in a khaki skirt and blue T-shirt. Her damp hair left dark patches on the shoulders of her top. Her face was pale and bare, her eyes soft. Without makeup she seemed soft-fleshed, vulnerable as an open mollusk. When she spoke to me, her voice was low, the words slurred and indistinct though it was clear she was trying to enunciate. Evan translated after each phrase, switching pronouns and glancing back and forth between us.

“So we let Evan . . . do everything today . . . and you watch, okay? Sometime I’ll have you dress me . . . just so you know how, but . . . we can do that later.”

When this last part was repeated, Kate gave me a sheepish smile. I said, “Oh, don’t worry. I’ll learn soon enough, right?” Maybe at the beginning she always gave herself a little grace period before she showed a total stranger everything. Frankly, I was grateful for the wait. I might not stay at this job beyond the summer. Perhaps I would never have to deal with dressing, period.

But I was resolved to put in the three months till September. Look at Jill—back in high school she’d stuck it out, for no money, volunteering at an ugly nursing home for almost a year. By contrast, I’d found a pretty easy deal (I allowed myself a moment of superiority), and presumably I had a bit more fortitude at twenty-one than Jill had had at seventeen.

“So,” said Evan, clasping his hands, “let’s get to it.”

The three of us went into the bathroom, which was palatial. There was room for three chairs, Kate and Evan facing each other next to the

counter and me standing perpendicular to them, opposite the mirror. On the counter was a neatly divided compartment case of makeup and a few pricey hair products lined up near the sink: bottles of creams and mousse and a vial of something syrupy and clear.

Evan held up a bottle and said, “First you take a little of this and rub it on your hands and put it through her hair.”

She let her head tip back as he combed his fingers through her hair, which looked silky and heavy, and rubbed his palms over the crown of her skull. The cream smelled of limes and coconut. That was just fine. I knew how to do that. He combed her hair back from her face, parting it to one side. I made a mental note that it was the left side. Her skin was pale, flushed through the cheeks and dusted with freckles I hadn’t noticed the day before. Her eyes, a light, clear tortoiseshell amber, bore a burst of gold around the pupils. It was not a girlish face, but built of firm lines instead, her eyebrows slanted rather than blandly curving, her nose long and straight, the tip slightly angled toward her lips, her mouth wide but not especially full. It was the face maybe not of a model but of a tall woman, its scale too bold to be comfortable on a petite frame. How tall had she been? Five eight, five nine? Not just the chair but her thinness made it difficult to guess. The proportions were off.

When he finished she said through Evan, “How are you with makeup?”

My hand darted up to my face. Then I knew I should have put on a little, out of deference to the job. I hated makeup—my eyelashes felt stiff when I wore mascara, and I always forgot powder. I never understood how Jill could go out on a hot summer morning with her eyes smoky and dark and her mouth covered in a coat of burgundy lipstick. Yesterday at the interview Kate hadn’t seemed to be wearing much, but now I guessed it was the kind of expertly blended makeup that only looks like nothing.

“I can learn,” I hedged.

“Evan learned,” Kate said.

“Oh, then no problem,” I said. I took out some mints and offered the tin around. It was as though we were just girls hanging out. Except for the husband it felt like junior high. Of course, if I had paid better attention in junior high makeup sessions I might have known what I

was doing by now. “This is going to be good for me,” I said, through a mouthful of mints. “My roommate’s been bugging me to wear some mascara since we were thirteen.”

Kate smiled as she lifted her face to Evan. He dotted her skin with foundation and smoothed the makeup out, covering the freckles across the bridge of her nose, which I thought was too bad. Then he dusted her cheeks with blush and held up two compacts of eye shadow. She looked them over for a moment and then nodded at one, saying in that low voice something that sounded like “just a little.” Evan went to work like a pro, whisking taupe shadow over her closed eyelids and feathering a stiff brush, tipped with brown powder, against the grain of her eyebrows and then brushing them back into place.

It was a brisk, impressive procedure, and as I watched I wondered if I would ever go through anything like it myself if I were her. She didn’t have to go out every day, yet she did her hair and put on a full face of makeup? It seemed silly, so precious, to go through all these motions for nothing. But perhaps she simply liked to feel polished.

Evan lifted her face with a knuckle beneath her chin and caught her eyelashes in a curler. “If I ever get sick of the marketing game I’m going to go pro as a makeup artist,” he said, then wiped extra mascara off a wand and started brushing it up and down Kate’s lashes.

“I’d pay you,” I said. He laughed and held up a couple of lipsticks. Kate nodded at one in his right hand. As he finished with her lips, the two of us looked her over. It was the same face I’d seen yesterday, her but intensified, her eyes darkened slightly and her mouth rosy. Now that I’d seen him do it, makeup didn’t seem so mysterious.

Evan leaned down and used the tip of his thumb to brush away a bit of powder, his face intent. He smiled at her. Maybe the makeup was for him.

Finished, they turned to look at me. I glimpsed us all in the mirror, the backs of their tawny heads gleaming in the reflection as they faced me, and between them the pale oval of my face. After looking at Kate, whose coloring was faintly golden, my own skin seemed whiter, my nose a formless little button and my cheeks more rounded than I’d ever noticed, my naked eyes a wolfish gray.

“Think you can do this tomorrow?” she said.

“Sure,” I told her. I considered practicing on Jill tonight but decided I wouldn’t need to. Tomorrow I would just remember that all I had to do was enhance what was there and I’d be fine.

THEIR AD HAD CAUGHT

my eye because it was so calm, free of suspicious overenthusiasm and exclamation points. Very few jobs deserved that kind of punctuation, and I appreciated an employer who recognized that. They were seeking a helper for the wife, who had Lou Gehrig’s disease. When I phoned, I was imagining reading books to her, serving tea that smelled of something crisp and bracing, like mint. Even after Evan said Kate was only thirty-six, I persisted in imagining someone tremulous and elderly, someone you take one look at and know she needs your help—your humor, your height, your muscled arms.

I may have been inventing everything else, but I knew the most important thing: The salary was fifteen dollars an hour, assuming I turned out to be a caregiving sort of person and got the job. I had no idea if I was this sort of person or not—it’s my belief that sometimes you just let the experts decide. They weren’t even looking for a nurse, or a true home health care worker. Helping out, Evan said on the phone. Driving her around, making phone calls, lending a hand around the house. How hard could it be?