1968 (46 page)

Conventions chose candidates by a series of ballots—delegate counts, state by state. These ballots would go into the night, ignoring the broadcast needs of prime-time television, until a single candidate had an absolute majority of delegates. Usually the more ballots that took place, the more the front-runner’s support would erode. Rockefeller imagined the delegates turning to him after a few rounds. Reagan fantasized that Rockfeller and Nixon would be deadlocked ballot after ballot until the delegates finally turned to him as a way out. Lindsay, though no one believed it, harbored a similar fantasy about himself.

Nixon won on the first ballot.

The only drama was Nixon’s struggle with Nixon. His political career had been considered over in 1948, when he attacked former State Department official Alger Hiss. It was supposed to be over again in 1952, when he was caught in a fund-raising scandal. And in 1962, when he was defeated for governor of California only two years after losing the presidency to Kennedy, he gave his own farewell to politics. Now he was back. “The greatest comeback since Lazarus,” wrote James Reston in

The New York Times.

Then something weird happened: Nixon, in his acceptance speech, started talking like Martin Luther King. Mailer was the first to notice it, but this was not just one of his famously eccentric imaginings. Nixon, who also adopted the SDS’s two-fingered peace salute, never put limits on what he could co-opt. Martin Luther King in the four months since his death had journeyed from rebel agitator to the heart of the American establishment. His organization was picketing outside the convention hall. Six miles away, Miami was having its first race riot. The governor of Florida was talking about responding with necessary force, and black men were being shot. Richard Nixon was delivering a speech.

“I see a day,” he repeated nine different times in the unmistakably familiar cadence of “I have a dream.” Then, further on in the speech, seemingly enraptured with his own or whomever’s rhetoric, he declared, “To the top of the mountain so that we may see the glory of a new day for America. . . .”

The Republican convention in Miami the second week of August 1968 was a bore that according to pollsters alienated youth, alienated blacks, and excited almost no one. Even the one possibility for drama—the complaints of black groups that black representation was unfairly excluded from the delegations of Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee failed to produce drama because it was quickly glossed over. Norman Mailer wrote, “The complaints were unanimous that this was the dullest convention anyone could remember.” One television critic said the coverage was so long and dull that it constituted “cruel and unusual punishment.” But the boredom helped the Republicans. It kept people from paying attention and consequently kept them from noticing the rioting in the street. A poll taken in segregated white Florida public schools in 1968 had found 59 percent of white students were either elated or indifferent to the news of Martin Luther King’s assassination. While Nixon was being crowned in Miami Beach, Ralph Abernathy, head of the late Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was leading daily black demonstrations outside, and across the bay in the black ghetto called Liberty City, a violent confrontation erupted between police and blacks, with cars overturned and set on fire. National Guard troops were called in. While Nixon was selecting his running mate, three blacks were killed in the Liberty City riot.

There was only the question of vice president left, and logic seemed to dictate a liberal who could pick up the Rockefeller votes—either Rockefeller himself or New York City mayor John Lindsay, who was campaigning hard for the nomination, or Illinois senator Charles Percy. Rockefeller, who had declined to be Nixon’s running mate in 1960, seemed unlikely to accept now.

In the end Nixon surprised everyone—at last a surprise—and picked the governor of Maryland, Spiro T. Agnew. He said he did this to unify the party, but the party could not conceal its unhappiness. The entire moderate half of the party had been ignored. The Republican Party had a ticket that would greatly appeal to white southerners who felt embattled by years of civil rights and to some northern reactionary “law and order” voters who had been angered by the rioting and disorder of the past two years, but to no one else. The Republicans were leaving most of the country to the Democrats. Alabama renegade Democrat George Wallace, an old-time segregationist running on his own ticket, could not only siphon off Democrats, he could also deny the Republicans enough votes to cost them southern states and their whole southern strategy. There was a move to try to force Nixon to pick someone else that was stopped only because Mayor Lindsay, the leading liberal candidate for the job, performed Nixon the service of seconding the Agnew nomination.

