Zodiac Unmasked (33 page)

Authors: Robert Graysmith

Tags: #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Fiction, #General

was filed in Probate Court showing that he was born in 1928

and

1926.

“A local guy is so convinced that this man is the Zodiac that he started his own book and then went to the television people and hired an attorney.

He was going to blow the whistle on this guy Andrews as a responsible 5 I told him you better be sure—there ain’t no way in hel that I can prove it!

You’re just going to leave yourself wide open for a libel suit. And final y the television people backed off too because I haven’t heard any more about

it from them. Besides, we weren’t able establish that Andrews had any sort of proficiency with guns.” Nervous, temperamental, the suspect once

said, “What I have is better than sex!” He told a Sambo’s Restaurant waitress he was “going to come back and blow her legs off.” “Avery

determined that this man was a student at Riverside City Col ege,” continued Narlow, “but I was never able to confirm that. There’s his apartment in

San Francisco, the one that was supposedly underwater. [On April 20, 1970, Zodiac wrote that the bus bomb he kept stored in his basement had

been a dud. “I was swamped out by the rain we had a while back,” he explained.] He worked at the San Francisco Airport—as a matter of fact he

would have been working there about the time of Cheri Jo Bates’s murder in October 1966. Wel , I’l tel you, if he is not the Zodiac, I’l take one just

like him.”

Two months before the first Zodiac murders, the subject had color-ful y remarked, “I felt the smartest thing I could do would be to pul an Anton La

Vey. He couldn’t make it as a bar organist, so he looked at himself in the mirror one day and said, ‘I am a character.’ Then he hired a press agent

and became Satan. I am a character too, right off the old screen, but I can’t afford a press agent. I am also humble—because I see how absurd this

game is!” Zodiac had written, “I am insane, but the game must go on.”

My friend, Fay Nelson, spoke with Andrews in San Francisco. “His car at the time of the Blue Rock Springs murders was a white Renault

Caravel e, a car similar to the Corvair in appearance.” We learned Zodiac was not this man, but there was a link of sorts—he had a vintage movie

theater. Police thought so too. They compiled a list of everyone who ever worked there. I discovered the fol owing:

The Most Dangerous Game

, a

film that inspired Zodiac, had played there in May 1969. After January 1, 1969, the theater had gone to Friday night showings and Zodiac had

begun attacking on Saturdays. Darlene Ferrin, the Blue Rock Springs victim, had written two names her notebook—“Leigh” and “Vaughn.” Robert

Vaughn was the name of the silent-movie organist at the Avenue Theatre. Both he and Avery’s suspect had worked there since March 1968. Was

this a theater Zodiac frequented regularly? I decided to pay another visit there and find out.

Friday, September 1, 1978

Classic cars parked

on the rain-slick street made the silent-movie palace at 2650 San Bruno Avenue hard to miss. The theater’s large domed

ceiling had once been decorated in a Spanish motif. Now, around a chandelier right out of

The Phantom of the Opera,

an artist had painted al the

symbols of the Zodiac.

Narlow’s suspect managed the theater, existing in genteel squalor to finance his passion for flickering silents and early talkies. He defrayed costs

by exhibiting unique contemporary films. The previous week he had shown a 3-D thril er,

Man in the Dark

. On Fridays “Photoplays and Concerts

with ful Wurlitzer accompaniment” were featured. Fans flocked to these early Pathe Freres Films, D. W. Griffith one-reel Biographs. They adored

stars like Mary Pickford, Lionel Barrymore, Doug Fairbanks, and Buster Keaton.

Waddling like Charlie Chaplin, round-backed, roly-poly, and bandy-legged, the suspect roamed the aisles bel owing “Road to Mandalay.” At any

second his two-hundred-pound, five-feet-eight-inch frame threatened to burst from a tux three sizes too smal . He recited Shakespeare in a

booming voice. The surviving victim at Lake Berryessa had characterized Zodiac’s voice as “like that of a student . . . with some kind of drawl, but

not a Southern drawl.” Andrews admitted that though his own voice was moderate in sound, “that is, not high- or low-pitched, I have something of a

gift of mimicry—I can imitate W. C. Fields and have done both male and female voices on the radio—and I just enjoy what a pompous ass I am. . . .

