1968 (44 page)

In June thousands of Soviet troops had been allowed into Czechoslovakia for “staff maneuvers.” This was normal, but the quantity, tens of thousands of troops and thousands of vehicles, including tanks, was not. The maneuvers were supposed to end on June 30, and as each July day passed with the troops still there, the population was growing angrier. Clearly stalling, the Soviets presented a steady stream of ridiculous excuses: They needed repairs and so additional “repair troops” began entering, problems with spare parts, the troops needed rest, they were concerned about blocking traffic, the bridges and roads on which they had entered seemed shaky and in need of repairs.

Rumors spread through Czechoslovakia that the trespassing Soviet troops had brought with them printing presses and broadcast-jamming equipment, files on Czechoslovakian political leaders, and lists of people to be arrested.

The Czechoslovakian government demanded the removal of the Soviet troops. The Soviets demanded that the entire Czechoslovakian presidium come to Moscow and meet with the entire Soviet presidium. Prague responded that they thought the meeting was a good idea and “invited” the Soviet presidium to Czechoslovakia. The entire Soviet presidium had never traveled outside the Soviet Union.

Dub ek knew he was playing a dangerous game. But he had his own people to answer to, and they clearly would not accept capitulation. In retrospect, one of the deciding factors that kept the Soviets from giving the invasion order that July was the tremendous unity of the Czechoslovakian people. There had never before really been a Czechoslovakian people. There were Czechs and there were Slovaks, and even among Czechs there were Moravians and Bohemians. But for one moment in July 1968 there were only Czechoslovakians. Even with troops around and within their border, with the Soviet press vilifying them daily, they spoke with one voice. And Dub

ek knew he was playing a dangerous game. But he had his own people to answer to, and they clearly would not accept capitulation. In retrospect, one of the deciding factors that kept the Soviets from giving the invasion order that July was the tremendous unity of the Czechoslovakian people. There had never before really been a Czechoslovakian people. There were Czechs and there were Slovaks, and even among Czechs there were Moravians and Bohemians. But for one moment in July 1968 there were only Czechoslovakians. Even with troops around and within their border, with the Soviet press vilifying them daily, they spoke with one voice. And Dub ek was careful to be that voice.

ek was careful to be that voice.

At almost 3:00 in the morning on July 31, a rail worker and a small group of Slovak steel workers recognized a man out for a walk as First Secretary Comrade Dub ek. Dub

ek. Dub ek invited them to a small restaurant that was open at that hour. “He spent about an hour with us and explained the situation,” one of the workers later told the Slovak press. When they asked why he was out so late, he told them that for the last few weeks he had been sleeping only between 3:00

ek invited them to a small restaurant that was open at that hour. “He spent about an hour with us and explained the situation,” one of the workers later told the Slovak press. When they asked why he was out so late, he told them that for the last few weeks he had been sleeping only between 3:00

A.M.

and 7:00

A.M.

Czech television interviewed Soviet tourists and asked them if they had seen counterrevolutionary activity and if they had been treated well. They all spoke highly of the country and the people and saluted Soviet-Czechoslovak friendship. For four days, the two presidiums met in ›ierna nad Tisou, a Slovak town near the Hungarian-Ukrainian border. On August 2, when the meeting had ended, Dub ek gave a television address in which he assured the Czechoslovakian people that their sovereignty as a nation was not threatened. He also told them that good relations with the Soviet Union were essential to that sovereignty, and he warned against verbal attacks on the Soviets or socialism.

ek gave a television address in which he assured the Czechoslovakian people that their sovereignty as a nation was not threatened. He also told them that good relations with the Soviet Union were essential to that sovereignty, and he warned against verbal attacks on the Soviets or socialism.

The message was that there would be no invasion if the Czechoslovakians refrained from provoking the Soviets. The following day, the last of the Soviet troops left Czechoslovakia.

Dub ek appeared to be reining in free speech. Still, he seemed to have won the confrontation. Sometimes survival alone is the great victory. The new Czechoslovakia had made it through the Prague Spring into Prague summer. Articles were being written around the world on why the Soviets were backing down.

ek appeared to be reining in free speech. Still, he seemed to have won the confrontation. Sometimes survival alone is the great victory. The new Czechoslovakia had made it through the Prague Spring into Prague summer. Articles were being written around the world on why the Soviets were backing down.

