Zom-B (7 page)

But he did emerge in the end, and I saw a Muslim guy glowering behind him. Dad pointed to me and said, “That’s who I fight for—my kid, my wife, my friends. Anything ever happens to any of them, I’ll come back here and burn the lot of you down to the ground.”

Then Dad hugged me hard. I glared at the Muslim and shot him the finger. Dad laughed, clapped my back, took me for dinner and bought me the biggest hamburger I’d ever seen. I felt bad about it afterwards but at the time I was on cloud nine.

Part of me knows I should stop acting, that I’m on thin ice, growing less sure of where the actor ends and the real me begins. When I grunted at Nancy, that wasn’t part of an act. That came from the soul.

I should tell Dad I don’t share his views, that I’m not warped inside like he is, start standing up to him. But how can you say such a thing to your father? He loves me, I know he does, despite the

beatings when he’s angry. It would break his heart if I told him what I really thought of him.

Dad doesn’t like to be disturbed when he’s discussing the state of affairs with his friends and associates, so even though I’m hungry, I slide on by the kitchen, planning to head straight to my room. But Dad must hear me because he calls out, “B? Is that you?”

“Yeah.”

“Come here a minute.”

He sounds more subdued than usual. That tips me off to the fact that there might be somebody important with him. Dad’s loud and bullish most of the time, but quiet and submissive around people he respects.

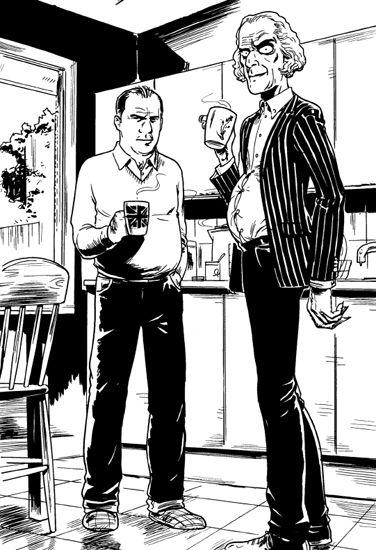

I head into the kitchen, expecting someone in a suit with a politically perfect smile. But I stagger to a halt halfway through the door and stare uncertainly. The guy with Dad is like nobody I’ve ever seen before.

The man is standing by the table, sipping from a cup of coffee. He sets it down when he spots me and arches an eyebrow, amused by my reaction.

He’s very tall, maybe six foot six, and thin, except for a large potbelly. It looks weird on such a slender frame, and the buttons on the pink shirt he’s wearing beneath his striped jacket strain to hold it in. He has a mop of white hair and pale skin. Not albino pale, but damn close. Long, creepy-looking fingers.

But it’s his eyes that prove so startling. They’re by far the biggest I’ve ever seen, at least twice the size of mine. Almost totally white, except for a dark, tiny pupil at the center of each. As soon as I see him, I immediately think,

Owl Man

. I almost say it out loud, but catch myself in time. Dad would hit the roof if I insulted one of his guests.

“So this is the infamous B Smith,” the man chuckles. He has a smooth, cultured voice. He sounds like a radio presenter, but one of the old guys you hear on a Sunday afternoon on the station your gran listens to.

“Yeah,” Dad says. He runs a hand over my head and smiles as if he’s in pain and trying to hide it. “How was school?”

“Fine,” I mutter, unable to tear my gaze away from Owl Man’s enormous, cartoonish eyes.

“Some people think it’s rude to stare,” Owl Man says merrily, “but I’ve always considered it a sign of honest curiosity.”

“Sorry,” I say, blushing at the polite rebuke.

“No need to be,” Owl Man laughs. “The young

should

be curious, and open too. You should have nothing to hide or apologize for at your tender age. Leave that to decrepit old warhorses like your father and me.”

Dad clears his throat and looks questioningly at Owl Man. “Anything you’d like to ask?” he says meekly.

“Not just now,” Owl Man purrs and waves a long, bony hand at me. “You may proceed. It has been nice seeing you again.”

“Again?” I frown, certain I’ve never met this guy before. There’s no way I could have forgotten eyes like that.

“I saw you when you were a child. You were a cute little thing. Sweet enough to eat.”

Owl Man gnashes his teeth playfully, but there’s nothing funny about the way he does it and I get goose bumps up my arms and the back of my neck.

“I’m going to my room,” I tell Dad and hurry out without saying anything else. I half expect Dad to call me back and bark at me for not saying a proper good-bye, but he lets me go without a word.

I find it hard to settle. I keep thinking about the guy in the kitchen, those unnaturally large eyes. Who the hell is he? He doesn’t look like anyone else my dad has ever invited round.

I surf the Web for a while, then stick on my headphones and listen to my iPod. I shut my eyes and bop my head to the music, trying to lose myself in the tunes. Sometime later, opening my eyes to stare at the ceiling, I spot Owl Man standing just inside the door to my room.

“Bloody hell!” I shout, ripping off the headphones and sitting up quickly.

“I did knock,” Owl Man says, “but there was no answer.”

“How long have you been standing there?” I yell, trying to remember if I’d been scratching myself inappropriately over the last five or ten minutes.

“Mere moments,” he says, his smile never slipping.

“Where’s my dad?” I ask, heart beating hard. For a crazy second I think that the stranger has killed Dad, maybe pecked him to death, and is now gearing up for an attack on me.

“In the kitchen,” Owl Man says. “I had to come up to use the facilities.”

He falls silent and stares at me with his big, round eyes. At the back of my mind I hear Mum reading that old fairy tale to me when I was younger.

All the better to see you with, my dear.

“What do you want?” I snap, not caring about insulting him now, angry at him for invading my privacy.

“I wanted to ask you a question.”

“Oh yeah?” I squint, wondering if he’s going to make a pass at me, ready to scream for Dad if he does.

