13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown (35 page)

Read 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown Online

Authors: Simon Johnson

The full-court lobbying press had an impact. In September 2009, in order to improve the bill’s chances of passage, Barney Frank, the chair of the House Financial Services Committee, eliminated the proposed “plain-vanilla” requirement.

32

(The version of the CFPA proposed in November by Christopher Dodd, chair of the Senate Banking Committee, also left out this requirement.) Small banks also won an exemption in the House from direct examination by the CFPA under most circumstances. But despite the best efforts of the financial sector, the CFPA did emerge intact from the House of Representatives in December 2009. In this case, the Obama administration was willing to confront the banking industry head-on, and Frank was willing to use enough muscle to push it through. The bill introduced by Dodd also includes an independent CFPA, but the sixty-vote threshold in the Senate (to defeat a filibuster) and the apparently unified opposition of the Republican Party’s forty-one senators could mean that the banking lobby will still get its way. The large banks’ grip on Congress has weakened a little, but perhaps not enough.

By consolidating regulatory authority in an agency that is dedicated to consumer protection, the CFPA would have the potential to deter some of the abusive practices that resulted in families losing their homes and fueled the debt bubble of the 2000s. Even if it does become law, however, the CFPA would still face significant obstacles. At the urging of business groups, both the House and Senate versions of the legislation exempted many businesses that provide credit to their customers, such as auto dealers, and even the administration’s original proposal exempted insurance products. These gaps provide opportunities for financial institutions to dodge regulation by redefining their products to fit existing loopholes.

In addition, a consumer protection agency cannot prevent all predatory behavior by financial institutions. The unwitting losers in the financial crisis included many municipalities, pension funds, and other supposedly sophisticated investors who did not understand the products they were buying from their bankers. On the advice of their investment bank, Stifel Nicolaus, five Wisconsin school districts invested $200 million—$165 million of it borrowed from Depfa, an Irish bank—in what they (and their Stifel Nicolaus banker) thought were CDOs. In fact, their $200 million was the collateral for a synthetic CDO, meaning that the school districts were selling insurance on a portfolio of bonds. When the bonds began defaulting, the school districts ended up losing their $35 million and unable to pay off their loan from Depfa. As financial expert Janet Tavakoli said, “Selling these products to municipalities was pretty widespread. They tend to be less sophisticated. So bankers sell them products stuffed with junk.”

33

While businesses, local governments, and institutional investors may not require the same protections as consumers, it is foolish to assume that they will always be able to protect themselves from toxic financial products.

Despite these reservations, a strong, motivated, independent Consumer Financial Protection Agency would serve as a powerful constraint on the ability of financial institutions to take advantage of their customers, discouraging innovations that do not benefit customers and channeling competition into innovations that reduce costs or create new services. The CFPA should also serve as a counterweight within the government to a set of regulatory agencies that have historically seen the world from the perspective of the banks they regulate rather than the customers served by those banks.

However, consumer lending is only one means by which financial institutions can mine the raw material needed for securitization and structured finance. There will always be an unregulated frontier, within our borders or outside them, where banks can place large bets with the potential to go spectacularly badly. A new agency also cannot reverse the political momentum of the last thirty years and dislodge Wall Street from its position of power in Washington. That will require stronger medicine.

TOO BIG TO EXIST

“Too big to fail” was the slogan of the financial crisis. It was the justification for bailing out Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, AIG, Citigroup, and Bank of America (and, extended into the auto industry, General Motors, Chrysler, and GMAC as well). It was the problem that administration officials and congressmen swore they would fix; even bank CEOs agreed, including Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, who wrote, “The term ‘too big to fail’ must be excised from our vocabulary.”

34

The phrase has been around at least since the 1984 government rescue of Continental Illinois, and was the subject of a 2004 book by the president and vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

35

But only in 2008 did it become a pillar of government policy.

Most observers of the financial crisis agree on the basic outlines of the “too big to fail” (TBTF) problem. Certain financial institutions are so big, or so interconnected, or otherwise so important to the financial system that they cannot be allowed to go into an uncontrolled bankruptcy; defaulting on their obligations will create significant losses for other financial institutions, at a minimum sowing chaos in the markets and potentially triggering a domino effect that causes the entire system to come crashing down. The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 accelerated the collapse of American International Group, forcing it into the arms of the Federal Reserve; Lehman’s failure also forced the Reserve Primary Fund to “break the buck,” causing a sudden loss of confidence in all money market funds; in turn the flood of money out of money market funds caused the commercial paper market to freeze, endangering the ability of many corporations to operate on a day-to-day basis. The failure of Lehman also caused large cash outflows from the remaining stand-alone investment banks, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. The sequence of falling dominoes was only stopped by massive government rescue measures, and the panic that occurred despite the government’s intervention helped transform a mild recession into the most severe recession of the postwar period.

What makes a financial institution too big to fail is the amount of collateral damage that its uncontrolled failure could cause. This damage can take several different forms. If a bank defaults on its debt, other institutions holding its debt will lose money, as happened to the Reserve Primary Fund. Although financial institutions generally attempt to avoid holding too much debt from a single issuer for precisely this reason, the problem is magnified by derivatives. Since credit default swaps allow any company to insure any amount of debt issued by any other company, a bank default can cause losses that exceed its actual debt.

