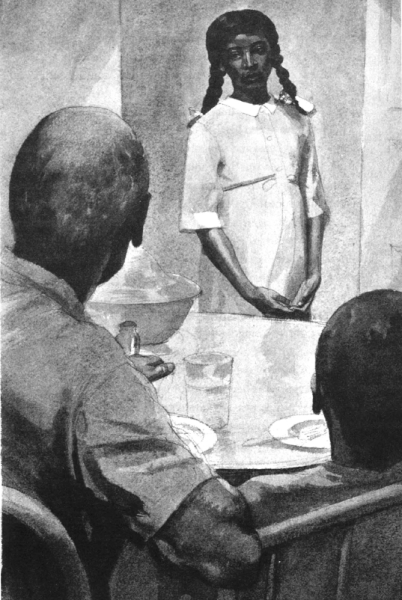

Zeely (11 page)

Authors: Virginia Hamilton

“What

had

you expected?” Uncle Ross asked.

“I wanted her to say right away that she was a queen,” Geeder said.

“Didn’t she look like a queen up close?” Toeboy asked.

“I’d better tell you,” Geeder said. She pushed her plate away. “If I don’t tell you as fast as I can, I won’t believe it ever happened.”

Geeder told Toeboy and Uncle Ross just the way Zeely had been and she didn’t change anything at all. She told them about the robe Zeely had worn and every detail of their meeting. She described the clearing for Toeboy, saying how frightened she had been, seated so close to Zeely. At last she told them about Canada and about the little old woman. She told them the long story of the three couriers. When she had finished, Uncle Ross sighed and smiled.

“When you stayed away so long,” Toeboy said, “I thought for sure you must have found out Zeely Tayber was a queen.” He leaned on his hand, staring thoughtfully into space.

Geeder looked at Toeboy and then at Uncle Ross. She smoothed her hands over her dress and patted her dark curls.

“It’s true,” she said, simply. “There’s not another thing in the world Zeely Tayber could be but a queen.”

Both Toeboy and Uncle Ross were taken by surprise. Before either one could say anything, Geeder was talking.

“Listen!” she said, almost whispering, so that Uncle Ross and Toeboy had to lean forward to hear. Her hands rose before her. She began to divide and shape the air, as though she were making images out of nothing.

“I don’t mean queen like you read in books or hear on the radio, with kingdoms and servants and diamonds and gold! I mean queen when you think how Miss Zeely

is

. Listen! All these hogs going down the road and into town, smelling up the town and squealing. Nat Tayber all covered with mud, just cruel and mean, worse than any animal—I don’t care if he is Zeely’s father. But did anyone ever think of Miss Zeely as smelling like those hogs or being anything other than kind? And listen! All those animals being dirty—no, filthy! Covered with flies and hog wallow, with a stench you couldn’t get rid of in a hundred years. But would you think Miss Zeely was anything but a lady? I mean, working with hogs, having to feed them and walk through them and handle the babies! And having to stay close to old Nat all the time because he is her father and because he gets mean with the hogs sometimes. She doesn’t even know that folks talk about her behind her back. She wouldn’t ever think folks could be as silly as to think she had bewitched those animals. She does her work and I bet she does it better than anybody could.

“Because,” Geeder said, and then she paused a moment, “it’s not what a person stoops to do—oh, no, it’s not! It’s what’s inside you when you dare swim in a dark lake with nobody to help if something should happen. Or, when you walk down a dark road way late at night, night after night.

“Oh, she’s a queen,” Geeder said, “Miss Zeely is the best kind you’d ever want to see!”

There was a silence at the table. They could hear the sound of crickets through the window screen. Uncle Ross looked out the window, surprised to find that night had fallen. He picked up his knife and fork. He had placed them beside his plate when Geeder had first begun to talk about Zeely Tayber.

They finished eating. There was not much talking. After supper, Toeboy and Uncle Ross went into the living room. Geeder went up to her own room. There, she pulled one of the cherry-wood chairs up close to the window. She sat down, gazing out into the night and the west field and stars beyond.

“So much to see here,” she whispered. “Just a few days and nights left before we go back home. Where’s the summer melted to? I don’t recall it going.

“That’s because of Miss Zeely,” she said. “She was the days and nights put together.”

Geeder stared at the stars. They resemble people, she thought. Some stars were no more than bright arcs in the sky as they burned out. But other stars lived on and on. There was a blue star in the sky south of Hesperus, the evening star. She thought of naming it Miss Zeely Tayber. There it would be in Uncle Ross’ sky forever.

“Will I come here again?” she whispered. “Will I come back to see her? No. What’s to see? If I do come again, it’ll be to remember the nights at the same time I’m living them. If she’s here, I will see her. But it will be all right if she’s gone off to some other place. There will be that star.”

