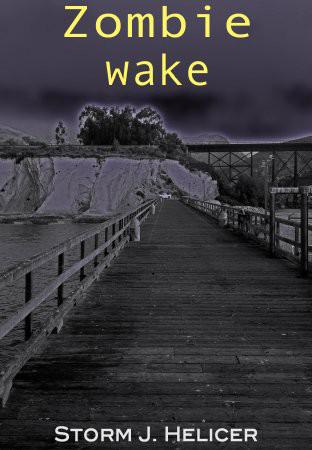

Zombie Wake

Authors: Storm J. Helicer

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Short Stories, #Single Author, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Post-Apocalyptic, #Single Authors

Zombie Wake

By Storm J.

Helicer

Zombie Wake

Copyright © 2013 by

Storm J.

Helicer

All Rights Reserved. Apart from

fair use, no portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored or

introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any

means without prior written permission of the publisher. Contact us at

[email protected]

This is a work

of fiction. Incidences, names and characters are not factual accounts.

What has transpired since I closed

the gates at sunset, since the light from the sun was replaced with the glow of

sodium lamps, is something I'm sure even the beady eyes of the bird to my side

knows as atrocity.

In my career as a park ranger,

aside from a feral pig eradication project, I have only discharged my weapon at

the range. I've been a park ranger for almost ten years now, all of it at

California’s

Gaviota

coast. I was looking forward to

having a full career here—life and family too. I didn't know it would end

like this. How could I know, it's been three hours. Today seemed normal. Now I

stand at the end of the pier, my only witness a brown pelican.

Earlier, as I patrolled the pier,

the familiar fish odor wafted in bursts. The pelican perched on the rail, as it

does now with tar smudged across its chest, eyed fishermen for handouts. I've

seen a thousand brown pelicans in this ocean park, but none with such a

prehistoric likeness. Its beak, on the shorter side of average, tells me it,

she, is female. Though, the tip looks like a curved tooth; like the tooth a

chick uses to emerge from its egg. This pelican, however, is fully mature.

I first noticed her this morning

when she outstretched her wings gaining an ominous stature. Lifting off the

railing with one flap she propelled toward the ocean, circling to make her way

to a new station. Positioning herself next to a yellow vinyl rope tied around

the splintered wooden beam, the bird pointed her tooth toward the rope's

origin, a black mesh metal basket containing three fish.

I stepped toward

Makimo

, who is nearly a resident here. Her hands, in yellow

rubber gloves, fed the rope one over the next, raising the dangling basket to

show me her catch. The fish gleamed blue and green along the top, silver on the

bottom. The largest lay motionless on its side, eyes bulging and glassy. The

two smaller fish flopped, arcing their spines like they were trying to keep

time with a high frequency wave.

“These are for the cat. I keep them

fresh,” she gusted. The water below was unusually murky-brown. Small waves

sloshed and foamed around the pilings. “I saw your son yesterday playing on the

swings. He’s tall for a little guy. He’s

gunna

be big

like you?”

“We'll see

Makimo

,”

I said.

*

But at this moment in the cold, wet

night air I don't—can't—take time to contemplate. My training, my

muscle memory, at the instant when I make my way to the end of the pier,

take

over.

The first one I shoot, I recognize.

Not his face or clothing, those are too drenched with blood, scabs and froth.

It's the thumb, the plum thumb as I had referred to it this morning that I

notice. Earl.

I had come into contact with him

twice in the last month. The first was for illegal camping. He was under the

pier, sitting on the sand, stick in hand, leaning against a piling, poking into

a small fire.

Four college-aged boys pointed him

out to me after a short conversation through my open truck window. They were

walking with fishing poles and chuckling. Their faces sobered as they noticed

my white truck. Three of them gave me what I call the straight smile, a slight

smile with a glance downward. I receive the look occasionally when off duty but

often while in uniform. I have a theory that it has to do with a primal male

dominance/subordinate behavior. Normally my height of six foot eight inches

attracts looks, questions and the like, but the vest adds a bulk, not intrinsic

to my body type, that must make me seem... intimidating. Since I generally make

a habit of telling goofy jokes and wild stories, rapport with the public has

never been a problem.

“How's the fishing,” I asked

through my truck’s window.

“Not so good today,” said the one

raising a green cooler to the tip of his index finger.

“Then, it

ain’t

the fishing that's bad, it's the catching. Besides, someone’s

gotta

make sure the pelicans have fish left to eat.”

And so it happened that the brief

conversation with the boys ended with the story of the man under the pier. He

had approached them trying to sell what he called Indian marijuana. They said

he was stubborn and wouldn't take no for an answer.

A few minutes later, I stood at the

foot of the fire, speaking into the radio, “R1122, I need a wants and warrants

check on one, ID in hand, first of Earl: Edward, Adam, Robert, Lincoln, second

of

Dunkle

, David, Union, Nora, King, Lincoln, Edward;

DL number CA0076487.” Earl had voluntarily emptied the contents of his pockets,

a crunched up paper bag filled with large white trumpet shaped flowers, toxic

Jimsonweed, a wallet, and a black comb.

While I waited for the response,

Earl inhaled his cigarette with force, which is often a sign of outstanding

felony warrants. I widened my stance and looked toward his hands. Seeing my

eyes on his thumb, he said, “Man, I'm just trying to make a buck. You know the

Chumash drink it as a tea. They're just flowers. Listen, I've had a pretty

shitty go of it.” Holding up the purple plum, he went on. “It's been nearly two

years, I wish they'd cut it off. I was up in Alaska on a crab boat. I went to

grab a cage and my thumb got caught in the winch. The thing took off all my

skin down to the bone. I didn't have any insurance and still the doctors

decided to save it—got an old doctor, treated guys on the field in World

War II. So they cut a slit here in my belly and sewed my thumb in it.” He

lifted up his shirt and ran his good thumb down the scar. “When they took it

out three months later, it was like this. Look.” He pushed the bulb toward me.