Another problem is that a failing institution could have thousands of open transactions with its counterparties, which are largely other financial institutions. (At the time of its collapse, the face value of AIG’s open derivatives contracts was $2.7 trillion—$1 trillion of it with only twelve financial institutions.)

36

For example, a failing bank might have sold credit default swap protection on various securities; its counterparties are assuming that they are perfectly hedged because of those swaps. But when the bank fails, suddenly those hedges vanish, and the counterparties have to take large losses on the underlying securities.

*

These open transactions can take an almost infinite number of forms; in the modern financial world, any financial institution’s position at the end of any given day depends on its counterparties being in business the next day.

Finally, the failure of one bank can cause investors or counterparties to lose confidence in another, similar bank. Because all banks borrow short and lend long, a loss of confidence can kill even a bank that is healthy on paper. After Bear Stearns was sold to JPMorgan Chase in March 2008, all eyes turned to Lehman Brothers; after Lehman failed in September, lack of confidence in Morgan Stanley almost brought it down, and Goldman Sachs was assumed to be next in line.

37

(Merrill Lynch avoided becoming a domino only by selling itself to Bank of America as Lehman collapsed.)

For these reasons, many people have said that the real problem is not the size of a bank (conventionally measured by the total value of its assets), but its interconnectedness.

38

But whatever the term—“too big to fail,” “too interconnected to fail,” “systemically important” (preferred by Ben Bernanke),

39

“tier 1 financial holding company” (preferred by the Treasury Department)

40

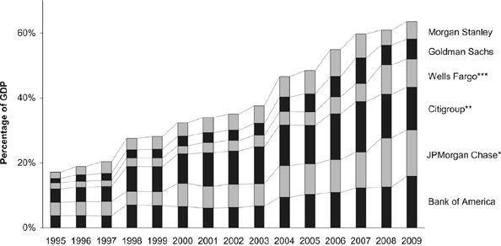

—the fact remains that certain financial institutions cast a sufficiently large shadow over the financial system that they cannot be allowed to fail. As of early 2010, there are at least six banks that are too big to fail—Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo (

Figure 7-1

)—even leaving aside other institutions such as insurance companies.

Figure 7-1: Growth of Six Big Banks

* Chase Manhattan through 1999

** Travelers through 1997

*** First Union through 2000; Wachovia 2001–2007

Source: Company annual and quarterly reports. 2009 is at end of Q3.

Not only is there widespread agreement that several financial institutions are too big to fail, but there is also widespread agreement that this is not good for the financial system or for the economy as a whole. “Too big to fail” creates three major problems for society.

The first problem is that when TBTF institutions do come to the brink of failure, they have to be bailed out, and that usually means they have to be bailed out by the government (and by taxpayers). Even if the government were to decide to wipe out shareholders and replace management, it would still have to bail out the creditors who lent money to the failing bank, since the whole point of the rescue is to limit collateral damage to other financial institutions. A TBTF bank cannot be allowed to go into an ordinary bankruptcy procedure because its creditors and counterparties would be cut off from their money for months, which could be fatal. This means that the government must keep the failing bank afloat and, without a credible threat of bankruptcy to negotiate with, must honor all of the bank’s obligations; in other words, the money the bank lost has to be made up with public funds. This was the case with the AIG bailout, where the government eventually committed $180 billion in various rescue packages to keep AIG alive and pay off its counterparties. This need to protect creditors means that even a government takeover (through an FDIC-style conservatorship) will still result in significant losses to taxpayers.

The second problem is that TBTF institutions have a strong incentive to take excess risk, since the government will bail them out in an emergency. All banks are highly leveraged institutions, which means that they are betting with other people’s money. There are many strategies available to banks that increase returns for shareholders (and executives) while shifting potential losses onto someone else, such as increasing leverage and holding riskier assets. Ordinarily, creditors should refuse to lend money to a bank that takes on too much risk; but if creditors believe that the government will protect them against losses, they will not play this supervisory function. (This is similar to the decision made by foreign investors in emerging markets: it’s always best to lend to the oligarchs, because they are the most likely to be bailed out by the government in a crisis.) There is of course some chance that top executives would lose their jobs in a bailout, but this is more than balanced by the increased upside they gain from taking on more risk. The result is that the largest banks have the most incentive to take risks, and to take risks that would make no economic sense without the government guarantee they get because they are too big to fail. As Larry Summers said in 2000, “It is certain that a healthy financial system cannot be built on the expectation of bailouts.”

41

This problem only gets worse over time. Each time a government bails out its banks, it says, “Never again,” hoping to deter the banks from repeating their past sins. But as Piergiorgio Alessandri and Andrew Haldane of the Bank of England argue, this stance becomes less and less credible: “The ex-post costs of crisis mean such a statement lacks credibility. Knowing this, the rational response by market participants is to double their bets. This adds to the cost of future crises. And the larger these costs, the lower the credibility of ‘never again’ announcements. This is a doom loop.”

42