Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 (7 page)

Read Where the Domino Fell - America And Vietnam 1945-1995 Online

Authors: James S. Olson,Randy W. Roberts

Tags: #History, #Americas, #United States, #Asia, #Southeast Asia, #Europe, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #World, #Humanities, #Social Sciences, #Political Science, #International Relations, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Asian, #European, #eBook

When North Korea invaded South Korea in June 1950, the Truman administration became all the more convinced that the Soviet Union wanted all of Asia. Led by the United States, the United Nations pledged to defend South Korea. Besides sending troops to Korea, Truman increased the American commitment to France, sending more than $133 million in Indochina aid at the end of the year. He extended another $50 million for economic and technical assistance. A contingent of DC-3 Dakota aircraft landed in Saigon in June. Waiting on the runway with paintbrushes, the French enraged American pilots when they replaced the aircrafts' white star markings with the French tricolor insignia. Late in November, Chinese troops joined the Korean War, killing thousands of UN troops. To most Americans, the international communist conspiracy was well under way.

In Hanoi, Vo Nguyen Giap was not thinking about any international communist conspiracy. From Mao Zedong’s writings on revolutionary warfare, Giap developed a three-stage formula for defeating the French. Beyond that, he had no passionate interest in the spread of communism.

During the first stage that the Vietminh strategist projected, the insurrectionists would just survive, avoiding confrontations until they built up their reserves. If they could achieve surprise and complete superiority, they would strike, but otherwise the Vietminh bided their time Giap’s fear of premature battle was not sentimental. He possessed a unique philosophy about death. “Every minute,” he remarked to a French reporter, “hundreds of thousands of people die on this earth. The life or death of a hundred, a thousand, tens of thousands of human beings, even our compatriots, means little” What Giap did not want was an engagement that destroyed his fledgling army. Stage one characterized Vietminh operations in 1946 and 1947.

The second stage employed guerrilla tactics—ambushes, road destruction, hit-and-run attacks, and assassinations. At night the Vietminh placed booby traps along French patrol routes. Their favorite ones were sharpened bamboo “punji stakes” dipped in human feces or poison and driven into holes or rice paddies, or attached to bent saplings; hollowed – out coconuts filled with gunpowder and triggered by a trip wire; walk bridges with ropes almost cut away so they would collapse when someone tried to cross; a buried bamboo stub with a bullet on its tip, activated when someone stepped on it; the “Malay whip log,” attached to two trees by a rope and triggered by a trip wire; boards studded with iron barbs and buried in stream beds and rice paddies. In 1948 and 1949 Vo Nguyen Giap’s second stage was under way.

By 1949 Giap thought he was almost ready for the third stage. He wanted a real fight with the French Expeditionary Corps. Between 1945 and 1947, he had built the People’s Army from a ragtag group of 5,000 to more than 100,000, most of them irregular troops but also including thousands of highly disciplined, well-trained Vietminh soldiers. Events in 1949 made the general offensive even more inviting. Mao Zedong’s victory gave Giap a sanctuary at his rear. Vietnamese peasants constructed four roads from the Chinese border to staging areas, and Chinese and Soviet supplies began to arrive. By 1950 the Vietminh had five fully equipped infantry divisions, along with an artillery and engineering division. It was time for what Giap termed the “general counter- offensive”

Giap set his sights on the French outpost at Dong Khe. The hedgehog sat astride Route 4, a road the French considered the Vietminh “jugular vein” in northern Tonkin. They reasoned that control of Route 4 would cut Vietminh supply lines from China and stall their troop movements. French truck convoys supplied Dong Khe on a daily basis, but in early 1950 Giap blocked all shipments to the garrison. On May 26, 1950, with monsoon rains drenching the land and Vietminh infantry surrounding the outpost, he began the artillery bombardment. Two days later, thousands of Vietminh soldiers stormed the garrison. It fell on May 28. French paratroopers retook Dong Khe a few days later, but the Vietminh successfully attacked again on September 18. Early in October, they took Cao Bang, the northernmost city on Route 4, and over the next several months the French abandoned Lang Son, their southern outpost on Route 4, and Thai Nguyen, the city on Route 3 between Hanoi and Cao Bang. Vo Nguyen Giap killed or captured 6,000 French troops and eliminated the French presence all along the Chinese border.

