Zahrah the Windseeker (8 page)

Read Zahrah the Windseeker Online

Authors: Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu

It hadn't crossed my mind till then. I was so flustered by the Dark Market that I hadn't realized it. Nsibidi was not from the north. Aside from the lack of mirrors, she shaved her head close, probably to keep the dadalocks and vines from re-forming, and wore three large gold hoops in each ear. She wore no assortment of beads like southwesterners. She wasn't fat like the northwesterners. She wore no bracelets made from vines like a northeastern women. And she didn't smell of molten metal as the southwestern women did.

Where

is

he from then?

I wondered.

I looked at the ground and then stepped back.

Maybe I shouldn't talk to her after all,

I thought. My instincts were telling me that I should, but, as I said before, I wasn't one to really trust my instincts. I wrung my hands and nervously grabbed one of my locks, my eyes trying to look anywhere but at Nsibidi's shaved head.

"Zahrah, just

ask,

" Dari said, turning from the idiok for a moment. "We're in the Dark Market. Nothing you say here is shocking."

Good point,

I thought.

"OK," I said. "You ... you're dada ... well, have you ever had anything ... strange happen to you?"

She frowned.

"Like what?" Nsibidi asked.

I shrugged, looking at the ground. I glanced at Dari. He was looking back and forth between something one of the idiok had written for him and the idiok next to him, who was wildly gesturing what it meant. Obax was still scribbling something else on his pad of paper.

"Why did you cut your dada hair?" I asked.

"Why don't you cut yours?" Nsibidi replied.

"No!" I said. "I would never ... you didn't answer my question."

"You haven't asked your real question," she said. "I can tell."

"But Iâ"

"I cut it because it grew too heavy to bear," Nsibidi finally said, her voice lowering. "The funny thing was that, for me, it wasn't really about being dada. The hair was just a symptom."

"S-s-symptom of what?" I asked.

Nsibidi looked away.

"What is your question, Zahrah? What is it you came back here to find out?" Nsibidi suddenly snapped, looking me right in the eye. Normally, I'd have clammed up in that moment.

The caged parrots all stopped chattering, looking at Nsibidi. And the man selling them spoke more loudly to keep the attention of an interested customer. He'd found someone willing to buy a multicolored parrot, and he didn't want to lose his chance to be rid of the belligerent bird.

I unconsciously stood up straighter at the sound of Nsibidi's commanding voice. Suddenly Nsibidi looked ten feet tall, tall as a tree.

"I ... I ... oh." I glanced at Dari, who nodded for me to continue. I took a deep breath, and then my words came like water through a bursting dam. "I think I can fly or something, I can float, it happened when I got my menses, I was near the ceiling, oh I am

terrified

of heights. Am I a Windseeker? I think I am. Do you know the word? We read about it in the library. What do I do? What do I

do?

"

I stood there, tears in my eyes, terribly embarrassed at my babbling. My hands were shaking and my heart was pounding hard. I wanted answers so badly, but I was so nervous.

"Practice. Nothing good comes easy," Nsibidi whispered, her eyes wide with shock. Then she nodded, looked up at the tarp, and smiled. "Learn to love the place up there. The rest will come when you want it to. " She paused, her dark eyes burrowing into mine. "You understand?"

I just stared at her. It was all too much information to process so fast.

"You

understand,

" Nsibidi said more loudly and sternly.

I blinked and then nodded slowly. Nsibidi and I stared at each other for several moments. It was the strangest feeling. She knew what I was talking about. She must have lived it all, and she had answers. I felt stunned, speechless. All I could do was just stand there. I wanted to remember her face clearly for when I was home thinking about all she said.

"Can your parents fly, too?" Nsibidi finally asked.

"No," I said. "Just me."

"Both my mother and father are Windseekers, as I and my brother. I've

never

met any others. And you have no idea just how much I have traveled. It's funny. You're afraid of heights," Nsibidi said with a laugh. "How ironic."

She paused for a moment.

