13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown (23 page)

Read 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown Online

Authors: Simon Johnson

As the business boomed, the large banks dived in, snapping up subprime lenders. Among the top twenty-five subprime lenders, First Franklin was bought by National City and later by Merrill Lynch; Long Beach Mortgage was bought by Washington Mutual; Household Finance was bought by HSBC; BNC Mortgage was bought by Lehman Brothers; Advanta was bought by JPMorgan Chase; Associates First Capital was bought by Citigroup; Encore Credit was bought by Bear Stearns; and American General Finance was bought by AIG.

17

Not only did buyers want the lucrative fees available from originating subprime loans, but many of them wanted a captive source of loans for their mortgage securitization machines. Large banks also expanded their subprime operations by working with independent mortgage lenders and brokers. According to the head of Quick Loan Funding, a subprime lender, Citigroup provided the money for loans to borrowers with credit scores below 450 (at the time, the national median was about 720).

18

JPMorgan Chase aggressively marketed its “no doc” and “stated-income” programs to mortgage brokers and used slogans such as “It’s like money falling from the sky!”

19

If subprime lending was pioneered far from Wall Street, by the 2000s Wall Street couldn’t get enough of it.

Housing was not the only bubble made possible by cheap money, aggressive risk-taking, and structured finance. The 2000s saw a parallel bubble in the commercial real estate market, where banks were willing to finance purchases at ever-increasing valuations, in part because they were able to use commercial mortgage-backed securities to unload the large, risky loans they were making. There was also an enormous boom in takeovers of companies by private equity firms, again made possible by cheap loans advanced by banks and then syndicated to groups of investors or used as raw material for new structured products. These bubbles overlapped in takeovers of real estate investment trusts (REITs), companies that invest in real estate. In February 2007, the Blackstone Group bought Equity Office Properties Trust for $39 billion in the largest leveraged buyout ever; Blackstone immediately flipped most of Equity Office’s buildings to other buyers (who borrowed as much as 90 percent of the purchase price), many of whom took significant losses as the real estate market crashed.

20

In October 2007, Tishman Speyer spent $22 billion to buy Archstone-Smith Trust, much of it financed by a group of banks led by Lehman Brothers; losses on that deal would be one factor that helped lead to the downfall of Lehman less than a year later.

21

FORCE-MOLTING

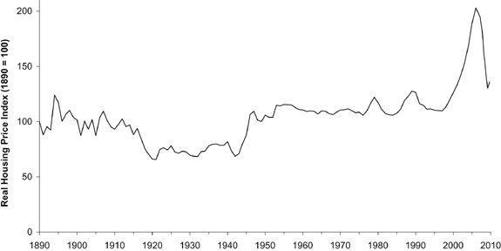

But the emblematic bubble of the decade, and the one whose implosion led directly to the financial crisis, was the housing bubble, in which prices soared to almost twice their long-term average (see

Figure 5-1

).

22

The increased availability of mortgage loans, with lower initial monthly payments, increased homebuyers’ ability to pay, pushing prices upward. Continually rising housing prices seemed to eliminate the risk of default, since borrowers could always refinance when their mortgages became unaffordable, making mortgage-backed securities and CDOs more attractive to investors and to the investment banks that manufactured them. Higher prices also induced existing homeowners to take out home equity loans, providing more raw material for asset-backed securities and CDOs. Lower risk lowered the price of credit default swaps on mortgage-backed debt, making CDOs and synthetic CDOs easier to create. Increased Wall Street demand for mortgages (to feed the securitization pipeline) funneled cheap money to mortgage lenders, who sent their sales forces out onto the streets in search of more borrowers; by the early 2000s, many prime borrowers had already refinanced to take advantage of low rates, and so subprime lending became a larger and larger share of the market. And the cycle continued.

Figure 5-1: Real U.S. Housing Prices, 1890–2009

Source: Robert Shiller, Historical Housing Market Series. Used by permission of Mr. Shiller. Data were originally used in Robert Shiller,

Irrational Exuberance

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Ordinarily, the instinct for financial self-preservation should prevent lenders from making too many risky loans. The magic of securitization relieved lenders of this risk, however, leaving them free to originate as many new mortgages as they could. Because mortgages were divided up among a large array of investors, neither the mortgage lender nor the investment bank managing the securitization retained the risk of default. That risk was transferred to investors, many of whom lacked the information and the analytical skills necessary to understand what they were buying. And the investors assumed that they didn’t need to worry about what they were buying, because it was blessed by the credit rating agencies’ AAA rating.

Ironically, even though securitization theoretically allowed banks to pass on all the default risk to their clients, some kept some of the risk anyway. Either they really believed that the senior tranches of their CDOs were risk-free, or there was more demand for the riskier junior tranches and they couldn’t find enough buyers for the senior tranches. Here again, they depended on financial innovation in the form of structured investment vehicles (SIVs)—special-purpose entities that raise money by issuing commercial paper and invest it in longer-term, higher-yielding assets. Citigroup, for example, used SIVs to buy over $80 billion in assets by July 2007.

23

These vehicles allowed banks to invest in their own structured securities without having to hold capital against them; since SIVs were technically not part of the bank in question—even though they were wholly owned by that bank, which might even have promised to bail them out if necessary

24

—their assets were not counted when determining capital requirements. The result was that SIVs enabled banks to take on more risks with the same amount of capital.

SIVs were a Wall Street variation on one form of crony capitalism. In an emerging market, when a major family-owned conglomerate sets up a new company, it can legally walk away should things go bad. Because the new company has the family name behind it, however, the family will come under pressure to prop it up in a crisis.

