13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown (30 page)

Read 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown Online

Authors: Simon Johnson

But on another level, the stress tests worked. For months, leading government figures had repeatedly assured the public that the banking system was secure. On April 21, Geithner testified, “Currently, the vast majority of banks have more capital than they need to be considered well capitalized by their regulators.”

41

The stress tests were a way of committing the government to back those words with money. Once the government had certified the banks’ balance sheets, and once the banks had raised the capital the government demanded, the government would have no excuse not to bail them out if needed. This was not entirely a good thing: once the pressure to get their houses in order was off, the banks were in no rush to unload their toxic assets.

The strengthened government guarantee was one ingredient pulling the megabanks back from the abyss. Another was reduced competition. Not only did Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Washington Mutual, and Wachovia all vanish, but an entire class of nonbank mortgage lenders evaporated with the housing bubble. With fewer competitors, the survivors could sweep up larger shares of the market and demand higher margins and fees. And a third factor was the cheap money being pumped into the economy by the Federal Reserve. Banks’ primary raw material is money. Less competition and cheap money meant higher revenues and lower costs at the same time.

With low interest rates, banks could raise money from depositors virtually for free; they could borrow cheaply from each other; they could borrow cheaply at the Fed’s discount window; they could sell bonds at low interest rates because of FDIC debt guarantees; they could swap their asset-backed securities for cash with the Fed; they could sell their mortgages to Fannie and Freddie, which could in turn sell debt to the Fed; and on and on. Because so much cash was easily available to the banks, they could not suddenly run out of money. And because short-term interest rates fell further than long-term interest rates, the basic business of banking—borrowing short and lending long—became more profitable. The indefinite government lifeline gave the banks time to recapitalize themselves with profits from current operations.

Effectively, the government’s strategy was to bail the banks out of their problems by helping them make large profits, juiced by reduced competition and cheap money, to plug the ever-widening hole created by their toxic assets. As part of its stress tests, the Federal Reserve concluded that the four largest banks—Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo—stood to lose another $425 billion on existing assets through the end of 2010, but would fill more than half of that hole with $256 billion in profits over the same period.

42

For the stronger banks, such as JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs, the result was a quick return to profitability and the appearance of health; the weaker ones, such as Citigroup and Bank of America, gained time to wait for an economic recovery to bail them out of their bad loans.

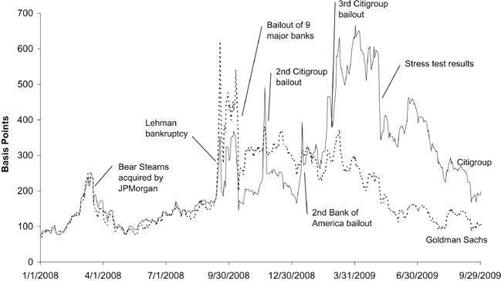

Figure 6-1: Credit Default Swap Spreads, 5-Year Senior Debt

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP

Repeated public assurances, the stress test results, and the earlier emergency bailouts of Citigroup and Bank of America made it clear not only that the government would not let a major bank fail, but that the government would bail out banks in their existing form, with their existing management, and without imposing haircuts on bank creditors.

Figure 6-1

shows the perceived likelihood that major banks would go bankrupt, as measured by the price of credit default swap protection on their debt; each time the government intervened, the market’s fears ebbed, until finally the stress tests broke the year-long fever. That was what Wall Street needed to hear: they could go back to doing business as usual, and Washington would be there if things went wrong. A panic that began with an attempt to reduce moral hazard by letting Lehman fail only ended when everyone was convinced that the government would not let another major bank fail—magnifying moral hazard to an unprecedented degree. And as the real economy began to bottom out over the summer, it became easier and easier to make money again. But this was only true for the major banks; in the real economy, it became harder and harder to get a loan. According to the Federal Reserve’s survey of bank loan officers, every type of loan became harder to get in every quarter of 2008 and through the first three quarters of 2009.

43

In short, Paulson, Bernanke, Geithner, and Summers chose the blank check option, over and over again. They did the opposite of what the United States had pressed upon emerging market governments in the 1990s. They did not take harsh measures to shut down or clean up sick banks. They did not cut major financial institutions off from the public dole. They did not touch the channels of political influence that the banks had used so adeptly to secure decades of deregulatory policies. They did not force out a single CEO of a major commercial or investment bank, despite the fact that most of them were deeply implicated in the misjudgments that nearly brought them to catastrophe. Summers was aware of the irony, although he disagreed that the situations were exactly parallel. “I don’t think I would quite accept the characterisation that we’re in the position that the Russians were in in 1998,” he said in a 2009 interview, because the United States did not face the problem of foreign capital flight. But, to his credit, he acknowledged,

There have been moments, certainly, when I understood better some of the reactions of officials in crisis countries now than one was able to from the outside at the time. It is easier to be for more radical solutions when one lives thousands of miles away than when it is one’s own country.

44

The total cost of all those blank checks is virtually incalculable, spread across the more or less direct subsidy programs (preferred stock purchases, asset guarantees, and so on) and the emergency liquidity and insurance programs to unfreeze the markets for commercial paper, asset-backed securities, or bank debt. It is incalculable because the different types of support—lending commitments, asset guarantees, preferred stock purchases, and such—cannot simply be added up. At the upper end of the relevant ballpark, the special inspector general for TARP estimated a total potential support package of $23.7 trillion, or over 150 percent of U.S. GDP.

