100 Most Infamous Criminals (22 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

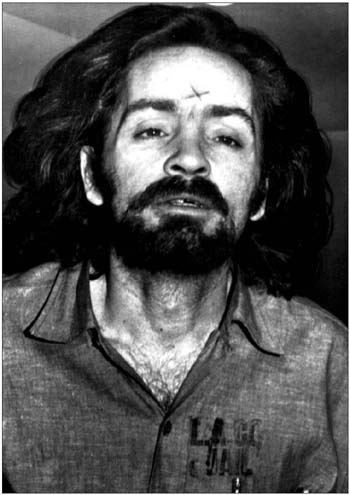

Charles Manson became one of the most hated figures in America

The two cases of multiple murder were investigated by different law-enforcement agencies and at first no connections were made. Manson and members of the ‘Family’ were arrested, but on other charges, and were eventually released. But then one of Manson’s female acolytes confessed to a cellmate that she’d been involved in the murders and eventually he and other members of the ‘Family,’ two of whom later turned state’s evidence, were picked up.

The trial of Manson and three of his female acolytes – others were tried elsewhere – lasted nine months, and was not without sensation. When Manson appeared in the dock one day with a cross carved with a razor-blade onto his forehead, the three girls soon burned the same mark onto theirs. On another occasion 5-foot 2-inches tall Manson jumped 10 feet across the counsel table to attack the judge, who afterwards took to carrying a revolver.

In the end all four were sentenced to death, but were spared execution when the California Supreme Court voted to abolish the death penalty in 1972. When last heard of, Manson was working as a chapel caretaker in Vacaville Prison in southern California. He has been denied parole eleven times to date, and will next be eligible to apply in 2012.

Manson has been denied parole a total of eleven times

Members of Manson’s ‘Family’ – all were spared the death penalty

Walter Leroy Moody

W

alter Leroy (Roy) Moody Jr. was a bomb-maker: an intelligent, manipulative man with a sense of failure and a strong grudge against the world. The trouble was, he was also a perfectionist, with a perfectionist’s distaste for the ordinary. His bombs were carefully designed – at some danger to himself – to do as much damage as possible, and once he’d hit on the best way of ensuring this, he saw no reason to change it at all. Unfortunately for him, then, every calling card he sent out in his campaign for revenge had a signature – a signature the police had already seen.

Moody’s first calling card arrived on the afternoon of December 16th 1989 at a house near Birmingham, Alabama, when Robert Vance, a US Circuit Court of Appeals judge, sitting with his wife at the kitchen table, opened a package. An explosion ripped into him and killed him. His wife, sitting at the opposite end of the table, was hurled back onto the floor and hit by a nail, added as shrapnel, which tore through her liver and one of her lungs.

US marshals across the country were immediately warned of a possible continuing parcel-bomb attack on people in the judiciary. Extreme care, they were told, was to be taken with any suspicious packages. Two days later, sure enough, another bomb was found, this time by a security officer using an X-ray machine to vet mail at the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, where Judge Vance had served.

That was not the only one of Moody’s calling cards, though, that was delivered that day. For that afternoon, in Savannah, Georgia when black attorney Robert Robinson opened his mail at his desk, another explosion ripped through him, blowing off his arm and leaving pieces of his bone and flesh painted on the walls. The same would have happened, no doubt, to the NAACP branc-hpresident in Jacksonville, Mississippi, if she hadn’t had trouble with her car. By the time she got into her office the following day, she’d heard the word about the other package-bombs and, just to be safe, called in the sheriff’s office.

Robinson had by that time died in hospital. But the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms had already, with the help of the Atlanta police, dismantled the bomb sent to the 11th Circuit Court. Using this bomb as a template, they were now able relatively easily to take apart the Jacksonville one. Both were pipe bombs, but they had curious features: nails had been attached to the pipe by rubber bands, and the ends of the pipes had been closed off with welded metal plates. A bolted rod had also been passed through the pipe to strengthen it. None of the veteran bomb-experts had seen a configuration like this before.

The first assumption of detectives was the bombs were part of a campaign by a white supremacist group. For a tear-gas grenade had exploded in a package at an NAACP office in Atlanta the previous August, and at around the same time a letter titled ‘Declaration of War’ had begun showing up at television stations, including one in Atlanta, railing against the 11th Circuit Court of Appeal – which, among other things, tried civil rights cases – and threatening poison-gas attacks. Another letter had been received by an Atlanta TV anchorwoman, denouncing and threatening with death US judges and black leaders for failing ‘to prevent black men from raping white women.’

When no supremacist group claimed responsibility, though, the FBI began to change its mind – to believe that the bombings had been the work of a white middle-aged loner with a grudge. And this was when local bomb-squad veterans began to remember that they’d seen a bomb constructed like this before.

In 1972 a woman called Hazel Moody had opened a package she thought to contain model-airplane parts for her husband. It exploded in her face, leaving her with first-and second-degree burns, a destroyed hand and a badly damaged eye. But the package had actually been addressed to a car dealership which had recently repossessed her and her husband’s car. It was meant to be posted. Her husband, Roy Moody, had been responsible, had been jailed for five years, but was still, apparently, appealing his sentence, most recently – and unsuccessfully – in the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Moody fitted the profile of a middle-aged white loner with a grudge exactly. By now in his mid-fifties, he’d trained in both neurosurgery and the law, but he’d failed at the first and couldn’t practise the second because of the bomb conviction. He was manipulative and potentially dangerous – a 1983 trial of Moody for attempted murder had ended in a hung jury. He was soon arrested.

