13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown (21 page)

Read 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown Online

Authors: Simon Johnson

And, of course, there was the money. The vast amounts of money flowing through Wall Street and the extreme free market ethos of the industry resulted in ever-larger amounts of money spinning off into the bank accounts of top traders, salesmen, and bankers. From 1948 until 1979, average compensation in the banking sector was essentially the same as in the private sector overall; then it shot upward, as shown in

Figure 4-1

, until in 2007 the average bank employee earned twice as much as the average private sector worker.

76

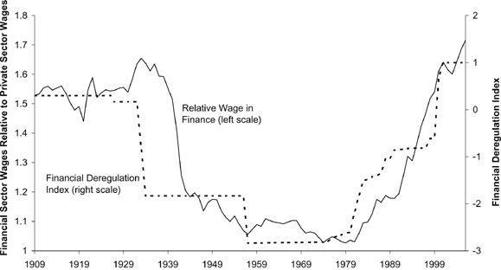

Even after taking high levels of education into account, finance still paid more than other professions. Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef have analyzed financial sector compensation and found that the “excess relative wage” in finance—the amount that cannot be explained by differences in education level and job security—grew from zero around 1980 to over 40 percentage points earlier this decade; 30–50 percent of excess wages in finance cannot be explained by differences in individual ability. They also found that deregulation was one factor behind the recent growth of compensation in finance. (

Figure 4-2

shows the relationship between the unadjusted relative wage in the financial sector—the ratio between average wages in finance and average wages in the private sector as a whole—and the extent of financial deregulation, as calculated by Philippon and Reshef.)

77

Figure 4-2: Relative Financial Wages and Financial Deregulation

Source: Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef, “Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Financial Industry: 1909–2006,” Figure 6.

The rewards for success grew much, much faster as traders’ potential bonuses climbed into the millions and then the tens of millions. In 2008—which was a horribly bad year for most banks—1,626 JPMorgan Chase employees received bonuses of more than $1 million; at the smaller Goldman Sachs, which had thirty thousand employees, 953 received bonuses of more than $1 million, and 212 received bonuses of more than $3 million.

78

In the 1990s, Internet start-ups were seen as the quickest route to vast wealth, for the lucky few who founded companies that successfully went public. By the 2000s, it was investment banks and hedge funds, where smart college graduates could

expect

to make millions.

Wall Street began to skim off the cream of America’s top schools—not only graduates of business schools and Ph.D. programs in math and science, but twenty-two-year-old college students with no background or expertise in anything at all. As investment banks began descending onto Ivy League campuses and tempting students with stories of client “impact,” dinners at expensive restaurants, and glimpses of much greater wealth, seniors who had never even wondered what a bond was suddenly wanted to be investment bankers. Sealing the deal was the fact that Wall Street was perceived as the ultimate door-opener, a respectable way to make money and then, like Robert Rubin, go into public service. The point of the “Greed is good” speech was that by pursuing profits (both for your company and for yourself) you were contributing to the greater good. For college seniors, it was easy to think that maximizing their personal earnings coincided with maximizing societal good—making it easy to justify joining the ranks of the bankers on Wall Street.

As a result, banking and finance became more and more popular among the young and the privileged. Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz have examined data on Harvard undergraduates and found that while only 5 percent of men in classes around 1970 were in finance fifteen years after graduation, that figure tripled to 15 percent for classes around 1990.

79

The share of each class entering banking and finance careers grew from under 4 percent in the 1960s to 23 percent in recent years.

80

At Princeton’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, “Operations Research and Financial Engineering” became the most popular undergraduate major.

81

The banks thus became major beneficiaries of the American educational system. Whether society benefited is another question. Kevin Murphy, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny have argued that society benefits more when talented people become entrepreneurs who start companies and create real innovations than when they go into rent-seeking activities that redistribute rather than increase wealth.

82

If this is true, then this diversion of talent to Wall Street constituted a real tax on economic growth over the last two decades.

Among the economic and intellectual elites, finance became a highly prestigious and desirable profession. Working on Wall Street became a widely acknowledged marker for educational pedigree, intelligence, ambition, and wealth. Outsiders may not have understood exactly what happened on a trading floor or in a hedge fund, but they knew that it was important, it was fast-moving, it was intellectually complicated, it had something to do with greasing the wheels of the global economy, and it had something to do with making it easier for ordinary people to buy houses. They also knew that it was very well paid. In America, where we like to believe that wealth is a function of hard work and contribution to society, that was all good.

THE WALL STREET–TREASURY COMPLEX

This combination of money, people, and prestige created what Jagdish Bhagwati identified in 1998 as the “Wall Street–Treasury complex.”

83

Bhagwati described how the ideology of free markets “lulled many economists and policymakers into complacency about the pitfalls that certain markets inherently pose,” while the revolving door placed representatives of Wall Street into influential positions in Washington. “This powerful network,” he wrote, “is unable to look much beyond the interest of Wall Street, which it equates with the good of the world.” Bhagwati was writing in the context of global financial liberalization, which the United States was then pushing on developing countries (both directly and through its influence at the IMF), and which had contributed to the emerging market crises of the past year.