I may look OK on the outside, but inside . . .”

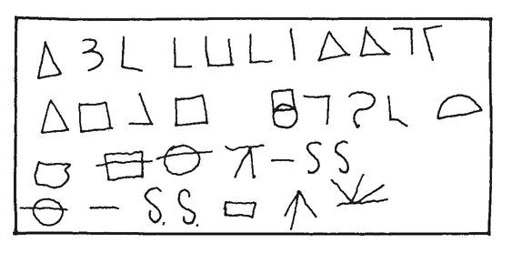

While Vaughn, the organist, pumped on a mighty Wurlitzer pipe organ (Zodiac had mentioned the “piano-oginast” on his “little list” of potential

victims), Narlow and Avery’s interesting find became the projectionist. After the double feature they ripped down a handprinted felt-tip-pen poster

advertising “The Big Parade with John Gilbert and Renee Adoree.” Someone at the theater drew them for the constantly changing bil s. I retrieved

another from the gutter and took it to Morril in Sacramento. He studied the handprinting. “With the exception of the three-stroke

K

it’s a good

match,” he said, beaming. “That’s the closest Zodiac lettering I’ve seen!” Not only might the theater’s discarded posters have provided Zodiac with

his alphabet of printed letters, but the Academy Standard leader on each strip of film was fittingly a crossed circle.

Wednesday, October 17, 1978

I drove over

the Golden Gate Bridge toward Santa Rosa in a steady downpour. I stopped along the way and parked amongst the gray

warehouses where the theater manager had once kept his warren of connected apartments. The building had been redone and repainted, the old

line of mailboxes in the courtyard taken down, and his gadget-cluttered rooms (movie equipment, theater seats, rows of 35-mm monochrome film-

processing machines) emptied. Time was marching on and Zodiac was no closer to being caught than a decade ago.

Leigh was nowhere around his trailer when I got there. Eighteen days earlier he had ceased instal ing home security devices and quit his job as a

senior-citizen aide in Val ejo. “Could Narlow and Avery’s suspect and Leigh Al en be working together?” a policeman suggested to me. “Check out

the possibility, however remote, that there is a connection between the two.” The thought of some sort of Zodiac confederate was never far from my

mind. I had noticed the odd spacing in the Zodiac letters: “He plung ed him self . . . wand ering.” It reminded me not only of sign painters who did

one letter at a time, but someone taking dictation, writing each syl able as they came, stringing them together like a cars on a train and with no

regard to sense.

Thursday, October 18, 1978

Bill Armstrong retired

from the SFPD. “I could feel the fire had gone away,” Toschi said of his partner. “I remember, when he left Homicide in late

’75, he told me, ‘Toschi, I’ve stood over my last body.’ However, the fire was stil burning inside me.” The same day Al en begrudgingly began

seeing a mental health professional.

As a condition of his release from Atascadero, Leigh had been required to see Dr. Thomas Rykoff, a Santa Rosa psychiatrist6 Prior to their first

meeting, Leigh, as he had in prison, probably combed the library. In the 1960s he asked Cheney, “Are there books on how to disguise your

handprinting and change your appearance?” Cheney said, “I’m sure they exist.” It made sense he would now bone up on proper responses to

psychiatric tests. Under present law, a fragmented man such as Zodiac could not be considered legal y insane. Dividing “sane” from “insane”

becomes difficult with “murderers who seem rational, coherent, and control ed,” wrote Dr. Joseph Satten, “and yet whose homicidal acts have a

bizarre, apparently senseless quality.”

Unlike schizophrenics, a sexual sadist such as Zodiac “does not exhibit obvious aberrations, but takes considerable pains to appear normal and

avoid capture. Of al murderers, he is most likely to repeat his crime.” After the first kil ing, these intel igent kil ers become amazingly proficient at

concealing themselves. They take great pains to appear normal, but often perversely throw suspicion upon themselves. The cat-and-mouse game

with the police eventual y becomes the principal motive for the crimes. Behind a smiling, secretive facade, he feels vastly inferior, hostile, anxious,

and persecuted. Yet that perverse urge to cal attention to himself as Zodiac is an itch almost impossible not to scratch. Or was Leigh’s secret that

he only

thought

he was Zodiac?

