1989 - Seeing Voices (15 page)

Read 1989 - Seeing Voices Online

Authors: Oliver Sacks

Bellugi has, above all, studied the morphological processes of ASL—the ways in which a sign is changed to express different meanings through grammar and syntax. It was evident that the bare lexicon of the

Dictionary of American Sign

was only a first step—for a language is not just a lexicon or code. (Indian sign language, so-called, is a mere code—i.e., a collection or vocabulary of signs, the signs themselves having no internal structure and scarcely capable of being modified grammatically.) A genuine language is continually modulated by grammatical and syntactic devices of all sorts. There is an extraordinary richness of such devices in ASL, which serve to amplify the basic vocabulary hugely.

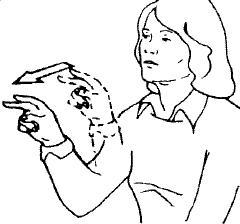

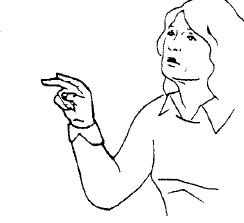

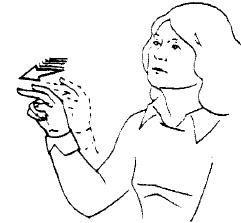

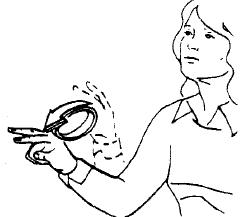

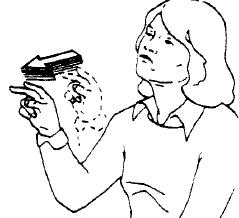

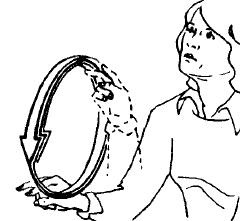

Thus there are numerous forms of LOOK-AT (‘look-at-me,’ ‘look-at-her,’ ‘look-at-each-of-them,’ etc.), all of which are formed in distinctive ways: for example, the sign LOOK AT is made with one hand moving away from the signer; but when inflected to mean ‘look at each other’ is made with both hands moving towards each other simultaneously. A remarkable number of inflections are available to denote durational aspects (fig. 1); thus LOOK-AT (a) may be inflected to mean ‘stare’ (b), ‘look at incessantly’ (c), ‘gaze’ (d), ‘watch’ (e), ‘look for a long time’ (f), or ‘look again and again’ (g)-and many other permutations, including combinations of the above. Then there are large numbers of derivational forms, the sign LOOK being varied in specific ways to mean ‘reminisce,’ ‘sightsee,’ ‘look forward to,’ ‘prophesy,’ ‘predict,’ ‘anticipate,’ ‘look around aimlessly,’ ‘browse,’ etc.

LOOK AT

LOOK AT

STARE

STARE

LOOK AT INCESSANTLY

LOOK AT INCESSANTLY

GAZE

GAZE

WATCH

WATCH

(f) LOOK FOR A LONG TIME

(f) LOOK FOR A LONG TIME

(g) LOOK AGAIN AND AGAIN

(g) LOOK AGAIN AND AGAIN

Figure

1. The root sign LOOK-AT may be modified in many ways. These are some of the inflections for the temporal aspects of LOOK-AT; there are many others, for distinctions of degree, manner, number, etc. (Reprinted by permission [with change in notation] from

The Signs of Language

, E.S. Klima & U. Bellugi. Harvard University Press, 1979.)

The face may also serve special, linguistic functions in Sign: thus (as Corina, Liddell, and others have shown) specific facial expressions, or, rather ‘behaviors,’ may serve to mark syntactic constructions such as topics, relative clauses, and questions, or function as adverbs or quantifiers.

90

90. See Carina, 1989.

Other parts of the body may also be involved. Any or all of this—this vast range of actual or potential inflections, spatial and kinetic—can converge upon the root signs, fuse with them, and modify them, compacting an enormous amount of information into the resulting signs.

It is the

compression

of these sign units, and the fact that all their modifications are

spatial

, that makes Sign, at the obvious and visible level, completely unlike any spoken language, and which, in part, prevented it from being seen as a language at all. But it is precisely this, along with its unique spatial syntax and grammar, which marks Sign as a true language—albeit a completely novel one, out of the evolutionary mainstream of all spoken languages, a unique evolutionary alternative. (And, in away, a completely surprising one, considering we have become specialized for speech in the last half million or two million years. The potentials for language are in us all—this is easy to understand. But that the potentials are a

visual

language mode should also be so great—this is astonishing, and would hardly be anticipated if visual language did not actually occur. But, equally, it might be said that making signs and gestures, albeit without complex linguistic structure, goes back to our remote, pre-human past—and that speech is really the evolutionary newcomer; a highly successful newcomer which could replace the hands, freeing them for other, non-communicational purposes. Perhaps, indeed, there have been two parallel evolutionary streams for spoken and signed forms of language: this is suggested by the work of certain anthropologists, who have shown the co-existence of spoken and signed languages in some primitive tribes.

91

91. See Levy-Bruhl, 1966.

Thus the deaf, and their language, show us not only the plasticity but the latent potentials of the nervous system.)

The single most remarkable feature of Sign—that which distinguishes it from all other languages and mental activities—is its unique linguistic use of space.

92

The complexity of this linguistic space is quite overwhelming for the ‘normal’ eye, which cannot see, let alone understand, the sheer intricacy of its spatial patterns.

92. Since most research on Sign at present takes place in the United States, most of the findings relate to American Sign Language, although others (Danish, Chinese, Russian, British) are also being investigated. But there is no reason to suppose these are peculiar to ASL—they probably apply to the entire class of visuo-spatial languages.

We see then, in Sign, at every level—lexical, grammatical, syntactic—a

linguistic

use of space: a use that is amazingly complex, for much of what occurs linearly, sequentially, temporally in speech, becomes simultaneous, concurrent, multileveled in Sign. The ‘surface’ of Sign may appear simple to the eye, like that of gesture or mime, but one soon finds that this is an illusion, and what looks so simple is extraordinarily complex and consists of innumerable spatial patterns nested, three-dimensionally, in each other.

93

93. As one learns Sign, or as the eye becomes attuned to it, it is seen to be fundamentally different in character from gesture, and is no longer to be confused with it for a moment. I found the distinction particularly striking on a recent visit to Italy, for Italian gesture (as everyone knows) is large and exuberant and operatic, whereas Italian Sign is strictly constrained within a conventional signing space, and strictly constrained by all the lexical and grammatical rules of a signed language, and not in the least ‘Italianate’ in quality: the difference between the para-language of gesture and the actual language of Sign is evident here, instantly, to the untutored eye.

The marvel of this spatial grammar, of the linguistic use of space, engrossed Sign researchers in the 1970’s, and it is only in the present decade that equal attention has been paid to time. Although it was recognized earlier that there was sequential organization within signs, this was regarded as phonologically unimportant, basically because it could not be ‘read.’ It has required the insights of a new generation of linguists—linguists who are themselves often deaf, or native users of Sign, who can analyze its refinements from their own experience of it, from ‘within’—to bring out the importance of such sequences within (and between) signs. The Supalla brothers, Ted and Sam, among others have been pioneers here. Thus, in a groundbreaking 1978 paper, Ted Supalla and Elissa Newport demonstrated that very finely detailed differences in movement could distinguish some nouns from related verbs: it had been thought earlier (for example, by Stokoe) that there was a single sign for ‘sit’ and ‘chair’—but Supalla and Newport showed the signs for these were subtly but crucially separate.

94