The events at Dong Khe left French military planners with the wrong impression. In their final assault, the Vietminh had attacked in massive human wave assaults, infantry troops literally running into and overrunning the French barricades. The Vietminh sustained staggering casualties, but Giap was less concerned with the number of soldiers lost than with their success in achieving the military objective. From the battle of Dong Khe, the French erroneously concluded that in the future, the Vietminh would again employ human wave infantry assaults, as if that was tactical doctrine. That presumption rested on quicksand. In the future, the Vietminh would prove to be quite flexible in attacking fixed French positions.

Heads rolled in Hanoi and Saigon. France fired most senior officials and conferred joint military and political command on General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, who in December 1950 became high commissioner and commander in chief of Indochina. A hero of both world wars, de Lattre had an ability matched by his ego. Handsome, confident, and obsessed with victory, he rebuilt French outposts in the Red River Valley, betting that Vo Nguyen Giap, flushed with success, would push too far.

De Lattre was right. Giap wanted to drive the French back into Hanoi, so he decided to attack Vinh Yen, a reinforced garrison thirty miles northwest of the capital. De Lattre was ready. The Vietminh attacked but failed to overrun the base. Giap tried an attack up the Day River southeast of Hanoi but was repulsed again. He threw the Vietminh against Nam Dinh, a French garrison twenty miles south of Haiphong. Bernard de Lattre, the general’s son, had orders to hold Nam Dinh at all costs. He died obeying his father. By the end of May 1951, 6,000 were dead and Vo Nguyen Giap retreated from Vinh Yen. The general returned to stage two.

De Lattre was barely able to savor the victories. He was terminally ill with stomach cancer and died seven months later in Paris. General Raoul Salan replaced him, but he was little more than a caretaker. De Lattre had created the Vietnamese National Army, on paper a 115,000-man force, to make it appear at least that Bao Dai’s government was really fighting the communists. In the meantime, Giap replenished his divisions. At the end of May 1953 Salan was relieved of his command.

By that time the war was a bottomless pit. Since 1945 the war had cost France 3 dead generals, 8 colonels, 18 lieutenant colonels, 69 majors, 341 captains, 1,140 lieutenants, 9,691 enlisted men, and 12,109 French Legionnaires, along with 20,000 missing in action and 100,000 wounded. Saint-Cyr, the French military academy, was not graduating officers fast enough to replace the dead in Indochina. The military situation was even worse. From the Chinese border in northern Vietnam to the Ca Mau Peninsula on the South China Sea, the Vietminh controlled two-thirds of the country. Their army, including regular and irregular troops, numbered in the hundreds of thousands, and in the words of the journalist Theodore White, “has become a modern army, increasingly skillful, armed with artillery, organized into divisions” French control had been reduced to enclaves around Hanoi, Haiphong, and Saigon, as well as a strip of land along the Cambodian border.

Salan’s replacement was Henri Navarre, a veteran of both world wars who believed French forces could bring the Vietminh to their knees within a year. Navarre had joined the French infantry in 1916 after graduating from Saint-Cyr as a cavalry officer. Except for duty in North Africa during World War II, his career was in army intelligence. Supremely self-confident, dictatorial, and righteously committed, Navarre was an instant celebrity in the French social circuits of Hanoi and Saigon. In both cities he outfitted himself with air-conditioned command posts complete with the best in French wine and cuisine. When he arrived in Saigon to assume his command, Navarre predicted an early end to the war: “Now we can see it clearly—like light at the end of a tunnel”

Navarre decided that French strategy needed an overhaul. After eight years of fighting, the French were no closer to winning than they had been back in 1946. The Vietminh were steadily growing, and Vo Nguyen Giap was preparing to widen the war into Laos. Navarre believed that France was wasting men and resources fighting scattered guerrillas in a conflict that had no end. The key to victory was conventional war. He would seduce the Vietminh into a major engagement where French firepower could annihilate them.

What became known as the Navarre Plan was actually an elaborate military scheme devised in Washington and Paris. Because American troops were tied down in Western Europe and Korea, the United States insisted that France, with massive financial and matériel assistance, take care of Indochina itself. The plan called for a large increase in the size of the Vietnamese National Army and nine new French battalions. Navarre proposed removing his troops from isolated outposts, combining them with the new French troops, and taking the offensive. He hoped to be able to use the Vietnamese National Army elsewhere in Vietnam.