45

This represents the theoretical potential liabilities of the government; the net cost will be far lower, since not all lending commitments will be used up, most loans will be paid back, most preferred shares will be bought back, most of the assets the government has guaranteed will not become worthless, and so on.

In the end, the government’s strategy succeeded in bringing the financial system back from the brink of ruin, although not in restoring that system to health and stimulating lending to the real economy. There are three crucial steps in responding to a financial crisis: ending the panic, preventing economic activity from collapsing, and laying the groundwork for a sustainable recovery. The government largely succeeded in the first step, and the stimulus package passed in early 2009 helped with the second step. But the unconditional support provided to the financial system only exacerbated the weaknesses and incentives that had created the crisis in the first place.

Despite the tremendous cost of bailing out the financial system, the cost of letting the system collapse would probably have been even higher. But was bailing out Wall Street the only way to avoid disaster?

The beginning of 2009 saw a raging public debate between the blank check option and the takeover option. The key question was not whether to intervene; virtually everyone involved acknowledged that the megabanks were too big to fail, because if any one of them collapsed the system as a whole might collapse. The question was what to do about it. The government argued that the banks’ fundamental situation was not that bad—banks faced a “liquidity crisis” caused by short-term fear, not a “solvency crisis” caused by severe economic losses—and that the best way to contain that fear was to keep the banks going in their current form; anything more drastic would only cause panic.

The opposing view, put forward by many people including Nobel Prize laureates Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz (and non–Nobel laureates like us), was that some major banks were deeply sick and that successive bailouts amounted to vast giveaways of taxpayer money that would do little to solve either the short-term or the long-term problems in the financial sector. As Krugman said, “Every plan we’ve heard from Treasury amounts to the same thing—an attempt to socialize the losses while privatizing the gains.”

46

But because the government only had enough money to keep the banks afloat, it was not actually restoring them to the health necessary for them to start lending again. The problem was both political and economic. In Krugman’s words:

As long as capital injections are seen as a way to bail out the people who got us into this mess (which they are as long as the banks haven’t been put into receivership), the political system won’t, repeat, won’t be willing to come up with enough money to make the system healthy again. At most we’ll get a slow intravenous drip that’s enough to keep the banks shambling along.

47

By leaving the banks in the hands of their existing managers and going out of its way to minimize its own influence, the government was ensuring that it had no way to encourage banks to do anything other than hoard their cash, and no way to affect bank behavior in the future. Attempts by the Federal Reserve to stimulate the economy were absorbed by what Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, called “the Blob” of large, sick banks. “Those banks with the greatest toxic asset losses were the quickest to freeze or reduce their lending activity,” Fisher said; in addition, “the dead weight of [the megabanks’] toxic assets diminished the capacity of markets to keep debt and equity capital flowing to businesses and scared investors away.”

48

Although bank bailouts did prevent economic calamity, they would do little to ensure financial stability or economic prosperity.

Krugman, Stiglitz, and others argued that the government should take over banks, clean them up so they would function normally, and sell them back into private hands when possible, as in an FDIC intervention. In a February 2009 interview, Stiglitz said, “Nationalization is the only answer. These banks are effectively bankrupt.”

49

Other prominent supporters of a government takeover included economics professors Nouriel Roubini and Matthew Richardson and Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

50

While takeovers would be a form of temporary nationalization, no one ever refers to FDIC takeovers that way; instead, they are thought of as a government-managed bankruptcy process. A major bank such as Citigroup might have required government conservatorship for months or years, but the goal would have been to restore private ownership when economic conditions allowed. There were both economic and political arguments for this course of action.

The immediate economic argument was that sick banks could only be thoroughly cleaned up via a takeover. Toxic assets needed to be removed from bank balance sheets; but as long as a bank remained independent, any such transaction had to be negotiated, and the bank’s managers (representing the shareholders) could simply hold up the government for a high price, knowing that if the bank failed, other people would be left holding the bag. If the government took over a bank, however, it could transfer the toxic assets to a separate government entity without negotiation, restore the bank to health by adding new capital, and return it to normal operation. Management would be replaced and shareholders wiped out, leaving the bank in the hands of taxpayers, who would get at least some of their money back when the bank could be sold into private hands. (Alternatively, the government could have simply bought a struggling bank at market value; at one point in March 2009, the market value of all of Citigroup’s common stock fell below $6 billion.)

51

The toxic assets could be parked on the balance sheet of the U.S. government, which could hold them indefinitely and, if necessary, absorb the losses they entailed.

The longer-term economic argument was that a takeover was necessary to remove moral hazard—the temptation for bank executives (and shareholders) to take risky gambles, knowing that they would benefit from success but that taxpayers would bear the losses in case of failure. After the Lehman bankruptcy, the government’s policy was that no major bank would be allowed to fail—and every bank CEO knew it—even while smaller banks were failing by the dozens. By contrast, major bank takeovers would send the message that there was a penalty for failure, giving executives and shareholders the incentive to avoid excessive risk, and giving creditors the incentive to be more careful with their money.