100 Most Infamous Criminals (21 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

Louis Lepke

L

ouis Lepke, the boss of the Jewish arm of Murder Incorporated, is the only American Mafia chieftain to have been executed. After two years hiding out in Brooklyn, he gave himself up to the FBI, persuaded into doing so, it’s said, by Albert Anastasia. He, Lucky Luciano and the other members of the Syndicate wanted him dead.

Lepke, short for ‘Lepkele’ or ‘Little Louis’, was born Louis Buchalter in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in 1897. His father, the owner of a hardware store on the Lower East Side, died of a heart attack when he was 13, and his mother moved soon afterwards to Colorado. Little Louis, then, came of age in the streets. He hung out with hoodlums, and was soon in trouble with the law. He was sent out of town to live with his uncle in Connecticut, and then to a reformatory, from where he soon graduated, around the time of his 21st birthday, first to New York’s Tombs prison, and then to Sing Sing, where he acquired the nickname ‘Judge Louis’.

Back on the streets again in 1923, he went into the protection business with an old pal, Joseph ‘Gurrah’ Shapiro – they were known as ‘the Gorilla Boys’ and specialized in bakeries. But they didn’t hit the big time until they went to work for Arnold Rothstein, who dealt large in liquor and drugs. Soon they were moving into the union rackets, backing the workers against the bosses with goon squads, and then taking over from both. They started out in this with a real expert, ‘Little Augie’ Orgen, as their principal mentor. But by 1927, Orgen simply stood in their way. So on October 15th, they gunned him down in front of his clubhouse and by the beginning of the ’30s they ruled the labour roost: they controlled painters, truckers and motion-picture operators; they were expanding their drugs business; and they still took in $1.5 million a year from bakeries. They were now known, not as ‘the Gorilla Boys’, but ‘the Gold Dust Twins’.

In 1933, with the setting up of the Syndicate, Lepke became a board-director and one of the founding members of Murder Incorporated, its enforcement arm of contract-killers, among whom was a Brooklyn thug called Abraham ‘Kid Twist’ Reles. That same year, though, Lepke was indicted by a federal grand jury for violation of anti-trust laws. And though he ultimately beat the rap on this one, the Feds began closing in with narcotics charges, and the Brooklyn DA’s office with an investigation into racketeering. In the summer of 1937, he – along with ‘Gurrah’ Shapiro – went on the lam; he soon became the most wanted man in US history.

Louis Lepke, one-time boss of the Jewish arm of Murder Incorporated

He did his best from hiding to silence the potential witnesses against him, but the heat on the streets became too great and, in August 1940, he gave himself up, with the understanding that he’d face federal narcotics charges rather than a state indictment for murder. He was sentenced to fourteen years and shipped to the penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas.

Then, though, Abe Reles, ‘Kid Twist,’ one of the executioners he’d hired in the old days, began to sing. For six months Reles was held at a hotel in Coney Island as he gave evidence at trial after trial. On November 12th 1941, his body was found – apparently he’d jumped from a sixth story window – but it was too late for Louis Lepke. For Reles had already appeared before a grand-jury hearing to give evidence against him, evidence that could be – and was – used in court.

Louis Lepke and two of his lieutenants, Mendy Weiss and Louis Capone, were tried for murder and condemned to death. They went to the electric chair in Sing Sing prison on March 4th 1944. The murder of Reles – which got Albert Anastasia and Bugsy Siegel off the hook – was probably arranged by Frank Costello.

Timothy McVeigh

I

t was one of the most devastating crimes in all US history. A hundred and sixty-eight people were killed and more than five hundred wounded, among them twenty-five children under 5. So on April 19th 1995, when the dust finally settled on what remained of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, it was taken for granted that its bombing had been the work of international terrorists. It wasn’t – as those who recognized the symbolism of the date soon realized. For April 19th was Patriots Day, the anniversary of the Revolutionary War battle of Concord. It was also the second anniversary of the fiery and bloody end of David Koresh’s Branch Davidian sect at Waco, Texas. The bomber wasn’t Arab at all, but American: a twenty-seven-year-old ex-soldier from Pendleton, New York called Timothy McVeigh.

McVeigh had been resourceful enough in gathering the materials that made up his huge bomb: a mixture of fuel oil, ammonium nitrate and fertilizer. But he was careless and stupid with everything else. For within an hour and a half of its explosion, he was stopped by a state trooper 75 miles away for driving his getaway car without a licence plate. The trooper then noticed a gun in the car and arrested him. He was taken to jail in Perry, Oklahoma.

It’s possible that he still might have got away – and disappeared – if the identification number of the 20-foot-long Ryder truck he’d armed with the bomb hadn’t been recovered. The FBI traced it to a hire-firm in Kansas where they were able to get a description of the man who’d rented it. Transformed into a sketch by FBI artists, this description was soon recognized by the owner of a motel in Junction City, who was able to pass on the name in his register – incredibly enough, McVeigh’s own. From that point on, it was plain sailing. The name Timothy J. McVeigh was logged into the National Crime Information computer, which revealed that he was under arrest in Perry on an unrelated charge. From there it just took a phone call.

The question people came to ask, then, was no longer ‘Who?’, but ‘Why?’ And the answer travelled deep into the paranoid, poor-white underbelly of American power.