“Do you still have the dream?” he asks, and the scream dies silently on my lips.

“What dream?” I croak, but I know the one he means, and he knows that I know. I can see it in his freakish, unsettling eyes.

“The dream about the babies,” Owl Man says softly. “Your father told me that you had it all the time when you were younger.”

“Why the hell would he tell you something like that?” I try to snap, but it comes out more as a sob.

“I’m interested in dreams,” Owl Man beams. “Especially dreams of monstrous babies.

mummy

,” he adds in a high-pitched voice, and it sounds just the way the babies in my nightmare say it.

“Get out of my room,” I moan. “Get out before I call my dad and tell him you tried to molest me.”

“Your father knows I would never do anything like that,” Owl Man sniffs and takes a step closer. “I’m not leaving until you tell me.”

“No,” I spit. “I don’t have it anymore, okay?”

Owl Man studies me silently. Then his lips lift into an even wider, sickening smile. “You’re lying. You

do

still have the dream. How interesting.”

The tall, thin man pats his potbelly, then presses his fingers to his lips and blows me a kiss. “Good evening, B. It has been a pleasure meeting you again after all these years. Take care of yourself. There are dark times ahead of us. But I think you will fare well.”

With that he turns and slips out of my room, carefully closing the door behind him. I don’t put my headphones back on. I can’t move. I just lie on my bed, think about his enormous eyes, wonder at the nature of his questions and shiver.

I don’t see much of Dad over the next few days. It’s like he’s avoiding me. I want to ask him about the strange visitor, find out his real name, where he’s from, why he was here, why Dad told him about my dreams. But Dad clearly doesn’t want to discuss it, and what Dad wants, Dad gets.

So I say nothing. I keep my questions to myself. And I try to pretend that my surreal conversation with Owl Man never happened.

On Friday we visit the Imperial War Museum. I’ve been looking forward to this for weeks and my spirits lift for the first time since my run-in with Nancy and the rest of that bizarre afternoon. We don’t go on many school trips—the money isn’t there, plus we’re buggers to control when we’re let loose. Twenty of our lot were taken to the Tate Modern last year and they ran wild. The teachers swore never again, but they seem to have had a change of heart.

“I don’t expect you to behave like good little boys and girls,” Burke says on the Tube, to a chorus of jeers and whistles. “But don’t piss me off. I’m in charge of you and I’ll be held accountable if you get out of hand. Don’t steal, don’t beat up the staff, and be back at the meeting point at the arranged time.”

“Do we get a prize if we do all that, sir?” Trev asks.

“No,” Burke says. “You get my respect.”

I love the War Museum. I was here before, when I was in primary school. We were meant to be looking at the World War I stuff, but the tanks and planes in the main hall are what I most remember.

“Look at the bloody cannons!” Elephant gasps as we enter the gardens outside the museum. “They’re massive!”

“You can have a proper look at them later,” Burke says.

“Aw, sir, just a quick look now,” Elephant pleads.

Burke says nothing, just pushes on, and we follow.

The main hall still impresses. I thought it might be disappointing this time, but the tanks and planes are as cool as ever. The planes hang from the ceiling, loads of them, and the ceiling’s three or four floors high. Everyone coos, necks craned, then we hurry to the tanks. They’re amazing, and you can even crawl into some and pretend that you’re driving them. We should be too old for that sort of stuff, but it’s like we slip back to when we were ten years old—the lure of the tanks is impossible to resist.

Burke gives us a few minutes to mess around. We’re the second group from the school to arrive. As the third lot trickle in, we form a group and head upstairs to where the Holocaust exhibition starts.

This is the reason we’re here. We haven’t focused much on the Holocaust in class–at least not that I remember, though I guess I could have slept through it–but our teachers reckon this is important, so they’ve brought us anyway, regardless of the very real risk that we might start a riot and wreck the place.

Burke stops us just before we go in and makes sure we’re all together.

Kray sniffs the air and makes a face. “Something’s burning.”

I expect Burke to have a go at him, but to my shock it’s Jonesenzio–I didn’t even know he was here–who speaks up.

“One of my uncles was Polish. He was sent to Auschwitz in the thirties. Not the death camp, where they gassed people, but the concentration camp. He was worked like a slave until he was a skeleton. Starved. Tortured. The bones in one of his feet were smashed

with a hammer. He survived for a long time, longer than most. But in the end he was hung for allegedly stealing food from a guard. They let him hang for nearly ten minutes, without killing him. Then they took him down, let him recover, and hung him again until he was dead.”

Jonesenzio steps up to Kray, stares at him until he looks away, then says softly but loud enough for everyone to hear, “If there are any more jokes, or if you take one step out of line from this point on, you’ll have to answer to

me

.”

It should be funny–pitiful even–but it isn’t. Everyone shuts up, and for the first time that I can ever remember, we stay shut up.

The exhibition is horrible. It’s not so bad at the start, a bit boring even, where we learn about the buildup to war, how the Nazis came to power, why nobody liked the Jews. But it soon becomes a nightmare as we dip further into the world of ghettos, death camps and gas chambers.

Old film footage of Jews being rounded up and chased by Nazis hits hard. So does the funeral cart on which piles of corpses were wheeled to mass graves. And the rows of shoes and glasses, taken from people before they were gassed and cremated.

But what unsettles me most is a small book. It belonged to a girl, my sort of age. She wrote stories in it and drew sweet, colorful pictures. As I stare at it I think,

That could have been me.

Sitting in my room, writing and drawing. Then dragged out, shipped off to a death camp in a train, shaved bare, stripped naked, gassed, cremated

or buried in an unmarked grave with a load of strangers. And all that’s left of me is a stupid book I used to scribble in, in a cold, empty room where no one lives anymore.