Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 (5 page)

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

Ho Chi Minh had no illusions about why the Americans might be willing to help him. They opposed Japan’s expansion into Indochina in 1940 and 1941 not because of any sympathy with the national aspirations of the Vietnamese. Instead, the United States had been worried about its own access to the French rubber plantations, about British and Dutch oil reserves in Malaya and the East Indies, about the future of the Philippine Islands, and about the fate of the Open Door policy in China. But Ho thought that perhaps the Americans might be willing, if not to liberate Vietnam from the French, at least to help expel the Japanese invaders.

So Ho Chi Minh sought American assistance. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, wanted to develop good intelligence sources in Southeast Asia. Ho made himself available, promising to return downed American fliers and escaped prisoners of war as well as provide information on Japanese troop movements. He wanted arms shipments, first to fight the Japanese and then the French. After securing a promise that the weapons would be used against the Japanese and not the French, the OSS airlifted 5,000 guns to the Vietminh. The OSS agent who brought the guns found Ho Chi Minh “an awfully sweet old guy. If I had to pick out one quality about that little old man sitting on his hill in the jungle, it was his sweetness.”

Steely resolve undergirded the sweetness, and Ho Chi Minh’s associates shared it. Vo Nguyen Giap, the lawyer and history teacher turned revolutionary, emerged as a brilliant military tactician, and from that mountain cave he expanded Vietminh power into the other northern provinces. By 1945 the Vietminh exercised widespread authority in Cao Bang, Phong Tho, Ha Giang, Yen Bay, Tuyen Quang, and Bac Kan provinces. Ho, not France or Japan, ran those provinces. Pham Van Dong led the effort to recruit more peasant soldiers into the Vietminh, and on several occasions whole garrisons deserted the French and came over.

By the spring of 1945, Giap was itching for a large-scale military effort. Ho Chi Minh, jpgted with an uncanny sense of timing, was more cautious, not wanting to see a repeat of the Nghe An slaughter of 1930. The Vietminh should stay with their guerrilla tactics, attacking French and Japanese forces only when victory was certain, not taking unnecessary risks. The Vietminh should be, Ho said, “like the elephant and the tiger. When the elephant is strong and rested … we will retreat. And if the tiger ever pauses, the elephant will impale him on his mighty tusks. But the tiger will not pause and the elephant will die of exhaustion and loss of blood.”

Ho Chi Minh persuaded Giap to continue to fight like a tiger, not like an elephant. A large-scale military confrontation was probably unnecessary anyway. By 1945 the Americans were pounding the last nails into the Nazi coffin in Europe, and they were preparing an invasion of Japan. With the Japanese empire collapsing and the French empire still in limbo, Ho believed that “we will not even need to seize power since there will be no power to seize.” Why waste men and resources in a military escalation when victory was at hand?

Suddenly, in August 1945, after the Americans dropped nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war was over. Bao Dai, the last Vietnamese emperor whom Japan recognized as a puppet head of state, tried to assert himself as the leader of the new nation. But on August 17, 1945, when Bao Dai supporters held a rally in Hanoi, 150,000 people showed up, many of them waving Vietminh flags. Soon the Vietminh leaders had the crowd marching through the streets of Hanoi, leaving the court mandarins sitting alone on an empty dais. In Vinh, Hue, Saigon, Haiphong, Danang, and Nha Trang, the Vietminh staged similar people’s rallies.

Two days later, a few thousand Vietminh soldiers took control of Hanoi. Emperor Bao Dai, ensconced in the imperial palace at Hue, sent a message to the French warning them that their return to Vietnam would be doubtful at best in face of “the desire for independence that has been smoldering in the bottom of all hearts.” If the French colonial apparatus is reconstructed, he said, “it will no longer be obeyed; each village would be a nest of resistance, every enemy a former friend.” When Bao Dai proposed a coalition government with the Vietminh, he was roundly rejected. On August 25, 1945, Bao Dai abdicated the Vietnamese throne. Ho entered Hanoi the same day, wearing a brown canvas shirt, short pants, and a brown pith helmet. A week later, on September 2, he announced the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam with a simple message:

We hold these truths that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness…

The French have fled, the Japanese have capitulated, Emperor Bao Dai has abdicated; our people have broken down the fetters which for over a century have tied us down; our people have at the same time overthrown the monarchic constitution that reigned supreme for so many centuries and instead have established the present Republican government.

