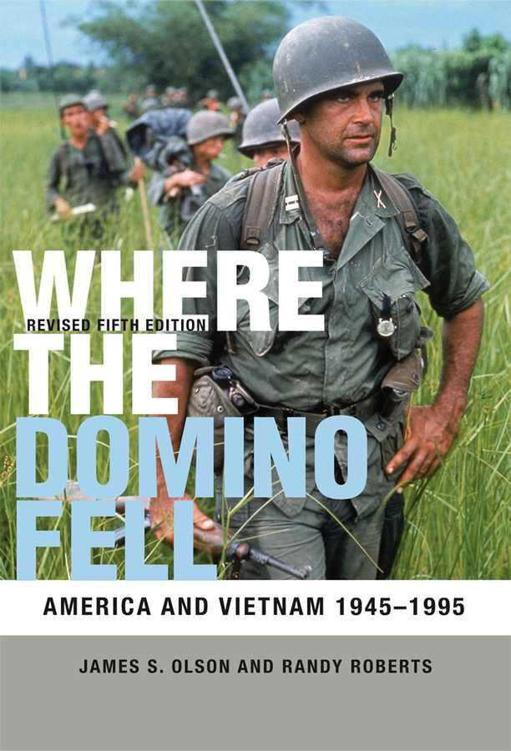

Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

Contents

1 Eternal War: The Vietnamese Heritage

2 The First Indochina War, 1945–1954

3 The Making of a Quagmire, 1954–1960

4 The New Frontier in Vietnam, 1961–1963

5 Planning a Tragedy, 1963–1965

7 The Mirage of Progress, 1966–1967

8 Tet and the Year of the Monkey, 1968

9 The Beginning of the End, 1969–1970

10 The Fall of South Vietnam, 1970–1975

11 Distorted Images, Missed Opportunities, 1975–1995

Glossary and Guide to Acronyms

© 2008 by James S. Olson and Randy Roberts

BLACKWELL PUBLISHING

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

The right of James S. Olson and Randy Roberts to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks, or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Fifth edition published 2006 by Brandywine Press as

Where the Domino Fell:

America and Vietnam

1945–2006

Revised edition published 2008 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

3 2009

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Olson, James Stuart, 1946–Where the domino fell: America and Vietnam, 1945–1995/James S. Olson, Randy Robert. — Rev. 5th ed.

p. cm.

Previously published: Brandywine Press, c2006. 5th ed.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-8222-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Vietnam War, 1961–1975—United States.

2. Vietnam—History—1945–1975. 3. Vietnam—History—1975– 4. Vietnam—Foreign

relations—United States. 5. United States—Foreign relations—Vietnam. I. Roberts,

Randy, 1951– II. Title.

DS558.O45 2008

959.704′3373—dc22 2007043410

Preface

The earliest Rambo movie could almost be taken as an antiwar film. Sylvester Stallone’s John Rambo in

First Blood

is a troubled Vietnam veteran hunted by backwater police and gun wielders of a type ordinarily identified with blood-hungry patriotism. If that is the message, the producers of the Rambo movies apparently later changed their focus. In his return to the screen, Rambo is a vehicle for hyperpatriotic fantasies, a muscled and fearless avenger of freedom against Vietnamese Communists, Soviet invaders of Vietnam, and surely any other enemies of the American Way. The introspection that makes its tentative, half-articulate presence in

First Blood

gives way to a dreamscope of retaliation and triumph.

John Rambo as Stallone plays him is a contradictory symbol of what Americans frustrated by their country’s failure in Vietnam think should have been done there. The more massive deployment of force that they are convinced could have achieved victory would be technological. But Rambo pits brain and sinew against the superior fire-power of his enemies; he is our Vietcong guerrilla. That confusion of image, coupled with the half-start in

First Blood

toward a quite different sensibility about the Vietnam experience, suggests the difficulty that Americans have had in getting a clear grasp not only of the war itself but of their feelings about it.

That, so we hope to show throughout this book, had been the trouble from the beginning. War is, above all else, a political event. Wars are won only when political goals are achieved. Troops and weapons are—like diplomacy and money—essentially tools to achieve political objectives. The United States went into Indochina after World War II with muddled political objectives. It departed in 1975 after a thirty-year effort with political perceptions as blurred as they had been in the beginning. The war was unwinnable because the United States never decided what it was trying to achieve politically.

We are grateful to the reference librarians at Sam Houston State University and Purdue University for their assistance. We appreciate the help of Louise Waller and Lynnette Blevins. We would also like to thank these reviewers who offered useful comments: Truman R Clark, Tomball College; Anthony O. Edmonds, Ball State University; Ben F. Fordney, James Madison University; Katherine K. Reist, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown; and Clifford H. Scott, Indiana University—Purdue University at Fort Wayne. We are indebted to the hundreds of students in our Vietnam War classes who have helped us shape our own ideas about the war.