“There's a nail in there I can't even cut. I can't do a damn thing with it. The

whole hand hardly works and it's throbbing all the time.”

*

He had changed significantly in the

two days since I last saw him. He was walking with both hands outstretched,

like the thumb was guiding him. Even though we're trained to shoot for the

heart and head, it was the hands my first bullet hit. Shooting the hands occurs

frequently in simulated gunfire trainings. The “victims” walk away from these

trainings with paint blotches all over the chest, head and hands. I didn't

notice it was Earl as an individual until I pulled the trigger and saw the red

spatter and flying fingers.

With the rest, distinguishing

anyone was next to impossible. They, more like

it,

was

one mass, traveling like molasses,

rolling down the hill through the campground. There were two groups, one from

the east and another from the west. In the parking lot, they merged. I knew the

campground was at capacity but it seemed like the number moving toward me was

more than the 450 person upper limit. I was too far away from my vehicle to

make my way through the sea of scabs and froth.

Just over a week ago, I dressed in

the dark to respond to a vehicle collision. Car accidents are too much of my

occupation these days. Because

the park is bordered by a

major highway

, California’s Highway 101, rangers are often the first on

scene arriving ahead of the highway patrol, fire, and ambulance. That day, just

north of the campground, during the first rain of the season, a bus slid off the

road. It was probably the most gruesome accident I have witnessed. Just south

of the

Gaviota

tunnel the road juts to the left. In a

depression where the road curves, a pool of water gathers every rain. Year

after year, cars speeding through that section of road hit the puddle and veer

off, sliding, spinning, and sometimes going over the edge. A similar sequence

of events occurred with this bus.

It was a short, blue and white bus

with thirteen passengers, the driver and twelve patients. Traveling north, from

Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital to Stanford Medical Center, the bus, the highway

patrol concluded later, hit the water, slid across three lanes of highway,

rolled as the tires made contact with the center clearing, slid on its side

taking two sedans from the southbound side and pushed them all over the

embankment. The bus itself stopped short of going over the edge. But two sedans

plunged twenty feet into the creek, which flowed fast with fresh mountain rain.

I was the first on scene.

I don't know if you need a certain

personality type to deal with these situations, or if the training we receive

teaches the detachment needed to get through them. Or if, eventually, there

will be some kind of ramification. Either way, I went into the deliberate mode

that I’ve also heard other peace officers speak about.

Bodies spilled out of the vehicle,

some on the ground and some partway through the window, with muddy skid marks

pointing over a twenty-foot drop, all reflected in the blue/red

strobing

lights of my patrol truck. Into the radio I said,

“R1122 on scene. I have an incident involving a full bus. It is a multiple

victim incident. We need expanded response, multiple AMR response. Call out

L855 for aquatic rescue. Begin critical incident notifications. I'm going to begin

triage and will provide updates as possible.” I heard the female voice respond

with a tone equally flat, “R1122, I copy. I will relay by landline to county.”

Feeling the rain on my head start

to run down the back of my neck under my green rain gear, I made a conscious

effort to keep my hands from flipping my hood over my head. I couldn’t spare

time. Instead, I unzipped the red first aid bag sitting in the backseat of my

truck, pulled two latex gloves over my wet hands and grabbed a handful of tags:

green, yellow, red and black.

By the time I heard Dylan's voice,

I had tagged everyone on the freeway and had scrambled down the embankment into

the creek. I was sliding knee deep in mud, looking down the creek where the

beam of my flashlight had fallen on a large woman's naked body half submerged

and pinned against tree roots when I heard a shout in the distance, “Storm.”

Slowing my forward movement, I grabbed a sapling and turned. Seeing that Dylan

and Joe were suited in their swift water gear jolted me back into my thinking

head. I wondered if I was going to let myself step into the water, a maneuver

that could be devastating and something I knew better than to attempt. But the

motion my hand made, reminded me of my current objective. “R1122” I said into the

radio. Dispatch didn't echo.

Reception was unreliable near the

tunnel and in the creek there was none. I started to reach for my cell phone

then turned toward Joe and Dylan, who were following a line, making their way

down. I could see the reflection of the bag, the source of the rope, which had

been thrown to a position in front of a large boulder nearly twenty yards from

me. Aside from their reflective yellow vests and helmets, they resembled

burglars with their dark wetsuits and booties. Waving to them with my

flashlight, I motioned up stream.

By this point I was amazed to see a

survivor. Up on the road, every person I evaluated was a black tag. Blood, and

grey fluid oozed from heads and noses. Two victims of the bunch appeared

completely intact but their

pulseless

necks secured

them the dark label. I spent too long searching one woman’s soft neck. Through

my gloves, the skin felt unusually warm—though my hands were icy cold.

She was one of the few remaining in the vehicle, buckled into the dark vinyl seats,

the backrest high enough to minimize neck injury. In that compartment's dome

lighting, her face looked too alive. I have heard of situations where the

physical impact of the accident is enough to sheer the aortic valve from the

heart leading to instantaneous, mark-free death. I wondered if this was the

case. Then reminded myself that I'm not a doctor, that my job is to show the

EMT which victims to start with, which victims have a chance. But there was

something about the lady that made me linger. Moving her hair from her neck, I

noticed that she had what appeared to be a reverse dye job, the roots were

black for inches, then the remainder of the hair, grey. After trying three

times to find any sign of life, I gave up and looped the elastic band with tethered

black tag around her head.