At independence celebrations later that day, United States military officials were invited guests. A Vietminh band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Washington was a friend. Vietnam was free. Or so Ho Chi Minh—perhaps tentatively—thought.

2

The First Indochina War, 1945–1954

In war, a great disaster always indicates a great culprit.

—Napoleon, 1813

As artillery shells burst relentlessly on the base at Dienbienphu, Colonel Charles Piroth, the French artillery commander, sank into a deep depression. He had lost his left arm to German shrapnel during World War II, but his commitment to soldiering was so intense that his superiors allowed him to continue in the military. For months Piroth bragged that the end was near for the Vietminh, that they would not be able to go toe to toe with his “big guns” But on March 15, 1954, Piroth realized the truth. He apologized to his comrades, claiming that “it is all my fault,” lay down on the cot, held a grenade with his hand, and pulled the pin with his teeth.

Ten years earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt could have predicted a Dienbienphu of some sort. He believed World War II would destroy European colonialism. In March 1943 Roosevelt suggested to the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, that when the war was over Indochina should be placed under international trusteeship. In a private conversation with Secretary of State Cordell Hull in 1944, the president remarked, “France has had the country—thirty million inhabitants—for nearly one hundred years, and the people are worse off than they were at the beginning . . . . The people of Indochina are entitled to something better than that” Eventually, Roosevelt backed down, primarily because of intense British and French opposition.

Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and the new president did not share his concern. Southeast Asia was another world to Harry Truman. Born and reared in Missouri, Truman had the traditional strengths—and a few of the weaknesses—of the Midwest. Decent, honest, hard working, he took a man at his word and the world as he found it.

Harry’s father, who had a speculator’s optimism, had been prone to economic failures, and by the time Truman graduated from high school there was no money for college. He worked in a bank for a while, then he farmed a full section of land. When President Woodrow Wilson asked for a declaration of war against Germany in 1917, Truman left the plow and picked up a rifle. The war took him to France, where as a captain he successfully commanded troops in battle.

Peace returned Truman to his childhood love, and the newlyweds moved to Kansas City, where he opened a haberdashery. The store went bankrupt in 1922, and for the next twenty years—almost to the time he became president—Truman was strapped for money. And so he turned to politics. There he discovered his métier. Equipped with valuable political assets—honesty, dedication, and a likeable personality—Truman rose through the Kansas City political machine. In 1934 he won a seat in the United States Senate, where he was a loyal if undistinguished party man. In 1944 the Democratic party turned to the well-liked but obscure Truman for the vice-presidential nomination; he seemed the candidate least likely to hurt FDR in the election. The American electorate responded with an amazed “Who’s Truman?” Even John Bricker, the Republican vice-presidential candidate, remarked in a press conference, “Truman—that’s his name, isn’t it? I never can remember that name” On April 12, 1945, people started remembering the name.

Grave matters greeted the new president. Germany was in flames but not yet defeated. Japan was losing the war but refused to entertain the fact. There were troubles in Palestine, a meeting was scheduled with Joseph Stalin, and, of course, there was the entire question of the bomb. Truman faced difficult and momentous decisions. Indochina was not one of them. At the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, the Allied governments quickly worked out a plan for the Japanese surrender in Indochina. The Chinese would accept the surrender of Japanese forces north of the sixteenth parallel, and the British troops would land in Saigon and deal with the Japanese south of the line. What Truman and the Allies did not understand is that they would have to come to terms with Ho Chi Minh.

Whatever hopes Ho had for securing American assistance died in anticommunist paranoia. After the defeat of Germany and Japan, President Truman and American policymakers began looking at the Soviet Union as a successor to the Axis powers in threatening world peace. They wanted to rebuild Western Europe and thereby create an economic and military barrier to Soviet expansion: The fulcrum of a stable Western Europe was France. But the French were still irritated over Roosevelt’s position on Indochina. The State Department urged Truman to repair the rift by assuring France that the United States would not prevent a French return to Indochina. Truman acquiesced in the revival of the empire. In the summer of 1945 he told Charles de Gaulle that the United States would not undermine the French there. And as the French economy staggered and the communist party there gained strength, moderate French politicians warned that even the most benign discussions of colonial independence played into the hands of the communists.