Nixon defensively said that Agnew was “one of the most underrated political men in America.” The following day, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the NAACP, one of the most moderate black groups, denounced the ticket, which they termed “white backlash candidates.” Was that bad news for Nixon? Was that even news? Richard Nixon, with few people noticing, had reshaped the Republican Party.

Then on to Chicago—for a convention that would not be boring.

CHAPTER 16

PHANTOM FUZZ DOWN

BY THE STOCKYARDS

Jean Genet, who has considerable police experience, says he never saw such expressions before on allegedly human faces. And what is the phantom fuzz screaming from Chicago to Berlin, from Mexico City to Paris? “We are REAL REAL REAL!!! as this NIGHTSTICK!” As they feel, in their dim animal way, that reality is slipping away from them.

—W

ILLIAM

B

URROUGHS,

“The Coming of the Purple Better One,”

Esquire,

November 1968

There’s nothing unreal about Chicago. It’s quite real. The mayor who runs the city is a real person. He’s an old time hack. I might chastise the Eastern establishment for romanticizing him. The whole “Last Hurrah” aspect. He’s a hack. A neighborhood bully. You have to see him to believe him.

—S

TUDS

T

ERKEL,

interviewed by

The New York Times,

August 18, 1968

People coming to Chicago should begin preparations for five days of energy-exchange.

—A

BBIE

H

OFFMAN,

Revolution for the Hell of It,

1968

E

VERYTHING SEEMED

inauspicious for the Democratic National Convention in Chicago at the end of August. The convention center had burned down, the most exciting candidate had been murdered, leaving mostly a void filled with anger, and the mayor had become notorious for his use of police violence.

Chicago’s McCormick Place Convention Center was what Studs Terkel might have a called “a real Chicago story.” It had been built a few years earlier at a cost of $35 million and named after the notorious right-wing publisher of the

Chicago Tribune,

one of the few backers of the project besides Mayor Daley. Environmentalists fought it as a degradation of the lakefront, and most Chicagoans regarded it as abysmally ugly. Then, mysteriously or, according to some, miraculously, it burned down in 1967, leaving the Democrats without a location and Chicagoans wondering exactly how the $35 million had been spent.

Mayor Richard Daley, who in his 1967 reelection faced what was close to a serious challenge because of the McCormick Place scandal, was not going to let fire or scandal rob his city of a major convention. By the old Union Stockyards, the beef center of America until it was closed down in 1957, stood the Amphitheatre. Miles from downtown, since the closing of the stockyards this had become an out-of-the-way part of Chicago where such events as wrestling and the occasional car or boat show took place. The convention could take place in the Chicago Amphitheatre once Daley had it wrapped in barbed wire and surrounded by armed guards. The delegates could stay, as planned, in the Conrad Hilton Hotel, about six miles away, by the handsomely landscaped downtown Grant Park.

For almost a year, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, and other New Left leaders had been planning to bring people to Chicago to protest. In March they had met in secret in a wooded campground outside Chicago near the Wisconsin border. About two hundred invited activists attended the meeting sponsored by Hayden—among them Davis, David Dellinger, and the Reverend Daniel Berrigan, Catholic chaplain at Cornell. Unfortunately, the “secret meeting” was written about in major newspapers. Davis and others had talked about “closing down the city,” but Mayor Richard J. Daley dismissed such comments as boastfulness. Now they were coming to Chicago: Hayden and Davis and the SDS, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin and the Yippies. David Dellinger and the Mobe vowed to bring in hundreds of thousands of antiwar protesters. The Black Panthers were to have a contingent, too. Dellinger had been born in 1915, and the World War I armistice was one of his earliest memories. Jailed for refusing the draft in World War II, he had almost thirty years of experience demonstrating against wars and was the oldest leader in Chicago. Everyone was going to Chicago, which may have been why Mayor Daley had made such a show of brutality in the riots after King’s shooting in April.