Young people from Eastern and Western Europe and North America began packing into Prague to see what this new kind of liberty was about. The city’s dark medieval walls were being covered with graffiti in several languages. With only seven thousand hotel rooms in Prague, there was often nothing available anywhere in the city, although sometimes a bribe would help. A table at one of the few Prague restaurants was getting hard to come by, and a taxi without a fare was a rare sight. In August

The New York Times

wrote, “For those under 30, Prague seems the right place to be this summer.”

PART III

THE SUMMER OLYMPICS

The longing for rest and peace must itself be thrust aside; it coincides with the acceptance of iniquity. Those who weep for the happy periods they encountered in history acknowledge what they want: not the alleviation but the silencing of misery.

—A

LBERT

C

AMUS,

L’Homme révolté—The Rebel,

1951

CHAPTER 14

PLACES NOT TO BE

In the colonies the truth stood naked, but the citizens of the mother country preferred it with clothes on.

—J

EAN

-P

AUL

S

ARTRE,

Introduction to Frantz Fanon’s

The Wretched of the Earth,

1961

E

VERYTHING SEEMED

to get worse in the summer of 1968. The academic year had ended disastrously, with hundreds walking out on Columbia graduation—even though President Kirk did not attend in order to avoid provoking demonstrations. Universities in French, Italian, German, and Spanish cities were barely functioning. In June violent confrontations between students and police erupted in Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo and in Ecuador and Chile. On August 6 a student demonstration in Rio was canceled when 1,500 infantrymen and police with thirteen light tanks, forty armored vehicles, and eight jeeps mounted with machine guns appeared. Often the demonstrations began over very basic issues. In Uruguay and Ecuador the original issue had been bus fares to school.

Even relatively quiet England was at last having its 1968, with students ending the year occupying universities. It had begun in May at the Hornsey College of Art and Design, a Victorian building in affluent north London, where students had a meeting about issues such as a full-time student president and a sports program and ended by taking over the building and demanding fundamental changes in art education. Their demands spread to art schools throughout the country and became a thirty-three-art-college movement. Students at Birmingham College of Art refused to take final examinations. By the end of June students still held Hornsey College.

So little progress was seen in the stalemated Paris peace talks that on the first day of summer

The New York Times

offered Americans a sad crumb of hope in the carefully worded headline

CLIFFORD DETECTS SLIGHT GAIN IN TALKS ON VIETNAM.

On June 23 the Vietnam War edged out the American Revolution as the longest-running war in American history, having lasted 2,376 days since the first support troops were sent in 1961. On June 27 the Viet Cong, attacking nearby American and South Vietnamese forces, either accidentally or intentionally set fire to the nearby fishing village of Sontra along the South China Sea, killing eighty-eight civilians and wounding more than one hundred. In the United States on the same day, David Dellinger, head of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, said that one hundred organizations were working together to organize a series of demonstrations urging an end to the war, all scheduled to take place in Chicago that summer during the Democratic National Convention. On August 8 American forces on nighttime river patrol in the Mekong Delta, attempting to fight the Viet Cong with flamethrowers, killed seventy-two civilians from the village of Cairang, which had been friendly to American forces.

A new generation of Spaniards, after submitting passively to decades of Franco’s brutality, was beginning to confront the violent regime with violence. In 1952 five young Basques, dissatisfied with the passivity of their parents’ generation, formed an organization later called

Euskadi Ta Askatasuna,

which in their ancient language meant “Basqueland and Liberty.” Until 1968, the activities of the organization, known as ETA, consisted primarily of promoting the Basque language, which had been banned by Franco. Later, ETA members began burning Spanish flags and defacing Spanish monuments. In 1968 Basque linguists created a unified language in place of eight dialects. An example of the linguistic difficulties prior to 1968: The original name for ETA used the word

Aberri

instead of

Euskadi,

so that the acronym was ATA. But after six years of clandestine operations as ATA, they discovered that in some dialects, their name,

ata,

means “duck,” so the name was changed to ETA. The unified language of 1968 cleared the way for a renaissance of the Basque language.