"I first cut my hair when I was sixteen because I didn't understand what it was to be a Windseeker," Nsibidi said. "Didn't change what I was, thank goodness. It was just hair and vines. Zahrah, there are things about being a Windseeker that are tough to handle, but that's for when you're a little older. For now, just know that you shouldn't bother resisting the urges you'll have. Now that you know what you are, be ready for things to start."

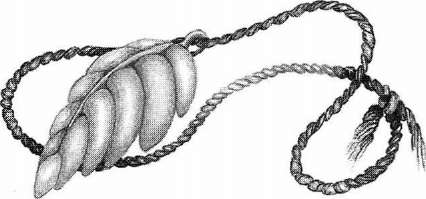

Obax tapped Nsibidi on the shoulder and handed her a piece of paper on which he'd written many symbols. Then the baboon pointed at the necklaces around her arm. Nsibidi read the paper.

She frowned. Then she plucked one of the necklaces from her arm. It had a green leaf pendant. She looked from me to Dari and back to me. She then reread the paper.

"Great Joukoujou," she whispered, placing her hand on her forehead.

"What?" I asked.

She only shook her head.

"It's best that you don't know," she said. "You two ... hmm ... Obax wants you to have this charm, Dari. You'll need it."

I wanted to ask why again but decided against it. I didn't think she'd answer me anyway.

"Um, OK," Dari said with an uncertain smile. He looked at the charm as it twinkled in the dim light. It was very pretty. "Thankyou very much!"

"You're welcome."

I felt a shiver in that moment as I watched Dari put the necklace on.

Why would Dari need a luck charm?

I wondered. That piece of paper Obax had given her ... Obax must have "read" Dari. Oh the questions I had in that moment but was too shy to ask. If only I had been more assertive. And if only we'd had a little longer to talk.

"Zahrah," Nsibidi suddenly said. She paused and looked at the idiok with frantic eyes. I could have sworn many of them were frowning as they waved their hands in the air. She turned back to me with a pained look and said, "Listen to me ... I can't

not

tell you this. I just can't. It would be ... irresponsible. You're going toâ"

"

Dari!!!

"

Dari and I both yelped. It was the voice of Dari's mother. What a horrible moment. Dari and I quickly turned around, shocked at hearing Dari's mother's voice there. Dari jumped up. We could both see his mother's head peeking behind the milling crowd.

"We've gotta go," Dari said quickly.

"Come back when you can," Nsibidi quickly said, taking my hand. "In the meantime,

practice.

Please be careful. Both of you."

It was a strange thing to say. Be careful of what? And what had she been about to tell me? But we had more urgent things to deal with. We held our breaths as we moved toward Dan's mother. It would have been wrong to try to run away. Dari's mother obviously knew we were somewhere in the Dark Market.

When we got close enough, she smacked Dari upside the head.

"For over a

year

Mrs. Ogbu's been telling me she's seen you coming here," she shouted at Dari. I cringed. Mrs. Ogbu sold Ginen fowl sometimes, so at some point she must have been stationed near the Dark Market.

"I didn't believe her! I called her a liar!" his mother continued. "But for some reason, when she told me today she'd seen you, I decided to see for myself. And here you are! I should have taken her more seriously! And you've brought Zahrah, this time?! What in Joukoujou's name are you two doing here!?"

"We were just ... looking around," Dari said, rubbing the side of his head.

His mother was so angry that she didn't say another word. Instead she turned around and began walking. Dari and I quietly followed. She drove me home, and the short trip was silent and very tense. To make things worse, both my parents were home. I knew Dari's mother would go inside with me and tell them. As I got out of the car, I didn't dare speak to or even look at Dari.

"

Chey!

Zahrah, how could you be so stupid?!" my mother shouted the minute Dari's mother was gone. She sucked her teeth with annoyance and put her arms around her chest and just stared at me with amazement. "You and Dari are so bright, I wouldn't expect this of you two."

"I'm sorâ"

"What do you have to say for yourself?" my father said.

