26 Fairmount Avenue (5 page)

Read 26 Fairmount Avenue Online

Authors: Tomie dePaola

But before the plasterers came, Mr. Johnny Papallo gave me a piece of bright blue chalk from his toolbox. He knew I wanted to be an artist when I grew up. I looked at those blank walls and knew what I wanted to do.

I asked my mom if I could make drawings of the family on the walls. She and my dad talked about it, and finally my dad said, “Okay, Tomie. Mom and I decided that you can make pictures on the plasterboard. But as soon as the plasterers come, no more drawing on the walls. Okay?”

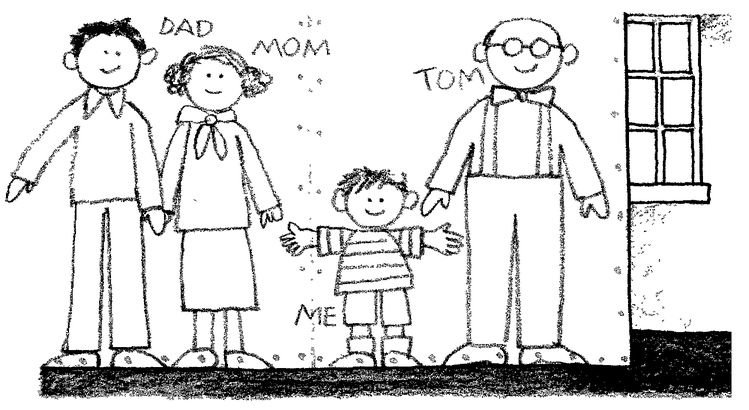

Sure, it was okay. But maybe if they saw how great my pictures were, they'd keep them. I decided I would give each person in the family a special corner in what was going to be our living room.

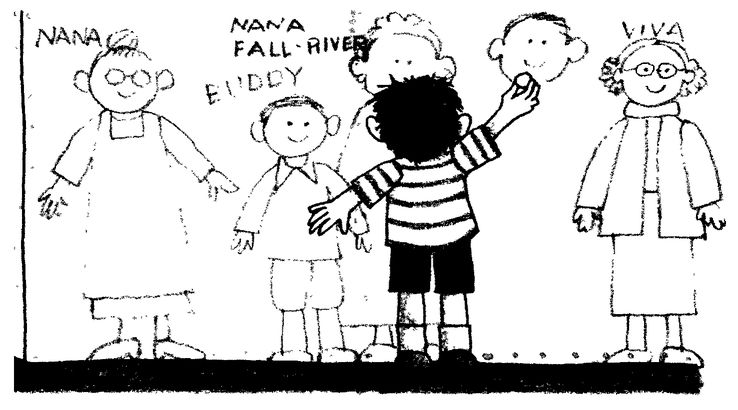

I put Mom and Dad in a corner by the fireplace. I put my grandfather, Tom, in the other corner. (I put me there, too.) I put Buddy and Nana Downstairs and Nana Fall River by the kitchen. That way they wouldn't have far to go. (I didn't draw Nana Upstairs because she had died and gone to heaven a few months before.) The corner by the front door was for Uncle Charles and his girlfriend, Viva. Along the wall I drew some cousins, looking out the two windows.

We didn't have real stairs to the second floor yet, so I couldn't go up to the bedrooms. Mom had already told me that the biggest one was for her and Dad, and the smallest one was the just-in-case nursery. (Later we needed it for my sisters, Maureen and Judie.)

If I could have gotten up there I would have gone into the room Buddy and I were going to share and marked which side was mine. But that would have to wait.

The plasterers finally came and covered over all my beautiful drawings. I was mad about that, but my grandfather, Tom, told me that was perfect because they'd always be there under the plaster and wallpaper. That made me feel better. Tom always made me feel better.

With everything moving along smoothly, my dad started talking about the “backyard project.” The backyard was filled with weeds and tall grass and stuff. It would be plowed and smoothed so grass could be planted.

“I'm going to wait for fall to get here for the backyard project,” Dad said. “Maybe we can start on the front wall and the steps up to the walkway to the front door.”

But before they did, guess what? The City came back and scraped more and more dirt away from the street. Our house was even higher up in the air than before, and we needed the wall more than ever.

