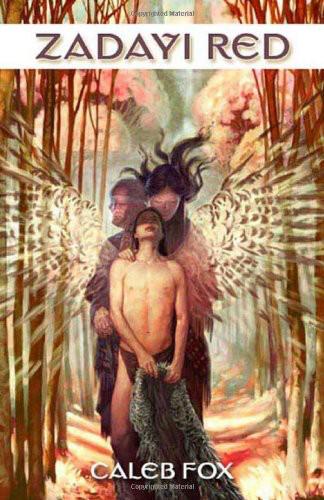

Zadayi Red

Authors: Caleb Fox

Z

ADAYI

R

ED

Z

ADAYI

R

ED

Caleb Fox

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

ZADAYI RED

Copyright © 2009 by Winifred Blevins and Meredith Blevins

All rights reserved.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

[http://www.tor-forge.com] www.tor-forge.com

Tor® is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fox, Caleb.

Zadayi Red / Caleb Fox.—1st ed.

p. cm.

“A Tom Doherty Associates book.”

ISBN-13: 978-0-7653-1992-0

ISBN-10: 0-7653-1992-6

1. Cherokee mythology—Fiction. 2. Gods—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3606.O89Z24 2009

813'.6—dc22

First Edition: July 2009

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

M, let’s dance!

M, let’s dance!

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you, wife, for being my partner, my muse, and my gang foreman.

Thanks to my mentors, John G. Neihardt, Clyde Hall, Dale Wasserman, and Larsen Medicine House.

The first distinction we need to make here is between prehistoric and historic. . . . “Prehistoric” has to the average ear a misleading ring of the primitive, the savage, even the prehuman, whereas all it really means is preliterate. Life without pencils is still life, and stories need not be written down to be remembered.

NE

S

unoya, isn’t it time?”

She couldn’t tell him. Couldn’t tell him about the dream, couldn’t tell him what was basically wrong.

Sunoya looked into the warm, acorn-colored eyes of her Uncle Kanu. The two of them sat across the center fire of the home they shared with the rest of their family. She knew he loved her. She loved him. But he didn’t understand. She’d been hiding the dream from him, uncertain of its meaning—terrified of its meaning. And she’d been dishonest with him. No doubt about that, and no choice.

Now he thought it was time to honor her, to lift her up to replace himself as the village’s Medicine Chief.

Impossible.

She puffed breath out. She had to say something. “Uncle . . .?

“Sunoya?”

For weeks she’d been seeing something. It came to her at night, when she was sleeping. It came to her in the mornings, when she woke up early and lay in her elk blankets, looking at the small disc of sky through the smoke hole in the hut. It came to her in the afternoon, when she bent down to the river to fill her gourd with water for the family. She couldn’t stop seeing it. Dream, vision, it didn’t matter what she called

it. She’d seen the Cape of Eagle Feathers bloodied, corrupted, fouled, stinking. It haunted her.

She had to do something. Except that she was flawed.

Might

be flawed.

For now all the tribe praised her. They pointed to the webbed fourth and fifth fingers of her left hand, an omen that came among women of her family every few generations and always marked a shaman. She had gone to the Emerald Cavern and been initiated in the tradition of the most powerful tribal shamans. Kanu said she had prodigious gifts, and told everyone that even at such a young age—she was barely beyond twenty winters—she should be Medicine Chief. The entire village was ready to honor her with position and power.

“Sunoya, is something wrong?”

Suddenly the hut felt oppressive. The faint light from the smoke hole at the top. The strong smells of burned wood and tobacco, the scents of the herbs hung over the door to keep out disease, odors of a dozen human beings living in close quarters. “Let’s go for a walk.”

At least she had gotten some words out.

She gave the old man a helping hand up and led him, ducking, through the door flap.

