1968 (14 page)

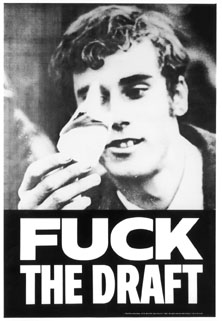

American antiwar poster depicting a draft card being burned

(Imperial War Museum, London, poster negative number LDP 449)

The Selective Service had been planning to call up 40,000 young men a month, but the number was ballooning upward to 48,000. The Johnson administration abolished the student deferment for graduate studies and announced that 150,000 graduate students would be drafted during the fiscal year that would begin in July. This was a severe blow not only for young men planning graduate studies, among them Bill Clinton, a senior at Georgetown’s School of Government who had been appointed a Rhodes Scholar for graduate study at Oxford, but also for American graduate schools, which claimed they would be losing 200,000 incoming and first-year students. One university president, remarkably free of today’s rules of political correctness, complained that graduate schools would now be limited to “the lame, the halt, the blind, and the female.”

At Harvard Law School Alan Dershowitz began offering a course on the legal paths to war resistance. Five hundred law professors signed a petition urging the legal profession to actively oppose the war policy of the Johnson administration. With 5,000 marines in Khe Sanh surrounded by 20,000 enemy troops who could easily be replaced and resupplied from the northern border, the seven days ending February 18 broke a new record for weekly casualties, with 543 American soldiers killed. On February 17, Lieutenant Richard W. Pershing, grandson of the commander of American Expeditionary Forces in World War I, engaged to be married and serving in the 101st Airborne, was killed by enemy fire while searching for the remains of a comrade.

President Johnson was slipping so far in the polls that even Richard Nixon, the perennial loser of the Republican Party, had caught up to him. Nixon’s most feared competitor in the Democratic Party, New York senator Robert Kennedy, who still insisted he was a loyal Johnson Democrat, gave a speech in Chicago on February 8 saying that the Vietnam War was unwinnable. “We must first of all rid ourselves of the illusion that the events of the past two weeks represent some sort of victory,” Kennedy said. “That is not so. It is said the Viet Cong may not be able to hold the cities. This is probably true. But they have demonstrated, despite all our reports of progress, of government strength and enemy weakness, that half a million American soldiers with 700,000 Vietnamese allies, with total command of the air, total command of the sea, backed by huge resources and the most modern weapons, are unable to secure even a single city from the attacks of an enemy whose total strength is about 250,000.”

As the Tet Offensive went on, the question was inescapable: Why had they been caught by surprise? Twenty-five days before Tet, the embassy had intercepted a message about attacks on southern cities including Saigon but did not act on it. A sneak attack during Tet was not even a new idea. In 1789, the year the French Revolution erupted and George Washington took his oath of office, Vietnamese emperor Quang Trung took the Chinese by surprise by using the cover of Tet festivities to march on Hanoi. Not as undermanned as the Viet Cong, he attacked with one hundred thousand men and several hundred elephants and sent the Chinese into a temporary retreat. Wasn’t Westmoreland familiar with this widely known story of Quang Trung’s Tet Offensive? A small statue of the emperor, a gift from a Vietnamese friend, stood in General Westmoreland’s office. Again in 1960, the Viet Cong had scored a surprise victory by attacking on the eve of Tet. Holiday attacks were almost a tradition in Vietnam. North Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap had started his career catching the French by surprise on Christmas Eve 1944.

Now the same General Giap was on the cover of

Time

magazine. On the inside was a several-page color spread, an unusual display for

Time

magazine in the sixties, showing dead American soldiers.

“What the hell’s going on?” said CBS’s Walter Cronkite, reading reports from Saigon off camera. “I thought we were winning the war.”

In a year with no middle ground, Walter Cronkite remained comfortably in the center. The son of a Kansas City dentist, Cronkite was middle class from the Middle West with a self-assured but never arrogant centrist point of view. It became a popular parlor game to guess at Walter Cronkite’s politics. To most Americans Cronkite was not a know-it-all but someone who did happen to know. He was so determinedly neutral that viewers studied his facial movements in the hopes of detecting an opinion. Many Democrats, including John Kennedy, suspected he was a Republican, but the Republicans saw him as a Democrat. Pollsters did studies that showed that Cronkite was trusted by Americans more than any politician, journalist, or television personality. After seeing one such poll, John Bailey, chairman of the Democratic National Committee said, “What I’m afraid this means is that by a mere inflection of his deep baritone voice or by a lifting of his well-known bushy eyebrows, Cronkite might well change the vote of thousands of people around the country.”

Cronkite was one of the last television journalists to reject the notion that he was the story. Cronkite wanted to be a conduit. He valued the trust he had and believed that it came from truthfulness. He always insisted that it was CBS, not just him, that had the trust of America.

The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite,

since it had begun in 1963, was the most popular television news show.

A difference in generations labeled “the generation gap” was not only dividing society, but was apparent in journalism as well. Author David Halberstam, who had been a

New York Times

correspondent in Vietnam, recalled that the older reporters and editors who had come out of World War II tended to side with the military. “They thought we were unpatriotic and didn’t believe that generals lied.” Younger reporters such as Halberstam and Gene Roberts created a sensation, both in public opinion and in journalism, by reporting that the generals were lying. “Then came another generation,” Halberstam said, “who smoked pot and knew all the music. We called them the heads.” The heads never trusted a word from the generals.

Walter Cronkite was from that old World War II generation that believed generals and which Halberstam had found to be such an obstacle when he first started reporting on Vietnam. But, though his thirty minutes of evening news did not reflect this, Cronkite was growing increasingly suspicious that the U.S. government and the military were not telling the truth. He did not see “the light at the end of the tunnel” that General Westmoreland continually promised.