In its first formulation, the Navarre Plan contemplated the Red River Valley as the setting for the massive battle. But in the fall of 1953, Vo Nguyen Giap countered with increased guerrilla attacks throughout the Red River Delta as well as an invasion of central and southern Laos. He also readied three Vietminh divisions for northern Laos. Already at the limits of their economic and military commitment, the French became obsessed with keeping the Vietminh out of Laos, where the Pathet Lao, a guerrilla force backed by the communists, was already causing enough trouble. Navarre began considering a new option—going after the Vietminh in western Tonkin along the Laotian border.

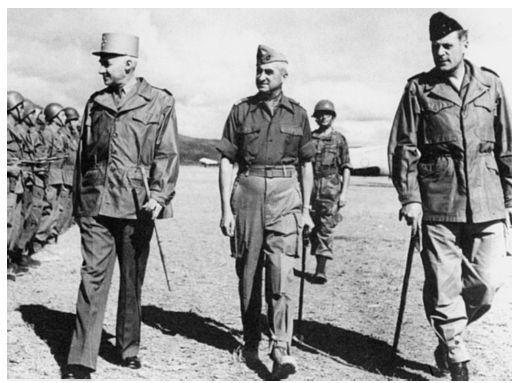

February 1954—General Henri Navarre

(left),

commander of French forces in Indochina, reviews the troops at an inspection of the camp Dienbienphu with Colonel Christian de Castries

(center),

commander of the camp and General René Cogny

(right),

commander of forces in North Vietnam.

(Courtesy, AP/Wide World Photos.)

Navarre scoured the map looking for the perfect place and found it near Laos at the village of Dienbienphu. There Navarre would establish a “mooring point,” a center of operations from which French patrols could go out into the hills in search of the Vietminh. A large French garrison at Dienbienphu would make it more difficult for Giap to ship supplies through Laos to southern Vietnam or invade Laos. Finally, Dienbienphu, was the center of Vietminh opium production; revenues from the drug traffic financed weapons purchases. Suppressing opium production, Navarre hoped

4

would cut Vietminh revenues.

Navarre was convinced that Ho Chi Minh would not be able to abide the French presence at Dienbienphu. In order to push ahead with his plans for domination of Indochina, Ho would have to destroy the French garrison. Anticipating massive, human-wave assaults like the attack the Chinese had launched in Korea and the Vietminh at Dong Khe and Vinh Yen, Navarre planted the base in the center of the valley, with vast stretches of flat territory separating it from the neighboring mountains, where dozens of howitzers were aimed. Colonel Charles Piroth, the one- armed commander of French artillery, predicted that “no Vietminh cannon will be able to fire three rounds before being destroyed by my artillery” If the Vietminh attacked, they had to cross thousands of yards of open fields where French tanks, machine guns, and tactical aircraft would cut them to pieces. With complete air superiority, the French built an airstrip and thought they could hold out indefinitely, resupplying themselves by air from Hanoi.

Navarre wanted to double the size of the Vietnamese National Army to relieve the French Expeditionary Corps of its obligations to fight a nonstop war against Vietminh guerrillas. French advisers would remain in the countryside to work with the Vietnamese National Army in suppressing the guerrillas. At the same time, Navarre assembled a new, powerful army corps to occupy Dienbienphu and engage the Vietminh in battle.

But where would Navarre find the men and the money? In France the Indochina War was increasingly unpopular, swallowing men and matériel with no victory in sight. Conscription was out of the question; there was no way the government could get the necessary legislation through the French National Assembly. Public debate was already at a fever pitch. Instead, Navarre turned to the other colonies, putting together a polyglot army of French Legionnaires and volunteers from France, Lebanon, Syria, Chad, Guadeloupe, and Madagascar. For money Navarre looked to the United States. Ever since 1950, when Congress appropriated the first $15 million, American assistance had steadily increased. Navarre wanted even more, and the administration of Dwight Eisenhower was quick to agree. By the end of 1953 the United States was supplying Navarre with 10,000 tons of equipment a month, at an annual cost of $500 million. That amount increased to $1.1 billion in 1954, nearly 78 percent of France’s war expenses. Navarre had money and men.