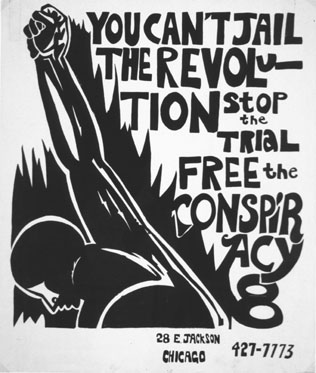

Silk-screen poster protesting the attempt by federal prosecutors to prosecute the leaders of the Chicago convention protesters

(Center for the Study of Political Graphics)

1968 was a hard year to keep up with. Originally the movements were going to Chicago to protest the coronation of incumbent president Lyndon Johnson. McCarthy and whatever delegates he had would protest inside the convention, and the demonstrators would be outside, before the television cameras, reminding America that there were a lot of people who were not supporting Johnson and his war. But with Johnson not running, they were coming to Chicago to support McCarthy and the antiwar plank. Then Bobby Kennedy was running, and when for a moment it looked as though he might be winning, some, including Hayden, began to wonder if they would be protesting at all in Chicago. But while Kennedy and McCarthy had been fighting it out in the primaries, Hubert Humphrey—without McCarthy and Kennedy’s armies of devoted volunteers, but with a skilled professional organization—was picking up delegates at the caucuses and meetings of nonprimary states. Once Kennedy was killed, plans turned to bitterness and fatalism. Go to Chicago to stop Humphrey from stealing the convention, to make sure the Democratic platform was antiwar, or . . . go to Chicago because there was nothing else that could be done.

Even by national political convention standards, the media had high expectations for Chicago. Not only were hordes of television and print media planning to be there, but writers were coming, too. Playwright Arthur Miller was a Connecticut delegate for McCarthy.

Esquire

magazine commissioned articles from William Burroughs, Norman Mailer, and Jean Genet. Terry Southern, who had written the screenplay of the antinuclear classic

Dr. Strangelove,

was there, as was poet and pacifist Robert Lowell. And of course Allen Ginsberg was there, half as poet, half as activist, mostly trying to spread inner peace and spirituality through the repetition of long, deep tones: “Om . . .”

A mayor other than Daley might have recognized that bottled pressure explodes and made provisions for a demonstration that some said might involve as many as a million people. It was not necessarily going to be violent, but given the way the year was going, the absence of violence was unlikely. There might have been some tear gas and a few clunked heads, which he could hope to keep off television while the networks were preoccupied by what was certain to be a bitter and emotional fight within the convention.

But Daley was a short, jowly, truculent man, a “boss” from the old school of politics. Chicago was his town, and like a great many Americans with working-class roots, he hated hippies. The first and insurmountable problem: He refused a demonstration permit. The demonstrators wanted to march from Grant Park to the Amphitheatre, a logical choice as the route from the hotel where the delegates were staying to the convention. Daley could not allow this; he could not allow a demonstration from anywhere in downtown to the Amphitheatre. The reason for this was that getting from downtown to the Amphitheatre required passing through a middle-class neighborhood of trim brick houses and small yards called Bridgeport. Bridgeport was Daley’s neighborhood. He had lived there all his life. Many of his neighbors were city workers who got the patronage jobs on which a local Chicago politician built his political base. Nobody was ever able to tabulate how many patronage jobs Daley had handed out. Chicago politics was all about turf. There was absolutely no circumstance, no deal, no arrangement, by which Daley was going to allow a bunch of hippies to march through

his

neighborhood.

The argument that everything that happened in Chicago during that disastrous August convention was planned and under orders from the mayor gains some credibility considering an April antiwar march with an almost identical fate. That time also, no amount of cajoling or imploring could get the marchers a permit from city hall. And that time also, the police suddenly, without warning, attacked with clubs and beat the demonstrators mercilessly.

The demonstrators were not what Daley and the police feared most. They were worried about another race riot, having already had a number of them. Relations between the black community and the city government were hostile; it was summer, the riot season, and the weather was hot and humid. Even Miami, which never had ghetto riots, had one during its convention that year. The Chicago police were ready and they were nervous.