My mom kept crying. My dad kept using more and more bad words.

Chapter Five

I

n the fall of 1939, almost one year after the Hurricane of 1938, I started school. I was hoping that I could say my address was 26 Fairmount Avenue, but not yet.

n the fall of 1939, almost one year after the Hurricane of 1938, I started school. I was hoping that I could say my address was 26 Fairmount Avenue, but not yet.

I was excited about going to school because I knew that in school you learned to read. I really wanted to learn so that I wouldn't always have to wait for my mom to read stories to me.

The first day of school came. I was going to be in the afternoon kindergarten class. My mom and I walked to King Street. At the corner, I said, “I know the way,” (it was just down the street). “I want to go alone.” My mom said I could. She watched me walk down the street. She waved when I reached the school.

I walked up the long front stairs where the boy with the umbrella had floated down during the hurricane. I didn't know that students weren't supposed to use those stairs. They were reserved for the president or the king of England and especially for the superintendent of schools.

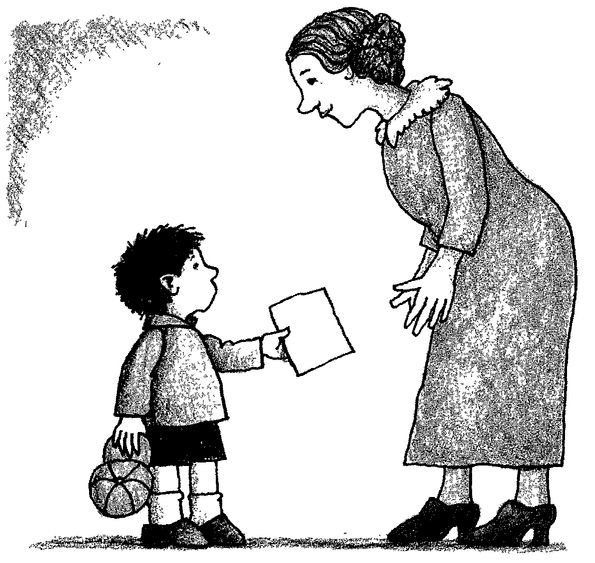

I pulled open the heavy front door and went in. A lady was standing there. “Who are you, little boy?” she asked.

“I'm Tomie dePaola,” I answered. “Who are you?”

“I'm Miss Burke, the principal.” (I got to know her really well over the next seven years.)

Miss Burke told me not to use the front door again, and she showed me where the kindergarten room was.

The room was filled with kids crying and hanging onto their mothers. Boy, I thought, what babies. I didn't realize that I would be in school with those kids for years and years.

I went up to a lady who looked like she might be the teacher. She was.

“And who are we?” she asked. (She always used “we.” “We must take our naps now,” or “We must bring our chairs into a circle”âstuff like that.)

“I'm Tomie dePaola,” I said.

“Oh, aren't we lucky,” she said. “I had your big brother, Joseph, in kindergarten, too,” (she was talking about Buddy). Well, I figured it wouldn't take too long for her to realize that my brother and I were very different. But that could wait.

“When do we learn how to read?” I asked.

“Oh, we don't learn how to read in kindergarten. We learn to read next year, in first grade.”

“Fine,” I said. “I'll be back next year.” And I walked right out of the school and all the way home.

No one was there. My dad was working at the barbershop, and my mom was off shopping all by herself for the first time in a long while.

The school called my dad at the barbershop. He found my mom, and they came roaring home to Columbus Avenue.

There I was, holding one of my mom's big books, staring at it, hoping that I could learn to read by myself.

Other books

Tony Dunbar - Tubby Dubonnet 07 - Tubby Meets Katrina by Tony Dunbar

The Judge by Steve Martini

The Swamp Boggles by Linda Chapman

Galatea by Madeline Miller

The Story of Evil: Volume I - Heroes of the Siege by Tony Johnson

The Sober Truth by Lance Dodes

Out to Canaan by Jan Karon

A Surprise for Lily by Mary Ann Kinsinger

Coach: Lessons on the Game of Life by Lewis, Michael

The Shattered Helmet by Franklin W. Dixon