"I justâ"

"Forget it," he interrupted. "You don't have the privilege of defense tonight. Just sit there and be ashamed. Be glad you came out of there without some sort of strange disease. It's not a place for people who don't know what they're doing."

"Remember what happened to the Ekois' son?" my mother said, looking at my father.

"Of course," my father replied. He turned to me and looked me right in the eye. "He wasn't seen for fifteen days! They found him chained to seven other children at the Ile-Ife Underground Market! That's a two-hour drive away! Some sick evil man was selling them as child slaves. This man had met the Ekois' son in the Dark Market and promised him free personal pepper seeds if he drank a special drink, a drink that put him to sleep. He woke up in chains. You can guess the rest."

I frowned. Did such bad people lurk in the Dark Market? I knew the answer. Who could forget those miserable-looktng women standing on the platforms or the many types of poisons for sale or those men exchanging all that money? But even with this knowledge, I hadn't

really

thought that I was in any danger. I would never accept anything from a stranger. Did my parents think I was that stupid?

"I'm sorry," I said, my chin to my chest. And I was. I hated worrying, disappointing, or angering my parents.

"You should be," my mother said, lowering her voice. "Now go take a bath and sit in your room and do some thinking."

That night, Dari and I weren't allowed to talk to each other on our computers; nor was I allowed to use my computer for anything but schoolwork. Nonetheless, when I closed my bedroom door, my mind immediately went back to Nsibidi. She was a Windseeker, too. She could fly and she'd traveled far.

I flopped onto my bed and breathed a giggle. I'd never felt so energized in my life.

"Practice," she'd said. I could do that. But where?

Welcome to the Jungle

"I must be crazy to let you talk me into this, " I said as we walked down the road. I nervously glanced behind us. "Crazy!"

"Oh relax," Dari said. "I know what I'm doing."

But I knew Dari. I could hear a little fear in his voice.

"No you don't," I whined. "Someone will

see

us ... or something! What am I

doing

! Oh this is so crazy!"

Only a few days ago, we'd gotten caught in the Dark Market, and what we were doing now was far more forbidden.

"Some risks are worth taking," Dari said.

We'd had to lie this time, telling our parents that we were going to the library. As punishment, we couldn't go anywhere except the library. But we were really going into the Forbidden Greeny Jungle, and we had only a half mile to go as we passed the last building. There was no wall between the outskirts of Kirki and the jungle. For decades, the people of Kirki had tried to build one. The forbidden jungle simply wouldn't allow it.

"This stuff isn't in our school history books. It's really interesting," Dari said as we walked, always a wealth of historical information. "Our government, a long time ago, announced this grand project to build a nine-foot-tall cement wall to shield Kirki from the jungle. But the roots of nearby trees grew under it, and eventually the whole thing just fell apart!"

I shivered as Dan told me about the failed project he'd read about on the net.

He said that when they rebuilt the wall, this time using wood, voracious termites gnawed at it until it fell down. When they rebuilt the wall using metal, insects that had no scientific name dissolved it with acid produced in their thoraxes! These insects glowed a bright orange during the night, and for days, the wall kept nearby residents awake with its light. Eventually the metal wall melted. The wall looked as if it were on fire. It was Papa Grip who put a stop to all the wall-building efforts.

"It's not the Ooni way to do battle with nature," he said that year during his annual address to the town. "If the jungle doesn't want us to put up a wall, then we must

listen

to it, for it's our neighbor and one must respect his or her neighbor."

And so there was no protective wall. The buildings just ended, the grass began to grow higher, then the trees started. A road led to the cocoa bean, palm kernel, and lychee fruit farms located in the jungle's outskirts. The cocoa bean was used mostly for making chocolate. The palm kernels, red clusters of fat seeds chopped from the tops of palm trees, were pressed for oil and then used for cooking and in body lotions and moisturizers. The road went a mile or so into the jungle, and then it quickly tapered off into a very narrow path.