It seemed that in order to understand what was going on in Vietnam, he would have to go and see for himself. This decision worried the U.S. government. They could survive temporarily losing control of their own embassy, but the American people would never forgive their losing Walter Cronkite. The head of CBS News, Richard Salant, had similar fears. Journalists were sent into combat, but not corporate treasures.

“I said,” Cronkite recalled, “well, I need to go because I thought we needed this documentary about Tet. We were getting daily reports, but we didn’t know where it was going at that time; we may lose the war; if we’re going to lose the war, I should be there, that was one thing. If the Tet Offensive was successful in the end, it meant that we were going to be fleeing, as we did eventually anyway, but I wanted to be there for the clash.”

Walter Cronkite never saw himself as a piece of broadcast history or a national treasure, any of the things others saw in him. All his life he saw himself as a reporter, and he never wanted to miss the big story. Covering World War II for United Press International, he had been with the Allies when they landed in North Africa, when the first bombing missions flew over Germany, when they landed in Normandy, parachuted into the Netherlands, broke out of the Bulge. He always wanted to be there.

Salant’s first response was predictable. As Cronkite remembered it, he said, “If you need to be there, if you are demanding to go, I’m not going to stop you, but I think it’s foolish to risk your life in a situation like this, risk the life of our anchorman, and I’ve got to think about it.” His next thoughts were what surprised Cronkite. “But if you are going to go,” he said, “I think you ought to do a documentary about going, about why you went, and maybe you are going to have to say something about where the war ought to go at that point.”

The one thing Dick Salant had been known for among CBS journalists was forbidding any kind of editorializing of the news. Cronkite said of Salant, “If he were to detect any word in a reporter’s report that seemed to have been editorializing at all, personal opinion, he was dead set against it—against doing it at all. Not just mine. I’m talking about any kind of editorializing of anybody.”

So when Salant told Cronkite his idea for a Vietnam special, Cronkite answered, “That would be an editorial.”

“Well,” said Salant, “I’m thinking that maybe it’s time for that. You have established a reputation, and thanks to you and through us we at CBS have established a reputation for honesty and factual reporting and being in the middle of the road. You yourself have talked about the fact that we get shot at from both sides, you yourself have said that we get about as many letters saying that we are damned conservatives as saying that we are damned liberals. We support the war. We’re against the war. You yourself say that if we weigh the letters, they weigh about the same. We figure we are about middle of the road. So if we’ve got that reputation, maybe it would be helpful, if people trust us that much, trust you that much, for you to say what you think. Tell them what it looks like, from your being on the ground, what is your opinion.”

“You’re getting pretty heavy,” Cronkite told Salant.

Cronkite suspected that all the trust he had earned was about to be diminished because he was crossing a line he had never before crossed. CBS also feared that their news show’s top ratings might slip with Walter’s transition from sphinx to pundit. But the more they thought about it, the more it seemed to Cronkite and Salant that in this moment of confusion, the public was hungering for a clear voice explaining what was happening and what should be happening.

When Cronkite arrived in Vietnam, he could not help looking happy, back in war correspondent’s clothes, helmet on head, giving a thumbs-up sign that seemed completely meaningless in the situation. But from the start Cronkite and his team had difficulties. It was hard to find a friendly airport at which to land. When they finally got to Saigon on February 11, they found themselves in a combat zone. Westmoreland briefed Cronkite on how fortunate it was that the famous newsman had arrived at this moment of great victory, that Tet had been everything they had been hoping for. But in fact that same day marked the twelfth day since the Tet Offensive had begun, and though the United States was gaining back its territory, 973 Americans had already died fighting off the Viet Cong attack. Each week was breaking a new record for American casualties. In one day, February 9, 56 marines were killed in the area of Khe Sanh.

In Khe Sanh, where U.S. Marines were dug in near the north-south border, the battle was worsening, and Hanoi as well as the French press were starting to compare it to Dien Bien Phu, where the Vietnamese overran a trapped French army base in 1954. The French press took almost as much glee as the North Vietnamese in the comparison.

In Washington, speculation was so widespread on the idea that the United States might turn to nuclear weapons rather than lose Khe Sanh and five thousand marines that a reporter asked General Earle G. Wheeler, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, if nuclear weapons were being considered for Vietnam. The general reassured no one by saying, “I do not think that nuclear weapons will be required to defend Khe Sanh.” The journalist had not mentioned Khe Sanh in his broad question.

There was a waiting list for correspondents to get a day in Khe Sanh, but Walter Cronkite was not to make the list. It was considered too dangerous. The U.S. military was not going to lose Cronkite. Instead he was taken to Hue, where artillery was smashing the ornate architecture of the onetime colonial capital into rubble. The Americans had once again secured Hue, Cronkite was told, but when he got there marines were still fighting for it. On February 16, U.S. Marines of the 5th Regiment’s 1st Battalion took two hundred yards in the city at a cost of eleven dead marines and another forty-five wounded. It was in Hue that Americans first became familiar with the stubby, lightweight, Soviet-designed weapon, the AK-47, equally effective for a single-shot sniper or spraying ten rounds a second. The weapon was to become an image of warfare in the Middle East, Central America, and Africa.

What most disturbed veteran war correspondent Cronkite was that soldiers in the field and junior officers told him completely different versions of events from those given him by the commanders in Saigon. This was the experience of many who covered Vietnam. “There were so many patent untruths about the war,” said Gene Roberts. “It was more than what is today called spin. We were told things that just weren’t true. Saigon officers and soldiers in the field were saying the opposite. It produced a complete rift between reporters and the U.S. government.”