James S. Olson

Randy Roberts

Prologue: LBJ and Vietnam

On November 22, 1963, as his plane taxied down the runway at Andrews Air Force Base, President Lyndon B. Johnson could have counted up the days in his head. President John F. Kennedy had died only a few hours before. The assassination fulfilled Johnson’s lifelong dream to become president of the United States, but in his heart sadness competed with ambition. The presidential election of 1964 was less than a year away, and the Twenty-Second Amendment allowed him to run in his own right, legitimize his presidency, and then seek re-election in 1968. If he astutely shuffled the deck of Washington politics, he could live in the White House until January 21, 1973, not quite the thirteen-year reign of Franklin D. Roosevelt, but long enough to distinguish him in history. Lest he appear inappropriately political, Johnson kept a low profile while the nation mourned Camelot.

On January 1, 1964, however, Johnson greeted the new year with relief and confidence, or perhaps hubris, possessed only by anyone out to change the world. With JFK interred at Arlington National Cemetery, the eternal flame already burning over his grave, and the horrific events of November 1963 receding somewhat into the past, the president finally could think, and talk, about the future. Desperate for approval and obsessed with his place in history, he yearned to join the ranks of George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, whom historians universally regarded as the nation’s greatest presidents. On the foundation of Roosevelt’s New Deal and Truman’s Fair Deal, he intended to build the Great Society, where prosperity replaced poverty and tolerance quenched the fires of racism. He began mulling around what would become the War on Poverty, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Had Vietnam not spun out of control, Johnson might have joined the pantheon of greatness, but Indochina and its miseries would steadily crowd out any good he achieved.

Early in February 1964, just three months in office, the president ordered the withdrawal from Vietnam of all American dependents. The Vietcong threatened Americans there, and the country was not secure. The United States had nearly 15,000 troops in South Vietnam, but the Vietcong, or “Charlie” as they became to be known, controlled the countryside and the night. Worse is that North Vietnamese regular soldiers were infiltrating South Vietnam. In Saigon, rebellions and coups created a musical-chairs government providing abundant fodder for political satirists and ambitious Republicans.

Already worrying that foreign affairs, in which Johnson had little interest, were distracting Americans from more important tasks, the president turned to his closest advisors. On March 2, 1964, after another coup d’etat in Saigon, Johnson met in the Oval Office with his aide McGeorge Bundy. “There may be another coup, but I don’t know what we can do,” the president complained. “If there is, I guess that we just . . . what alternatives do we have then? We’re not going to send our troops there, are we?” Two months later, Johnson learned that 20,000 Vietnamese, many of them civilian victims of American firepower, had died in 1963, compared to 5,000 in 1962. Calling on Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, he asked whether he should go public with the news. “I do think, Mr. President,” McNamara replied, “that it would be wise for you to say as little as possible [about the war]. The frank answer is we don’t know what’s going on out there.” In subsequent weeks, the president’s concern deepened. “I stayed awake last night thinking of this thing,” he told Bundy in May. “It looks to me like we’re getting into another Korea. . . . I don’t think we can fight them 10,000 miles away from home. . . . I don’t think it’s worth fighting for. . . . It’s just the biggest damned mess I ever saw.” Although the secretary of defense admitted that he did “not know [what was] going on over there” and the president did not consider Vietnam “worth fighting for,” both behaved as if the future of the republic were at stake, investing hundreds of billions of dollars and the soul of a generation. Between 1964 and 1975, Vietnam consumed the lives of more than 58,000 American soldiers and upwards of three million Vietnamese. Today, in 2006, Vietnam stands as a relic of the Cold War, one of a handful of countries still wedded to Marx, Lenin, and May 1st renditions of the Communist

Internationale

. If anything, the war made Vietnam

more

dedicated to Communism, not less.

Forty years after admitting complete ignorance of Vietnam, Robert McNamara released his memoirs, a book “I [had] planned never to write,” he admitted. No wonder. In a warning to future presidents and policymakers, he confessed to monumental arrogance. “We viewed . . . South Vietnam in terms of our own experience,” he wrote. “We saw in them a thirst for—and a determination to fight for freedom and democracy. . . . We totally misjudged the political forces in the country . . . We underestimated the power of nationalism to motivate a people. . . . [We exhibited] a profound ignorance of the history, culture, and politics of . . . the area . . . We failed to recognize the limits of modern, high-technology military equipment. . . . We [forgot] that U.S. military action—other than direct threats to our own security—should be carried out only in conjunction with multinational force supported fully . . . by the international community. . . . External military force cannot substitute for the political order and stability that must be forged by a people for themselves. . . . The consequences of large-scale military operations . . . are inherently difficult to predict and to control. . . . These are the lessons of Vietnam. Pray God we learn them.”

The one war in three decades in which the United States had probably done far more good than harm turned unpopular simply because it was not easy enough. The Vietnam syndrome had never left and the Iraq War (2003-) seems unlikely to vanquish it.