But in 1968 ETA became violent. On June 7 a Civil Guard stopped a car that had two armed ETA members in it. They opened fire and killed the guard. One of the ETA killers, Txabi Etxebarrieta, was then tracked down and killed by the Spanish. On August 2, in revenge for the killing of Etxebarrieta, a much disliked San Sebastian police captain was shot dead by ETA in front of his home with his wife listening on the other side of the door. In response to the attack, the Spanish virtually declared war on the Basques. A state of siege was established that lasted for most of the rest of the year, with thousands arrested and tortured and some sentenced to years in prison, despite angry protests from Europe. Worse, a pattern of action and reaction, violence for violence, between ETA and the Spanish was established and has remained to this day.

In the Caribbean nation of Haiti it was the eleventh year of rule by François Duvalier, the little country doctor, friend of the poor black man, who had become a mass murderer. In a midyear press conference he lectured American journalists, “I hope the evolution of democracy you’ve observed in Haiti will be an example for the people of the world, in particular in the United States, in relation to the civil and political rights of Negroes.”

But there were no rights for Negroes or anyone else under the rule of the sly but mad Dr. Duvalier. One of the cruelest and most brutal dictatorships in the world, Duvalier’s government had driven so many middle- and upper-class Haitians into exile that there were more Haitian doctors in Canada than in Haiti. On May 20, 1968, the eighth coup d’état attempt against Dr. Duvalier began with a B-25 flying over the capital, Port-au-Prince, and dropping an explosive, which blew one more hole in an eroded road. Then a package of leaflets was dropped, which did not scatter because the invaders had not untied the bundle before dropping it. Then another explosive was dropped in the direction of the gleaming white National Palace, but it failed to explode. Port-au-Prince supposedly thus secured, the invasion began in the northern city of Cap Haïtien, where a Cessna landed with men opening tommy-gun fire at the unmanned control tower. The invaders were quickly killed or captured by Haitian army troops. On August 7 the ten surviving invaders were sentenced to death.

Walter Laqueur, a Brandeis historian who had written several books on the Middle East, wrote an article in May arguing that the region was potentially more dangerous than Vietnam. Later in the year Nixon would make the same point in his campaign speeches. What frightened the world about the Middle East was that the two superpowers had chosen sides and there was an obvious risk that the regional conflict would become a global one. The Israelis and the Arabs were in an arms race, with the Arabs buying Soviet weapons and Israelis buying American, while the Israelis, whose allies were not supplying them as quickly as the Soviets were the Arabs, also built up a homegrown arms industry.

“Gradually,” Laqueur wrote, “the world has reconciled itself to the fact that there will be a fourth Arab-Israeli War in the near future.” In July a poll showed that 62 percent of Americans expected another Arab-Israeli war within five years. The Egyptian government insisted on referring to its complete military rout in the Six Day War as the “setback.” Israel’s plan to offer the land it had seized in that war in exchange for peace was not working. There was a great deal of interest in land, but not in peace. The president of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, refused even to enter into negotiations with Israel. Mohammed Heykal, an Egyptian spokesman, insisted that another war was “inevitable”—perhaps because demonstrating Egyptian students were furious about the Egyptian performance in the last war. While the age of student movements had given birth to antiwar protests on campuses all over the world, Cairo students were protesting that their war hadn’t been fought well enough. Because Saudi Arabia considered itself a religious state, King Faisal was calling for a “holy war,” whereas Syria, considering itself to be a socialist state, had opted to call for a “people’s war.” The Palestinian organizations staged murderous little raids known as “terrorist attacks,” and the Israelis responded with massive firepower, often making incursions into Jordan.

The Arabs all agreed not to talk to the Israelis, because this would give the Israeli seizures some form of recognition. However, according to Laqueur, some were beginning to think they had made a mistake, since “in negotiation, the Zionists would have settled for much less than they eventually got.” A poll conducted in France showed that 49 percent of the French thought Israel should keep all or part of the new territories it gained in the 1967 war. Only 19 percent thought it should give it all back. The same poll conducted in Great Britain showed 66 percent thought Israel should keep at least some of the new territory and only 13 percent thought it should give it all back.

