1968 (49 page)

CHAPTER 17

THE SORROW OF

PRAGUE EAST

I think that in the long run, our non-violent approach and the moral supremacy of the Czechoslovak people over the aggressor had, and still has moral significance. In retrospect it could be said that the peaceful approach may have contributed to the breakup of the “aggressive” bloc. . . . My conviction that moral considerations have their place in politics does not follow simply from the fact that small countries must be moral because they do not have the ability to strike back at bigger powers. Without morality it is not possible to speak of international law. To disregard moral principles in the realm of politics would be a return to the law of the jungle.

—A

LEXANDER

D

UBČEK,

August 1990

O

N TUESDAY, AUGUST

20, Anton Tazky, a secretary of the Slovak Communist Party Central Committee and a personal friend of Dub ek’s, was driving back to Bratislava from an outlying Slovak district. He saw odd, bright lights, and as he drove closer, realizing that these were the headlights of tanks and military trucks, and that these vehicles were accompanied by soldiers in foreign uniforms, he concluded that he had driven by a movie shoot. He went to bed.

ek’s, was driving back to Bratislava from an outlying Slovak district. He saw odd, bright lights, and as he drove closer, realizing that these were the headlights of tanks and military trucks, and that these vehicles were accompanied by soldiers in foreign uniforms, he concluded that he had driven by a movie shoot. He went to bed.

August 20 was a hazy summer day. Dub ek’s wife, Anna, had been up much of the night before with intense pain from a gallbladder problem. On Tuesday morning Dub

ek’s wife, Anna, had been up much of the night before with intense pain from a gallbladder problem. On Tuesday morning Dub ek took her to the hospital and explained to her that he had an afternoon presidium meeting that would run late and he might not be able to visit her until Wednesday morning. It was the last time the presidium would meet before the Fourteenth Party Congress three weeks later, and Dub

ek took her to the hospital and explained to her that he had an afternoon presidium meeting that would run late and he might not be able to visit her until Wednesday morning. It was the last time the presidium would meet before the Fourteenth Party Congress three weeks later, and Dub ek and his colleagues wanted to use the congress to solidify in law the achievements of the Prague Spring.

ek and his colleagues wanted to use the congress to solidify in law the achievements of the Prague Spring.

Over the weekend, when protesters were just beginning to settle into Lincoln Park and the Chicago police hadn’t yet taken their first good swing, the fate of Prague East, as they called it in Chicago, had already been decided by Brezhnev and Kosygin in Moscow. The Soviets believed that once the Czechoslovakian presidium, already in session, saw the tanks coming, they would oust Dub ek and his team. According to some scenarios, Dub

ek and his team. According to some scenarios, Dub ek and other key figures would quickly be put on trial and executed. The official East German newspaper,

ek and other key figures would quickly be put on trial and executed. The official East German newspaper,

Neues Deutschland,

believing the Soviet plan would work, ran a story the night of the invasion about the uprising and the new revolutionary government that had asked for Soviet military support.

But no new government had been formed, and no one had asked for Soviet intervention. The presidium session, as predicted, went late into the evening. A working supper was served. Two of the members frustrated the others by presenting a proposed text that went back on the progress they had made. But it received little support. At 11:30, without any shift in power, the premier, Old=ich ›erník, called the defense minister and returned to announce, “The armies of the five countries have crossed the Republic’s borders and are occupying us.”

Dub ek, as though alone with his family, said softly, “It is a tragedy. I did not expect this to happen. I had no suspicion, not even the slightest hint that such a step could be taken against us.” Tears began to slide down his cheeks. “I have devoted my entire life to cooperation with the Soviet Union and they have done this to me. It is my personal tragedy.” In another account he was heard to say, “So they did it after all—and to

ek, as though alone with his family, said softly, “It is a tragedy. I did not expect this to happen. I had no suspicion, not even the slightest hint that such a step could be taken against us.” Tears began to slide down his cheeks. “I have devoted my entire life to cooperation with the Soviet Union and they have done this to me. It is my personal tragedy.” In another account he was heard to say, “So they did it after all—and to

me!

” It was as though at that moment, for the first time in his life, he had let go of his father’s dream of the Soviet Union as the future’s great promise. The initial response of many officials, including Dub ek, was to resign, but quickly Dub

ek, was to resign, but quickly Dub ek and the others realized that they could make it far more difficult for the Soviets by refusing to resign and insisting that they were the sole legitimate government. After that, it took only a day for leaders in Moscow to start understanding the terrible mistake the Soviet Union had made.

ek and the others realized that they could make it far more difficult for the Soviets by refusing to resign and insisting that they were the sole legitimate government. After that, it took only a day for leaders in Moscow to start understanding the terrible mistake the Soviet Union had made.

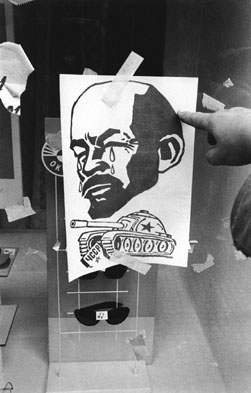

Lenin weeps in a poster taped to a window in Prague after the invasion

(Photo by Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos)

Three days earlier, on August 17, Dub ek had had a secret meeting with Hungary’s Kádár. The Dub

ek had had a secret meeting with Hungary’s Kádár. The Dub ek generation in Prague had little regard for Ulbricht and Gomułka. Zden

ek generation in Prague had little regard for Ulbricht and Gomułka. Zden k Mlyná

k Mlyná , one of the Party Central Committee secretaries, called them “hostile, vain, and senile old men.” Bulgaria’s Todor Zhivkov was closer to Dub

, one of the Party Central Committee secretaries, called them “hostile, vain, and senile old men.” Bulgaria’s Todor Zhivkov was closer to Dub ek in age but was considered dull and possibly stupid. János Kádár, on the other hand, was regarded as an intelligent and like-minded communist who wanted reform to succeed in Czechoslovakia for the same reason Gomułka opposed it: He thought it might spread to his own country. But he had come to realize that he was out of step with the rest of the Hungarian leadership and that he risked bringing Hungary out of step with Moscow. Hungary, having experienced invasion twelve years earlier, was not going to become a rebel state again. Kádár probably knew the decision to invade had already been made or was about to be when he met with Dub

ek in age but was considered dull and possibly stupid. János Kádár, on the other hand, was regarded as an intelligent and like-minded communist who wanted reform to succeed in Czechoslovakia for the same reason Gomułka opposed it: He thought it might spread to his own country. But he had come to realize that he was out of step with the rest of the Hungarian leadership and that he risked bringing Hungary out of step with Moscow. Hungary, having experienced invasion twelve years earlier, was not going to become a rebel state again. Kádár probably knew the decision to invade had already been made or was about to be when he met with Dub ek to warn him and convince him to back away from his positions. He even cautioned Dub

ek to warn him and convince him to back away from his positions. He even cautioned Dub ek that the Soviets were not the men he imagined them to be and that he did not understand with whom he was dealing. It was probably too late, but in any event, Dub

ek that the Soviets were not the men he imagined them to be and that he did not understand with whom he was dealing. It was probably too late, but in any event, Dub ek did not understand Kádár’s subtle but desperate warning.

ek did not understand Kádár’s subtle but desperate warning.