She looked around at this village of the Galayi people as they strolled. Though their name meant People of the Caves, they now lived in dome-shaped, wattle and daub huts circled around a village green. On the east side of the circle stood an opening, and the two largest huts in the village faced each other across the space. On the north side mounded the hut of the White Chief, whose door was outlined in a geometric design painted in white, symbolizing peace. On the other side was the hut of the Red Chief, with a door outlined in a red design, symbolizing war. The Medicine Chief, Kanu, and his family lived in an ordinary hut in the circle of ordinary villagers.

Medicine power, in the common view, didn’t rank with politics or war.

Smoke wafted out of the holes in the tops of all of the huts. Inside some women were cooking evening meals, and the fires warmed the huts against the night. Outside other women were grinding corn from the harvest. Still others were making moccasins for their men for the coming fall hunt, which would supply meat for the winter. Men were flaking points for the spears, or lashing points to shafts with buffalo sinew. A few skilled men were making darts for their

atlatls,

long rods that acted as levers to hurl spears with great speed.

Several families lived in each hut, grandparents, two or three daughters with their husbands, and a pack of children. She watched some boys throwing balls for their dogs in the middle of the green.

These were her people, and this was their life, ordinary human lives painted in red and blue, the tribal colors representing success and failure. The men wore palm-sized discs of rawhide inside their shirts indicating the state of their endeavors, red paint for victory on one side, blue on the other side for loss. These emblems were called

zadayis

. When a war party defeated the enemy, it came back wearing the red sides outward. If it lost, the men wore the blue sides showing. The same held for hunting parties. All the tribe’s life was written in red and blue.

Any Medicine Chief’s duty was to help these people lead red lives. Sunoya especially was bound by that calling. She knew that she could justify her existence only by taking care of the people. Otherwise, by the augury of her birth, she should have been killed at first breath.

Her people were good at making physical lives—corn crops along the river, berries, acorns, chestnuts, and seeds, meat from the deer, elk, and sometimes buffalo. Clothes cut from tanned deer skins, blankets of elk robes with the hair left on, and every

sort of implement that could be made from wood, stone, and the bones, hoofs, horns, and even stomachs of animals. In practical matters the tribe was strong. Their weakness was that they did not realize, not fully, that these blessings were gifts of the Immortals, earned by walking the red path of goodness and not the blue path of ignorance.

Did she have the courage to act? Did she have the right to act? She was lost, and no one knew it.

She had to tell her uncle. She turned to face him. “First I want to go to the Emerald Cavern again.”

There, it was said.

Kanu waited. It was the way of the Galayi people to be patient, let others speak their minds fully, and only then reply or ask a question. They had met other peoples who talked in a criss-cross way, comments and challenges flying like dogs barked, and they thought this behavior very rude.

Sunoya couldn’t tell Kanu her vision of the Cape. If it was real, it was given as a responsibility to her, not to him.

“I know you think I’m stalling. I know you want me to be elected and given your duties.”

She also knew why. Since his wife died, he felt older than his sixty winters. He was afraid he couldn’t keep up with what the people asked of him. A few wanted spiritual counsel, or healing of illnesses of the spirit. Parents wanted a name for a newborn child. Barren women wanted charms that would give them babies. Would-be lovers wanted songs to mesmerize the girls they pined for. Elderly people, as they approached the time of crossing to the Darkening Lands, wanted interpretations of their dreams. And much more.

“You are right,” she admitted. “I came here to do what you’re asking.” She fingered the webbed fourth and fifth fingers of her left hand. Her mind drifted back over the seven winters she’d been here, ever since her mother died. She’d been sent to this village precisely to learn from Kanu. She

thought with pleasure of her own growing mastery, and his delight in her flair for learning. He had no doubt she was a true shaman.

She looked into her uncle’s eyes and felt awful for not being able to tell him everything he wanted to hear. So simple to say, ‘I accept this responsibility now. It is my path in life.’ But if she was a true shaman, and her birth had not corrupted her spiritual eyes, then what she had seen was true. That meant she was obligated first to do something about her dream.