That land was the reason observers were giving as long as five years until the next war. If the Arabs had taken a beating in 1967, the next time would be even worse, now that the Israelis controlled the high ground at the Suez and the Golan. Many were already predicting Nasser’s overthrow from the last failure. But this situation subtly created a shift in the Middle East that was not clearly seen at the time. In the Arab world, the new policy was called “neither peace nor war.” Its aim was to wear down the Israelis. If the big armies were no longer in a position to lead conventional warfare, the alternative was small terrorist operations, which meant the Palestinians. Originally, such raids by Palestinians had been an Egyptian idea, sponsored by Nasser in the 1950s. The attacks were inexpensive and popular with the Arab public. Syria started sponsoring them in the mid-1960s. Now hundreds of guerrilla fighters were being trained in Jordan and Syria. This would greatly strengthen the hand of Palestinian leaders and facilitate the evolution of the “Arabs of occupied Jordan” into “the Palestinian people.” The Arab nations, especially Syria, were scrambling to assert control over these guerrilla organizations. But by the summer of 1968 Al Fatah had established itself as a separate power in Jordan beyond King Hussein’s control. The group had come a long way from its first operation—a disastrous attempt to blow up a water pump—only four years earlier.

Before the 1967 war, the Israelis refused to describe any of their actions as either a “reprisal” or a “retaliation.” Government censors would even cut these two words from correspondents’ dispatches. But by 1968 both of these terms were in common usage as Israelis struck beyond Jordan’s and Lebanon’s borders to reach the Palestinian guerrillas.

By summer, with the Israeli government having given the concept of land for peace a year’s effort, Israelis, if not their government, were giving up and settling in to Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, into a larger and different Israel from the one they had dreamed of. Amnon Rubenstein of the Tel Aviv daily

Ha’aretz

wrote, “The Israelis, on the other hand, will have to learn the art of living in an indefinite state of non-peace.”

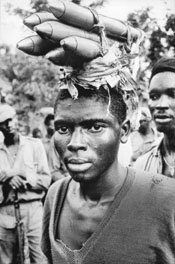

In the tropical, oil-rich delta of the Niger River, it was not nonpeace but open warfare that people were living with indefinitely. An estimated fifty thousand people had already died in combat. In May, when Nigerian troops took and destroyed the once prosperous city of Port Harcourt and put up a naval blockade and encircled Biafra with eighty-five thousand soldiers, the rebel Biafrans lost all connection to the outside world. It was reported that the Nigerian force had massacred several hundred wounded Biafran soldiers in two hospitals. The small breakaway state that did not want to be part of Nigeria was fighting on with an army of twenty-five thousand against the one-hundred-thousand-soldier Nigerian army. It had no heavy weaponry, a shortage of ammunition, and not even enough hand weapons to arm each soldier. The Nigerian air force with Soviet planes and Egyptian pilots bombed and strafed towns and villages, leaving them littered with corpses and writhing wounded. The Biafrans said that the Nigerians, whom they usually referred to by the name of the dominant tribe, the Hausa, intended to carry out genocide and that they specifically targeted schools, hospitals, and churches in their air attacks. But what finally started to get the world’s attention after a year of fighting was the shortage not of weapons but of food.

Biafran soldier in 1968

(Photo by Don McCullin/Magnum Photos)

Pictures of skeletal children staring with sad, unnaturally large eyes—children who looked unlikely to live through the week—began showing up in newspapers and magazines all over the world. The pictures ran in news articles and in advertisements that were desperate pleas for help. But most attempts at help were not getting through. The Biafrans maintained a secret and dangerous airstrip—a narrow, cleared path lit with kerosene lamps to receive the few relief planes. Those who attempted to find this strip had to first fly through a zone of radar-guided Nigerian antiaircraft fire.

The West learned a new word, “kwashiorkor,” the fatal lack of protein from which thousands of children were dying. Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Umuahia had treated 18 cases of kwashiorkor in all of 1963, but, visited by reporters in August 1968, the same hospital was treating 1,800 cases a day. It was estimated that between 1,500 and 40,000 Biafrans were dying of starvation every week. Even those who managed to get to refugee camps often starved. What food there was had become unaffordable. A chicken worth 70 cents in 1967 cost $5.50 in 1968. People were being advised to eat rats, dogs, lizards, and white ants for protein. Hospitals filled with children who had no food, medicine, or doctors. The small, bony bodies rested on straw mats; as they died they were wrapped in the mats and placed in a hole. Every night the holes were covered and a new one dug for the next day.