Geeder was an hour or more at the window before at last she moved away. She turned on the light and placed the chair where it belonged. She walked around the room collecting all her necklaces from the backs of the two chairs, from the bedposts and from the dresser-drawer knobs. When she had them all, she placed them in the box at the bottom of her suitcase. There they shone in bright flashes.

She looked up, startled. Her hands were still in the suitcase touching the bright necklaces as she looked slowly around the room.

“Did I take it back?” she said. “Where’s the flashlight?” Her hands jerked away from the necklaces. “The night traveller!” she whispered. “But no,” she said, “it was Miss Zeely all the time.”

Geeder found the flashlight behind the window curtains. She placed it on her bureau so she would remember to return it to Uncle Ross. Then, she sat down on the bed and picked up two of her glass-bead necklaces. She swung them before her, like pendulums.

“Remember the turtle,” she murmured, “remember the snake.”

She swung the beads back and forth until she grew dizzy from watching the changing light of them. She was hungry again, as she usually was soon after supper. Maybe Uncle Ross had saved her a sweet potato.

“I only had one,” she said. “I was talking so much, I didn’t even taste it.”

A Biography of Virginia Hamilton

Virginia Hamilton (1934–2002) was the author of forty-one books for young readers and their older allies, including

M.C. Higgins, the Great

, which won the National Book Award, the Newbery Medal, and the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, three of the most prestigious awards in youth literature. Hamilton’s many successful titles earned her numerous other awards, including the international Hans Christian Andersen Award, which honors authors who have made exceptional contributions to children’s literature, the Coretta Scott King Award, and a MacArthur Fellowship, or “Genius Award.”

Virginia Esther Hamilton was born in 1934 outside the college town of Yellow Springs, Ohio. She was the youngest of five children born to Kenneth James and Etta Belle Perry Hamilton. Her grandfather on her mother’s side, a man named Levi Perry, had been brought to the area as an infant probably through the Underground Railroad shortly before the Civil War. Hamilton grew up amid a large extended family in picturesque farmlands and forests. She loved her home and would end up spending much of her adult life in the area.

Hamilton excelled as a student and graduated at the top of her high school class, winning a full scholarship to Antioch College in Yellow Springs. Hamilton transferred to Ohio State University in nearby Columbus, Ohio, in order to study literature and creative writing. In 1958, she moved to New York City in hopes of publishing her fiction. During her early years in New York, she supported herself with jobs as an accountant, a museum receptionist, and even a nightclub singer. She took additional writing courses at the New School for Social Research and continued to meet other writers, including the poet Arnold Adoff, whom she married in 1960. The couple had two children, daughter Leigh in 1963 and son Jaime in 1967. In 1969, the family moved to Yellow Springs and built a new home on the old Perry-Hamilton farm. Here, Virginia and Arnold were ableto devote more time to writing books.

Hamilton’s first published novel,

Zeely

, was published in 1967.

Zeely

was an instant success,winning a Nancy Bloch Award and earning recognition as an American Library Association Notable Children’s Book. After returning to Yellow Springs with her young family, Hamilton began to write and publish a book nearly every year. Though most of her writing targeted young adults or children, she experimented in a wide range of styles and genres. Her second book,

The House of Dies Drear

(1968), is a haunting mystery that won the Edgar Allan Poe Award.

The Planet of Junior Brown

(1971) and

Sweet Whispers, Brother Rush

(1982) rely on elements of fantasy and science fiction. Many of her titles focus on the importance of family, including

M.C. Higgins, the Great

(1974) and

Cousins

(1990). Much of Hamilton’s work explores African American history, such as herfictionalized account

Anthony Burns: The Defeat and Triumph of a Fugitive Slave

(1988).

Hamilton passed away in 2002 after a long battle with breast cancer. She is survived by her husband Arnold Adoff and their two children.

For further information, please visit Hamilton’s updated and comprehensive website:

www.virginiahamilton.com

A twelve-year-old Hamilton in 1948, when she was in the seventh grade.

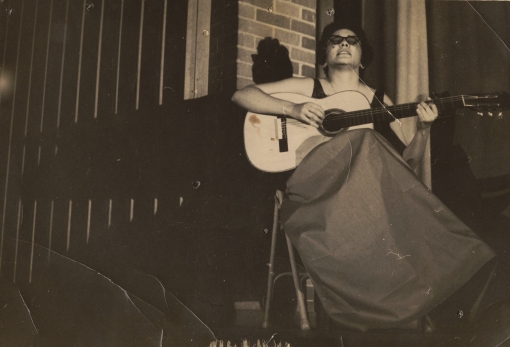

Hamilton at a New York City club while she was a student at Antioch College in the mid-1950s. She often performed as a folk and jazz vocalist in clubs and larger venues.

Hamilton with her brothers, Buster and Bill, and sisters, Barbara and Nina, around 1954.