No one knows what creates a compulsive kil er—a missing sex chromosome? —an event during the first six months of life? Whatever the cause,

the condition is incurable. Cruel, rejecting parents and peers create pressures expressed in childhood by bed-wetting, shoplifting, and animal

torture. With the awakening of puberty, the anger manifests itself in ever-increasing and cleverly concealed acts of sadism. Sheriff Striepeke’s

privately commissioned psychological profile stated Zodiac was a white, unmarried man under thirty-five years old “who tortured animals, had a

passive father and dominant mother, and may have spent time in a mental institution.” Meanwhile, Leigh Al en continued to day-dream in his trailer

and basement. Dwel ing in an escapist world of science fiction and the occult, arrogantly intolerant of people, he tended to set his own rules. “I’ve

been able to personal y study several of these [serial kil ers] very closely,” Dr. Lunde told me. “Bianchi’s responses on psychological tests are

almost verbatim like Kemper’s. The whole sort of thing of seeing animals torn apart and blood and animal hearts.”

A psychologist working under conditions of Al en’s parole evaluated Rykoff’s tests and findings. When he gave the suspect a projective test, a

Rorschach (ink blot) test, Rykoff was warned to look for answers that contained the letter

z

. “The odds of more than one answer beginning with

z

are very remote,” the analyst told detectives before the Rorschach test. “I don’t expect any.” The first two mirror images Leigh was shown reminded him

of “a zygomatic arch.” The analyst was shaken by this. He went on. “What do you see in this?” At the end of the tests, he found that Al en had given

five

z

responses, far outside the norm. Cabdriver Paul Stine had been wounded in the zygomatic arch by Zodiac.

A doctor’s report on Leigh had said, “He’s potential y violent, he is dangerous,” and “he is capable of kil ing.” The same analyst thought Al en had

“five separate personalities.” Split personalities would explain how he passed a lie-detector test; why his handprinting did not match Zodiac’s. The

psychiatrists’ conclusions were mounting: Leigh “is extremely dangerous and is a sociopath . . . is highly intel igent and incapable of functioning with

women in a normal way . . . has a potential for danger.” In their private sessions, Dr. Rykoff discovered the violent side of his new patient’s nature.

Any kind of accusation set him off. The subject of his mother or prison enraged him. Leigh became defensive, shaking with anger until he regained

control, then became sarcastic. His remarks, icy, though witty, were packed with puns and double meanings. Immature, self-centered, with a strong

ego, he had a taunting way of speaking, but was capable of great personal charm. When Al en spoke of Zodiac, he felt persecuted. Worst of al , he

cried—long heartrending moans. Between sobs, Dr. Rykoff felt Al en was “repressing very deep hatred.” But on another level Leigh aced every

perception test from blocks to puzzles. “This guy can look at something, figure it out in a matter of minutes, and do it with the least amount of energy

and effort,” one expert had said. “And he laughed at other people for stumbling through the same task.” Al en took his psychiatric tests under duress

and always in the same manner: “He would not smile or show emotion and would speak in a low, measured monotone.” Al en’s parole officer,

Bruce Pel e, came to know this menacing, focused monotone wel .

Rykoff’s sessions with Al en were conducted as a favor to Lieutenant Jim Husted of the Val ejo P.D. and Pel e. Rykoff was in the middle of

studying Leigh when a new patient was signed on—a young woman. She desired to be hypnotized as part of a training program for a social

rehabilitation group she was organizing in Santa Rosa. Rykoff welcomed her, unaware that she was Leigh Al en’s sister-in-law, Karen. Whether or

not the police suggested Karen see the same therapist as her brother-in-law is open to speculation. But Husted, head of the Intel igence Unit, was

wily. Through his manipulation or not, somehow Karen ended up with Rykoff. During their sessions she remarked about a chemist brother-in-law

and his dark side. Rykoff saw the man constantly preyed on her mind. As Karen expounded more of her impressions and suspicions, Rykoff began

to realize the character she was sketching seemed familiar.

“He spoke of man as true game,” she said. “Once he and his brother got in an argument over dinner. He leaped on him and began choking him.”

“What’s this?” thought Rykoff. “That sounds just like Arthur Leigh Al en. The potential for danger is just the same.”