Ho Chi Minh was prepared to go it alone if necessary. World War II had created an unprecedented opportunity for him. When the Vietnamese saw Japanese troops defeating French soldiers, the myth of French superiority vanished. The service that the French bureaucracy and military in Vietnam thereupon did for Japan deepened popular hatred of France. In 1943 Japan ordered French soldiers to seize the Vietnamese rice harvest for export to Japan and for fuel in Vietnamese factories. Small farmers went bankrupt the first year and starved to death in 1944. Somewhere between 500,000 and two million Vietnamese men, women, and children died in the famine. Ho used the suffering to build his movement. His guerrillas attacked granaries and distributed rice to peasants. They assassinated local landlords along with Vietnamese officials working for the French and the Japanese. Vietminh political organizers spread out into central and south Vietnam preaching nationalism. At the war’s end, more than 500,000 people in Vietnam considered themselves loyal to Ho. The Vietminh ruled whole sections of the country as a quasi-government. By the end of the 1945, Ho would have 70,000 followers under arms.

On September 13, 1945, the British under General Douglas D. Gracey entered Saigon with 2,000 Indian troops, most of them famed Gurkha soldiers. Another 18,000 were scheduled to arrive soon. General Lu Han left southern China with 200,000 soldiers and entered Tonkin on September 20. Most of the Chinese troops were barefoot and starving. When they reached the shops in Tonkin, they ate everything in sight, including bars of soap and wrapped packages, which they had never seen before and mistook for food. Sporadic fighting broke out between the ancient enemies. A month before, Ho had marched triumphantly into Hanoi, convinced that independence was imminent. Now he faced 20,000 British troops, 200,000 Chinese and several thousand unarmed French.

Ho Chi Minh’s dream of independence was quickly fading. General Gracey had no sympathy for the Vietminh. Two weeks before arriving in Saigon, he announced that “civil and military control by the French is only a question of weeks” Gracey rearmed French troops so they could protect French citizens from the Vietminh. On September 22, the French rioted in Saigon, attacking police stations, stores, and private homes, and mugging or shooting Vietnamese civilians on the streets. On September 24, the Vietminh declared a general strike. Water and electricity went off in Saigon, trams stalled in their tracks, rickshaws disappeared, and Vietminh roadblocks paralyzed commercial traffic. Vietminh agents went into a French suburb and murdered 150 people. Gracey rearmed Japanese soldiers, and the combined force of Japanese, Gurkha, and French troops went after the Vietminh.

There was a small American contingent in Saigon. Prime within it was A. Peter Dewey, who had parachuted into Tonkin in 1945 to harass the Japanese, and as head of the OSS team in Saigon he soon developed a close relationship with Ho Chi Minh. An outspoken opponent of French imperialism, Dewey clashed repeatedly with Gracey. Their personal battle came to a head late in September when Gracey would not let Dewey fly the American flag on the fender of his OSS jeep. On the way to Tan Son Nhut airport in Saigon on September 26, 1945, Vietminh soldiers fired on the flagless jeep, killing Dewey instantly. Just before leaving for the airport, Dewey had written, “Cochin China is burning, the French and British are finished here, and we ought to clear out of Southeast Asia” When he learned of Dewey’s death, Ho Chi Minh formally apologized. Gracey, to the contrary, remarked that Dewey “got what he deserved” A. Peter Dewey was the first United States soldier to die in Vietnam.

The Vietminh were also on the run in Tonkin, where Chinese troops removed the Vietminh from power and replaced them with a group favorable to the anticommunist Chinese leader Jiang Jieshi and wanting Vietnamese independence without communism. By the end of September, while British, French, and Japanese troops hounded the Viet-minh in southern Vietnam, the Chinese reduced Vietminh-controlled territory in Tonkin. In just a month, Ho found himself dealing with all of Vietnam’s enemies—the Chinese, French, and Japanese—as well as the British.

Although Great Britain was officially neutral about the French return to Indochina, most British officials were worried about their own empire. Insurgent nationalists were active in Malaya and Burma, and Mohandas Gandhi was steadily gaining power in India. When their responsibility for disarming Japanese troops ended in December 1945, the British withdrew from southern Vietnam. Each departing group of British-Indian troops was replaced by French soldiers wearing American fatigues, helmets, boots, and ammunition belts, carrying M-1 carbines, and driving Jeeps and Ford trucks. In Tonkin, the Chinese and French reached a formal agreement in February 1946: China would withdraw from Tonkin, and France would surrender the commercial concessions a Franco-Chinese treaty had granted in the 1890s. The last Chinese troops were out of Vietnam in October.