Timothy McVeigh was a classic case of the angry, antisocial loser who blamed his own inadequacies on a conspiracy designed to keep him down. He came from a broken family; lived with a father who didn’t much care for him; and failed to be remembered at school. He enrolled for a while at the local community college, but soon dropped out for a menial job at Burger King. It was only when he applied for a gun licence and moved to Buffalo, New York, to become an armoured-car guard there, that he finally found what seemed to be the only passion he ever really had in his life: guns.

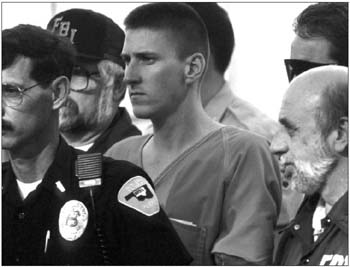

McVeigh’s crime shocked America to its core

That he then joined the army seems now, in retrospect, a natural enough progression. He trained at Fort Benning, Georgia, where he met two equally needy men who later became co-conspirators in his bombing: Terry Nichols and Michael Fortier. It was they, perhaps, who introduced him to William L. Pierce’s fiercely anti-Semitic

The Turner Diaries

, one of the bibles of American white supremacists. The story concerns a soldier in an underground army who, in response to efforts to ban private ownership of guns, builds a fertilizer-and-fuel oil bomb packed into a truck to blow up the FBI building in Washington…

McVeigh became a gunner and served with some distinction in the Gulf War. But when he failed in later tests to become a member of Special Forces, he left the army and became a drifter. He stayed for a while with his two army buddies, Fortier and Nichols, in Arizona and Michigan respectively. But mostly he lived out of his car, collecting gun magazines, attending gun fairs and railing against blacks, Jews and the hated Federal government. In 1993, he even went to Waco, Texas during the Branch Davidian sect’s initial standoff with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. He sold bumper stickers there which denounced the government for trying to take away the nation’s guns.

What subsequently happened at Waco was the trigger that set off the Oklahoma bomb. For McVeigh now determinedly entered what he called the ‘action stage.’ Together with Fortier and Nichols – and with

The Turner Diaries

as a guide – he mapped out his plan: to use a massive bomb against the federal government as revenge, warning and call to arms. Though Fortier, and later Nichols, both dropped out of a final commitment, he didn’t care. He drove the Ryder truck to Oklahoma City and then left a sign on it saying that it had a flat battery, so that it wouldn’t be towed away.

When arrested in Parry, McVeigh – true to form – insisted on calling himself a prisoner of war. He was tried and sentenced to death.

Charles Manson

F

rom the age of 9 until he was 32, Charles Manson, born illegitimate, spent almost all his life in institutions, though he did spend enough time on the outside to be sent down for armed robbery (at 13), homosexual rape (at 17) and car stealing, fraud and pimping (at 23). In prison for this last set of offences, he became, by an odd coincidence, the protégé of another killer, Alvin Karpis of the notorious Barker Gang, who taught him the guitar well enough for him to be able to boast later:

‘I could be bigger than the Beatles.’

In a way, of course, Manson was. For, let out of prison in 1967, the year of ‘the summer of love,’ he became the most hated and vilified figure in America, a symbol of everything that had gone wrong in the ’60s.

Emerging from San Pedro prison with little more than a beard, a guitar and a line in mystic hocus-pocus, Manson was soon playing hippie Jesus on the streets of nearby Haight-Ashbury to a group of adoring disciples – most of them middle-class drop-outs who lived on a diet of hallucinogenic drugs and acted out their fantasies in sex orgies. It wasn’t long, though, before he decided his ambitions were too big for San Francisco. So he took his ‘Family’ south, picking up new acolytes on the way, and settled in the grounds of the Spiral Staircase club in Los Angeles, where he began to attract the attention of the wilder fringes of the Hollywood party scene: musicians, agents and actors looking for kicks or black magic – or the next big thing.

Manson’s vision, though, by this time was becoming darker, more apocalyptic, and by the time he moved the ‘Family’ to the Spahn Movie Ranch 30 miles from the city, he was no longer interested in merely sex, drugs and adoration. He believed that there would soon be a nuclear day of reckoning, called Helter Skelter. He drew up a death list of people he envied or wanted revenge on (‘pigs’ like Warren Beattie and Julie Christie) and he became obsessed with the idea of a dune-buggy-riding army of survivalists which would escape into the Mojave Desert.

To set up this army – and its transport – he, of course, needed money. So, like a latter-day Fagin, he set his ‘Family’ to crime: drug-dealing, theft, robbery, credit-card fraud, prostitution and eventually murder. First, a drug-dealer, a bit-part actor and a musician were killed on his orders; and then, when some of his ‘Family’ were arrested on other charges, he announced Helter Skelter day.

That night, August 8th 1969, four of his demented disciples invaded the house of director Roman Polanski and murdered five people, including his pregnant wife Sharon Tate. Before they left, they used Tate’s blood to daub the word PIG on the front door.

When he later heard the names of the victims, Manson – who’d chosen the house only because one of the people on his death-list had once lived there – was delighted. As Hollywood panicked, he led the next murderous raid himself, selecting a house for no other reason than that it was next-door to someone he disliked. This time a forty-four-year old supermarket president called Leno LaBianca and his wife Rosemary were stabbed in a frenzy, and their blood used to write DEATH TO PIGS, RISE and HEALTER (sic) SKELTER on the walls. The word WAR was carved onto Mr LaBianca’s stomach.