25

And just as in emerging markets, when things did go bad in 2007 and 2008, many banks, including Citigroup, bailed out their SIVs, incurring billions of dollars of losses in the process. But as long as housing prices were soaring, SIVs were another way to make more profits using less capital. In addition, by soaking up the senior tranches of CDOs, they helped keep the securitization machine going at full volume.

Rising housing prices created their own momentum, as bubbles do. As people saw their friends and neighbors cashing in on the housing boom, they rushed to get in on the action. The environment became so filled with stories about people making money in housing that even skeptics decided that everyone else couldn’t be wrong, creating what Robert Shiller has called a “rational bubble.”

26

Even investors who knew the boom could not last were betting that they could buy high and sell higher before the music stopped.

On a factory farm, when hens start laying fewer eggs, they are “force-molted”—“starved of food and water and light for several days in order to stimulate a final bout of egg laying before their life’s work is done.”

27

After 2004, when many qualified borrowers had already refinanced and houses were so expensive they could only be bought with exotic mortgages, the real estate and finance industries launched an all-out effort to get people into new houses and squeeze out a few last years of golden eggs. In the peak years, the bubble was sustained by brand-new mortgage products that only existed because they provided raw material for CDOs. At the height of the boom, over half of the mortgages made by Lennar, a national housing developer, were interest-only mortgages or optional-payment mortgages whose principal went

up

each month; in 2006, almost one in three had a piggyback second mortgage.

28

Between 1998 and 2005, the number of subprime loans tripled, and the number that were securitized (as measured by First American LoanPerformance) increased by 600 percent.

29

In 2005, a consortium of Wall Street banks created standard contracts for credit derivatives based on subprime mortgages, making it even easier to create synthetic subprime CDOs.

30

These developments all confirmed the predictions of economist Hyman Minsky, who had warned that “speculative finance” would eventually turn into “Ponzi finance.”

31

The end result was a gigantic housing bubble propped up by a mountain of debt—debt that could not be repaid if housing prices started to fall, since many borrowers could not make their payments out of their ordinary income. Before the crisis hit, however, the mortgage lenders and Wall Street banks fed off a giant moneymaking machine in which mortgages were originated by mortgage brokers and passed along an assembly line through lenders, investment banks, and CDOs to investors, with each intermediate entity taking out fees along the way and no one thinking he bore any of the risk.

32

GREENSPAN TRIUMPHANT

An emerging market oligarchy uses its political power and connections to make money through such means as buying national assets at below-market prices, getting cheap loans from state-controlled banks, or selling products to the government at inflated prices. In the United States, the banking oligarchy (and its allies in the real estate industry) used its political power to protect its golden goose from interference and to clear away any remaining obstacles to its growth. The banks’ objectives included both the elimination or nonenforcement of existing regulations and the prevention of new regulations that might stifle profitable innovations. Their sweeping success enabled them to take on more and more risk, increasing their profits but also increasing the potential cost of an eventual crash.

At the top of the major commercial banks’ wish list was the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, which was finally achieved in 1999. By that point, the separation of commercial and investment banking had been severely weakened by a series of Federal Reserve actions that allowed commercial banks, through their subsidiaries, to underwrite many types of securities; in addition, the new business of derivatives fell outside Glass-Steagall altogether, and commercial banks such as Bankers Trust and J.P. Morgan were among the pioneers in that market.

In 1996, the Fed struck a major blow for deregulation, allowing bank subsidiaries to earn up to 25 percent of their revenues from securities operations, up from 10 percent.

33

That same year, the Fed overhauled its regulations to make it easier for banks to gain approval to expand into new activities. Congress also changed the rules for banks seeking to expand into new businesses, relieving banks of the need to obtain approval from the Federal Reserve and putting the onus on the Fed to actively disapprove of any new activities.

34

As long as Glass-Steagall remained on the books, however, the 25 percent revenue limit posed a barrier, and there was still the risk that Congress or the courts might overrule a friendly decision by the Fed.

When Travelers and Citicorp merged in 1998—bringing together a major commercial bank and a major insurance company that owned a major investment bank—Glass-Steagall required the new Citigroup to break itself up within two years. Citigroup’s only recourse was to get the law repealed. Congress obliged in 1999 with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which created a new category of financial holding companies that are authorized to engage in any activities that are financial in nature, incidental to a financial activity, or complementary to a financial activity—including banking, insurance, and securities.

35

With this legislation, Donald Regan’s dream of a true financial supermarket that could offer all financial services was not only legal, it seemed to be embodied in the new Citigroup.

The passage of Gramm-Leach-Bliley freed not only Citigroup but also Bank of America, J.P. Morgan, Chase, First Union, Wells Fargo, and the other commercial megabanks created by the ongoing merger wave to plunge headlong into the business of buying, securitizing, selling, and trading mortgages and mortgage-backed securities. Because there was no way to seal off the banks’ securities operations from their ordinary banking operations, this meant that the government guarantee of the banking system, in place since the 1930s, was effectively extended to investment banking. Deposits that were insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation could be invested in risky assets, with the assurance that losses would be made up by the FDIC. The larger the bank, the stronger its government guarantee. In 1984, when Continental Illinois was bailed out, the comptroller of the currency said that the top eleven banks were too big to fail; by 2001, there were twenty banks that were as big relative to the economy as the eleventh-largest bank had been in 1984.

36

As in any capitalist system, bank employees and shareholders would enjoy the profits from their increasingly risky activities; but now the federal government was on the hook for potential losses.