The French were back, and while most of Ho Chi Minh’s colleagues opposed rapprochement, his political instincts dictated compromise. General Jacques Philippe Leclerc, temporary head of French military forces in Vietnam, also favored compromise. Even though he had 35,000 soldiers at his disposal, Leclerc had no enthusiasm for fighting an open- ended war against the Vietminh. Late in January, he toured the Mekong Delta and the Iron Triangle, a Vietminh stronghold twenty miles northwest of Saigon. “Fighting the Viet Minh,” Leclerc decided, “will be like ridding a dog of its fleas. We can pick them, drown them, and poison them, but they will be back in a few days” On February 5, 1946, Leclerc remarked, “France is no longer in a position to control by arms an entity of 24 million people”

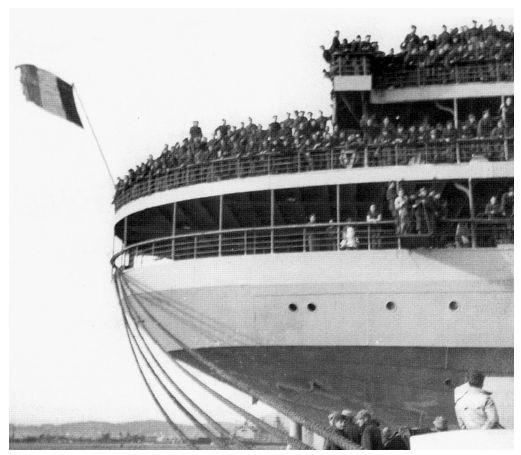

January 12, 1947—Some of the 8,000 French troops aboard the

Ile

de France

prior to departure from Toulon Harbor for duty in Indochina.

(Courtesy, AP/Wide World Photos.)

On March 6, 1946, the French and Vietminh negotiated the Franco-Vietminh Accords. France extended diplomatic recognition to Ho Chi Minh’s regime—calling it a “free state . . . within the French Union”— and promised to hold free elections in the “near future” to determine whether Cochin China, as the southern part of Vietnamese territory had been called, would come under Ho’s control. Ho agreed to have 25,000 French troops replace Chinese soldiers north of the sixteenth parallel and stay until 1951. Both sides consented to have a Vietminh delegation travel to Paris later in the year to work out details of the agreement. But when Ho Chi Minh went to Paris in the summer of 1946, he was in for a big surprise. Georges Thierry D’Argenlieu was the culprit.

After graduating from the French Naval Academy, D’Argenlieu had taken vows in the Carmelite Order in 1920 but then returned to active naval duty in 1940. In 1943 he became commander in chief of the Free French Naval Forces. D’Argenlieu was a devout Roman Catholic, a man who lived permanently in the past. D’Argenlieu believed that Adolf Hitler’s victory over the French had been a fluke, a brief pause in the reign of France as the premier nation on earth. Buoyed by the Allied victory in 1945, D’Argenlieu expected France to return to its former splendor. With that vision, he became high commissioner for Indochina in August 1945.

On June 1, 1946, the day after Ho Chi Minh sailed for Paris, D’Argenlieu created the Republic of Cochin China, a new, separate colony in the French Union. Ho Chi Minh felt “raped” Unification was as important to him as independence. In fact, the two were for him inseparable, not only because his nationalism extended to include a larger Vietnam but because northern Vietnam was overpopulated and poor, unable to feed itself, while the nutrient-rich Mekong Delta produced rice surpluses. To keep Ho Chi Minh away from the Vietnamese émigré community, French officials moved him out to Biarritz in southwest France. The conference was held out of the press limelight at the isolated Fontainebleau Palace. For eight weeks Ho tried to get France to recognize Vietnamese independence, but the French preferred total control over French colonies. Desperate for assistance, Ho contacted the United States embassy, promising to open up Vietnam to American investment and lease a naval base at Cam Ranh Bay in return for help in keeping the French out. Rebuffed, he remarked to an American reporter, “We . . . stand quite alone; we shall have to depend on ourselves” Before returning to Hanoi in mid-September, Ho Chi Minh signed a document in which France agreed to a unification referendum in Cochin China in 1947, but he had few illusions about France’s real intentions. During his last meeting with Georges Bidault, the French prime minister, on September 14, 1946, Ho warned: “If we must fight, we will fight. You will kill ten of our men, and we will kill one of yours. Yet, in the end, it is you who will tire”