By the time of Bhagwati’s article, the power of Wall Street reached deep into Washington. The major banks, including both traditional investment banks and commercial banks that expanded into securities and derivatives, had spent the last two decades opening and exploiting vast new mines filled with money. They had funneled millions of dollars of that money to key congressmen who could make or break legislation affecting the financial sector. The treasury secretary was a former chairman of Goldman Sachs, the assistant secretary for financial markets was a former Goldman partner, and the Federal Reserve chairman was an ardent fan of Wall Street. The Clinton administration, which had tied its fortunes to keeping Wall Street bond traders happy, was deep into a multiyear campaign to boost homeownership rates and was depending on the financial sector to make it possible.

Behind these Washington power brokers was a new conventional wisdom about the importance and value of Wall Street. The previous Nobel Prize in economics had been given to two economists who had helped launch the derivatives revolution and were now partners at the hottest hedge fund in the world. The dogma of financial innovation had few doubters in Washington. Vibrant, profitable banks were assuming the status of national champions in a country that saw the transition from manufacturing to knowledge-intensive services as its destiny. And Wall Street was the most prestigious destination for graduates of America’s top universities. For all intents and purposes, Wall Street had taken over.

*

A put option gives its holder the right to sell an asset, such as a share of stock, at a predetermined price. If the stock falls sharply in value, the put option allows the holder to sell it at a higher-than-market price, and is therefore a form of protection against risk. The “Greenspan put” was thought to be the equivalent of a put option for everyone in the market.

*

Owning a house has other advantages, such as increased freedom in deciding what to do with the house and land and increased peace of mind. However, these advantages have nothing to do with the value of the house as an investment.

5

THE BEST DEAL EVER

These amendments are intended to reduce regulatory costs for broker-dealers by allowing very highly capitalized firms that have developed robust internal risk management practices to use those risk management practices, such as mathematical risk measurement models, for regulatory purposes.

—Securities and Exchange Commission, “Final Rule: Alternative Net Capital Requirements for Broker-Dealers That Are Part of Consolidated Supervised Entities,” Effective August 20, 2004

1

By the mid-1990s, Wall Street was a dominant force in Washington. It had survived the implosion of the savings and loan industry in the late 1980s, the election of a Democratic president in 1992, a congressional investigation of predatory subprime lending in 1993, and a wave of scandals caused by toxic derivatives deals in 1994 without facing any significant new constraints on its ability to make money.

The U.S. financial elite did not owe its rise to bribes and kickbacks or blood ties to important politicians—the usual sources of power in emerging markets plagued by “crony capitalism.” But just as in many emerging markets, it constituted an oligarchy—a group that gained political power because of its economic power. With Washington firmly in its camp, the new financial oligarchy did what oligarchies do—it cashed in its political power for higher and higher profits. Instead of cashing in via preferred access to government funding or contracts, however, the major banks engineered a regulatory climate that allowed them to embark on an orgy of product innovation and risk-taking that would create the largest bubble in modern economic history and generate record-shattering profits for Wall Street.

When the entire system came crashing down in 2007 and 2008, governments around the world were forced to come to its rescue, because their economic fortunes were held hostage by the financial system. The title of Louis Brandeis’s 1914 book,

Other People’s Money,

referred to ordinary people’s bank deposits, which could be used by investment bankers—“Our Financial Oligarchy”—to control industries and generate profits. In 2008, however, the banks found another way to tap other people’s money: the taxpayer-funded bailout.

THE GOLDEN GOOSE

The boom in real estate and finance in the 2000s resulted from the explosive combination of a handful of financial “innovations” that were invented or greatly expanded in the 1990s: structured finance, credit default swaps, and subprime lending. Most financial regulators looked on the creation of this new money machine with benevolent indifference. Structured financial products were sold largely to “sophisticated” investors such as hedge funds and university endowments and therefore subject to limited oversight by the Securities and Exchange Commission; credit default swaps were insulated by regulatory inattention and then by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act; subprime lending was winked at by the Federal Reserve. That was how the financial sector wanted it, and Washington was happy to oblige.

Traditionally, investors invested in financial assets that had some direct tie to the real economy: stocks, corporate or government bonds, currencies, gold, and so on. By contrast, banks engineer structured products to have any set of properties (maturity, yield, risk, and so forth) that they want.

2

Structured products include pure derivatives, discussed in

chapter 3

, which are side bets on other financial assets. For example, an investor can pay $100 to a bank and get back, one year later, an amount that is calculated based on the performance of several currencies and interest rates. They can also be built by buying actual financial assets (mortgages, student loans, credit card receivables, and so on), combining them, and taking them apart in various ways to create new “asset-backed” securities. Or they can combine real assets with derivatives in increasingly complicated mixes.

Structured finance, in principle, serves two main purposes. First, it creates new assets that people can invest in. Instead of being limited to publicly traded stocks and bonds, investors can choose from a much broader menu of assets, each with unique characteristics to attract a particular investor; for example, securities can be manufactured to help investors match the timing of their assets and their liabilities.

*

Second, by creating assets that are more attractive to investors, structured finance should make it easier for businesses to raise money. While investors might demand a high rate of interest to invest in an airline route from Los Angeles to Shanghai, they might accept a lower rate if that route were packaged with an option to buy oil at a cheap price in the future. (If oil prices rise, hurting demand for long-distance flights, the option will increase in value.) Lower rates make it easier for businesses to raise money.