At first, refusing the demonstration permit seemed to work. Far fewer hippies, Yippies, and activists came to Chicago than were expected—only a few thousand. Participants estimated that about half their ranks were local Chicago youth. For the Mobe, it was the worst turnout they had ever had. Gene McCarthy had advised supporters not to come. Black leaders, including Dick Gregory, who went himself, and Jesse Jackson, had advised black people to stay away. According to his testimony in the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial the following year, Jackson, who was already familiar with the Chicago police, had told Rennie Davis, “Probably Blacks shouldn’t participate. . . . If Blacks got whipped nobody would pay attention. It would just be history. But if whites got whipped, it would make the newspapers.”

Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies arrived with a plan, which they called A Festival of Life—in contrast with the convention in the Amphitheatre, which they called A Festival of Death. On the weeklong schedule of events listed on their Festival of Life handout flyers were included the following:

August 20–24 (AM) Training in snake dancing, karate, non-violent self-defense

August 25 (PM) MUSIC FESTIVAL—Lincoln Park

August 26 (AM) Workshop in drug problems, underground communications, how to live free, guerrilla theatre, self-defense, draft resistance, communes, etc.

August 26 (PM) Beach party on the Lake across from Lincoln Park.

Folksinging, barbecues, swimming, lovemaking

August 27 (Dawn) Poetry, mantras, religious ceremony

August 28 (AM) Yippie Olympics, Miss Yippie Contest, Catch the Candidate, Pin the Tail on the Candidate, Pin the Rubber on the Pope and other normal, healthy games

Many of the items were classic Abbie Hoffman put-ons. Others were not. An actual festival had been planned, bringing in music stars such as Arlo Guthrie and Judy Collins. The Yippies had been working on it for months, but the music stars could not be brought in without permits, which the city had been declining to give for months. A meeting between Abbie Hoffman and Deputy Mayor David Stahl was predictably disastrous. Hoffman lit a joint and Stahl asked him not to smoke pot in his office. “I don’t smoke pot,” Hoffman answered, straight-faced. “That’s a myth.” Stahl wrote a memo that the Yippies were revolutionaries who had come to Chicago to start “a revolution along the lines of the recent Berkeley and Paris incidents.”

On the Yippie agenda was an August 28 afternoon Mobe march from Grant Park to the convention. It was the only event for which they had listed a specific time—4:00

P.M.

But the entire program was in conflict with the Chicago police because it was based on the premise that everyone would sleep in Lincoln Park, an idea ruled out by the city. Lincoln Park is a sprawling urban space of rolling hills and shady, sloping lawns, where Boy Scouts and other youth organizations are frequently allowed to hold sleep-outs. The park is a few miles long, but it’s a very quick drive from Grant Park to the Conrad Hilton or, as Abbie Hoffman kept calling it, the Conrad Hitler. Even before the convention began, the police posted signs in Lincoln Park: “Park Closes at 11

P.M.

” When all city avenues were exhausted, the demonstrators turned to federal court to seek permission to use the park. Judge William Lynch, Daley’s former law partner who had been put on the bench by the mayor himself, turned them down.

The events the Yippies did go ahead with were those that would attract television. The snake dance was a martial arts technique supposedly perfected by the Zengakuren, the Japanese student movement, for breaking through police lines. The Yippies in headbands and beads continually practiced against their own lines and failed consistently. But it looked exotic on television, and few crews catching their martial arts practice in the park could resist filming what was reported as hippies practicing martial arts to prepare for combat with the Chicago police. One crew even caught Abbie Hoffman himself participating; he identified himself as “an actor for TV.”

Another event that they did intend to carry out was the nomination of the Yippie candidate for president, Mr. Pigasus, who happened to be a pig on a leash. “The concept of pig as our leader was truer than reality,” Hoffman wrote in an essay titled “Creating a Perfect Mess.” Pig was the common pejorative for police at the time, but Hoffman insisted that in the case of Chicago, the “pigs” actually looked like pigs, “with their big beer bellies, triple chins, red faces, and little squinty eyes.” It was a kind of silliness that was infectious. He pointed out the resemblance of both Hubert Humphrey and Daley to pigs, and the more he explained, the more it seemed that everyone was starting to look like a pig.