The trouble was that the FBI still had nothing but strong circumstantial evidence against him. It wasn’t until his second wife, whom he’d brutalized, agreed to testify that the murder case could finally be made. She told the court in detail about the locked bedroom she was never allowed to enter; about how she was sent off in disguise to distant stores to make purchases of bomb-ingredients for him; and how she mailed packages for him, packages she wasn’t allowed to look at. On the testimony of his battered wife, Roy Moody, already serving life without parole on federal charges relating to the bombings, was finally sentenced to the electric chair in Alabama for the murder of Judge Vance in 1997.

Herman Mudgett, aka H.H. Holmes

H

erman Mudgett, alias H.H. Holmes, alias H.M. Howard, was an insurance swindler and a bigamist. But he was also one of the most prolific serial killers in American history. He liked to handle dead bodies.

He was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire in May 1860 and certainly trained as a doctor, perhaps in New York. But he first came to fame in Chicago where, after deserting his wife and using the name H.H. Holmes, he took over a pharmacy from its proprietor, a Mrs. Holden, who’d been employing him until she disappeared. Business soon thrived and in 1890, having married again, he started building a battle-mented house-cum-hotel which became known as Holmes’s Castle.

Holmes’s Castle was no ordinary establishment, though. For concealed within it was a maze of shafts and chutes and hidden passages. There were also secret airtight rooms which could be filled with piped gas via a control-switch in the office, and a basement which contained huge vats. Only Mudgett himself knew the Castle’s overall design, for he hired different builders to work, in isolation from each other, on their own small sections of the building.

It was completed and opened in time for the Chicago Exposition of 1893, which brought huge numbers of visitors to the city, many of them young women on their own. Having already, allegedly, got rid of several of his mistresses, Mudgett now had a machine that could deliver his female victims to death with maximum efficiency. After luring them from their rooms and attempting to seduce them, he would place them in one of the shafts giving onto a secret cell, and there gas them to death behind airtight glass panels. Then a chute would deliver their bodies to the basement, where he could dissect them at will, before tossing what remained of them into vats containing acid and lime.

In the year of the Exposition, Mudgett killed tens, perhaps hundreds, of young women and girls. But finally he got greedy. For among his victims were two rich sisters from Texas and he decided, rather than stay in Chicago, to go after their fortune. So he set fire to the Castle, and claimed the insurance; then, when the insurance company refused to pay and the police announced an investigation into the causes of the fire, he fled the city southward.

Once in Texas he ingratiated himself with the two sisters’ relatives, and did his best to swindle them out of a $60,000 legacy. When this failed – and with the law close behind him – he took off on a stolen horse. He was finally caught in Missouri, using the name H.M. Howard, and already charged there with fraud. But with the help of a crooked lawyer he was granted bail – and again he escaped.

He next appeared in Philadelphia, where a man called Benjamin Pitezel had been his associate, it later emerged, in a number of insurance scams. Pitezel, whose life had been insured for $10,000, was soon blown up in what seemed to be an accident; Mudgett was one of those who identified his body. He had, of course, killed Pitezel himself and when the insurance company paid the $10,000 to Pitezel’s wife, he disappeared with her and her three children. The children didn’t last long, though: they were later found dead, two of them in a basement in Toronto, Canada, and one in a chimney in Irvington.

Mudgett was finally arrested, along with his mistress, in Boston in mid-1885. He’d been tracked down by detectives who were after him not, oddly, for the crimes he’d committed in Chicago or Philadelphia, but for jumping bail in Missouri and horse-stealing in Texas – at that time a capital offence. The Philadelphia courts, however, had first crack at him, for the murder of Benjamin Pitezel, to which he’d readily confessed. Evidence in the trial, though, was also given by a Chicago mechanic, who told how he’d been hired by Mudgett to strip the flesh off three corpses at his Castle. It was only after this that the Chicago police began seriously to investigate that long-ago fire and found the secrets Holmes’s Castle had contained

Herman Mudgett was hanged at Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison on May 7th 1896. In 2003, 107 years later, the Hollywood trade papers announced that two separate films about his criminal career were to be made.

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow

T

he relationship between Bonnie Parker and farmer’s boy Clyde Barrow didn’t get off to a good start. The first time twenty-one-year-old Clyde came calling at her house in Cement City, Texas, he was arrested for burglary and car theft – he later got two years in jail. Nineteen-year-old Bonnie, though, was no stranger to this kind of trouble – the man she’d married three years before had been sent down for ninety-nine years for murder. So she knew just what to do. She smuggled a gun into Clyde as he languished behind bars, and he duly made his escape. Trouble was, he was recaptured in a matter of days after holding up a railroad office. This time he got fourteen years.

True love, though – as it’s said – conquers all and Clyde was soon out, though this time on crutches: he’d persuaded a fellow prisoner to cut off two of his toes with an axe. To please Bonnie’s devout Baptist mother, he then tried to go straight. He took a job in Massachusetts, but it didn’t last long – he pined too much for home. He returned to West Dallas, and three days later they were both gone, off to gather material for the poem Bonnie later wrote,

The Story of Bonnie and Clyde

.

With three men along for the ride, Bonnie and Clyde robbed and hijacked their way across Texas. Bonnie was picked up on suspicion of car theft, so the first three murders the gang was responsible for were committed without her. First, in April 1932, they shot a jeweller in Hillsboro, Texas for just $40, and then, just for kicks, a sheriff and his deputy as they stood minding their business outside a dance-hall.