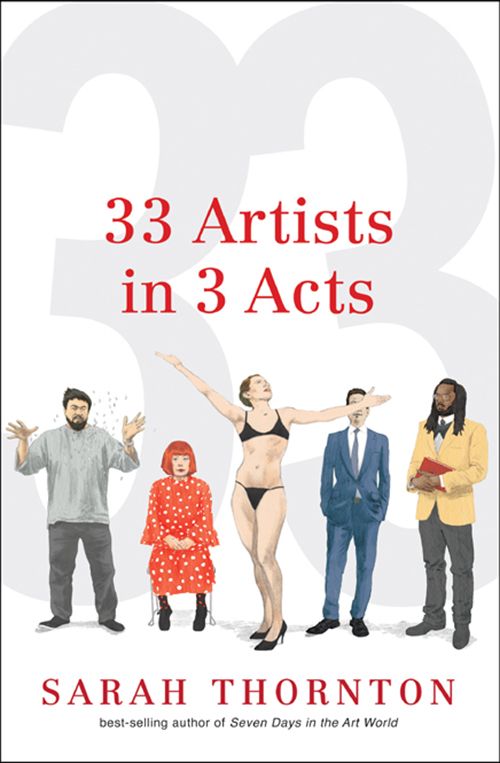

33 Artists in 3 Acts

33 Artists in 3 Acts

SARAH THORNTON

W. W. Norton & Company

NEW YORK • LONDON

FOR OTTO AND CORA

CONTENTS

Gabriel Orozco

Horses Running Endlessly

1995

“I don’t believe in art. I believe in the artist.”

—MARCEL D

UCHAMP

A

rtists don’t just make art. They create and preserve myths that give their work clout. While nineteenth-century painters faced credibility issues, Marcel Duchamp, the grandfather of contemporary art, made belief a central artistic concern. In 1917, he declared that an upended urinal was an artwork titled

Fountain

. In doing so, he claimed a godlike power for all artists to designate anything they chose as art. Maintaining this kind of authority is not easy, but it is now essential for artists who want to succeed. In a sphere where anything can be art, there is no objective measurement of quality, so ambitious artists must establish their own standards of excellence. Generating such standards requires not only immense self-confidence, but the conviction of others. Like competing deities, artists today need to perform in ways that yield a faithful following.

Ironically, being an artist is a craft. When he rejected the handmade in favor of the “readymade,” Duchamp began crafting identities as well as ideas. He played with his persona in a range of works, presenting himself in drag as a character named Rrose Sélavy and as a confidence man or con artist. Like the size and composition of a work, the walk

and talk of an artist has to persuade, not just others but the performers themselves. Whether they have colorful, large-scale personas or minimal, low-key selves, believable artists are always protagonists, never secondary characters who inhabit stereotypes. For this reason, I see artists’ studios as private stages for the daily rehearsal of self-belief. It’s one of the reasons that I chose to divide

33 Artists

into three “acts.”

This book explores the nature of being a professional artist today. It investigates how artists move through the world and explain themselves. Over the course of four years and several hundred thousand air miles, I interviewed 130 artists. Some famous artists and many thoughtful, interesting ones have been left on the cutting-room floor. My criteria resembled those of both a curator and a casting director. In other words, the artists’ work had to be relevant but their characters also had to engage. Occasionally, an interview felt like an audition. I remember asking an eminent photographer, who has always insisted on being called an artist, the driving question of my research: “What is an artist?” He replied, “An artist makes art.” I felt like shouting “Next!” as if a queue of prospective artist-characters stood waiting in the wings. His circular reasoning implied a fruitless line of inquiry. It demonstrated that, while the art world is ostensibly all for “dialogue,” it will shun awkward questions and cling to bewilderment when that is opportune.

33 Artists in 3 Acts

is biased toward artists who are open, articulate, and honest—which is not to say that disingenuousness is completely absent from these pages. On the contrary, I include suspicious statements for contrast and comic relief. Sometimes I question the utterances; other times I let them slide. I want the reader to be the judge. After reading this book in manuscript form, Gabriel Orozco, the only artist who appears in two separate acts, said, “We are all portrayed in our underwear. At least some of us get to keep our socks on.”

The artists in this book hail from fourteen countries on five continents. Most were born in the 1950s and 1960s. In the interest of exploring some of the variation within the expanding field, I consider artists who position themselves at diverse points along the following spectrums: entertainer versus academic, materialist versus idealist, narcissist versus altruist, loner versus collaborator. Although most of the artists have

attained high degrees of recognition somewhere in the world, each act contains a scene with an artist who teaches and, like the majority of artists, doesn’t make a living through sales of their work.

The themes that govern the book’s three acts were a key influence on my choices. Politics, kinship, and craft are rubrics that you might find shaping a classic anthropological tome. They are not typical of art criticism or art history, but, through research, I discovered that they demarcate the ideological border that differentiates artists from non-artists, or “real artists” from unimpressive ones. Politics, kinship, and craft also happen to embrace some of the most important things in life: caring about your influence on the world, connecting meaningfully with others, and working hard to create something worthwhile. “Act I: Politics” explores artists’ ethics, their attitudes to power and responsibility, paying particular attention to human rights and freedom of speech. “Act II: Kinship” investigates artists’ relationships with their peers, muses, and supporters with an eye on competition, collaboration, and ultimately love. “Act III: Craft” is about artists’ skills and all aspects of making artworks from conception through execution to market strategies. Needless to say, an artist’s “work” is not the isolated object, but the entire way they play their game.

33 Artists in 3 Acts

is also unconventional insofar as it insists on comparing and contrasting artists. Most of the literature on artists focuses on them individually in discrete monographs, or, when several artists are dealt with in one volume, they are segregated into disconnected profiles. Even when group shows throw artists together in interesting ways, the protocol for catalogue essays is to compare the works, not their makers. Indeed, the art world likes nothing better than to isolate a “genius.”

Each act of this book revolves around recurring characters who function as foils for one another. Act I casts Ai Weiwei in opposition to Jeff Koons, while Act III pitches the performance artist Andrea Fraser against Damien Hirst. In between, the kinship theme gives rise to clusters rather than pairs. Act II features an entire nuclear family: Laurie Simmons (a photographer) and Carroll Dunham (a painter) and their two daughters, Lena (the writer-director-star of the television show

Girls

)

and Grace (an undergraduate at Brown). Their scenes are juxtaposed with those of Maurizio Cattelan, a Duchampian bachelor, and his brothers-in-crime, curators Francesco Bonami and Massimiliano Gioni. These, in turn, are put into perspective by a couple of encounters with Cindy Sherman, who once described Simmons as her “artist soul mate.”

Just as my previous book

Seven Days in the Art World

chronicled the years 2004–07, so

33 Artists in 3 Acts

offers a snapshot of the recent past. All three acts open in summer 2009 and flow chronologically toward the time of writing (2013). The status of artists has changed markedly in the last few decades. No longer typified as impoverished struggling outcasts, artists have become models of unrivaled creativity for fashion designers, pop stars, and even chefs. In their ability to make markets for their work and ideas, they inspire entrepreneurs, innovators, and leaders of all kinds. Indeed, being an artist is not just a job but an identity dependent on a broad range of extracurricular intelligences.

33 Artists in 3 Acts

aims to give its readers a vivid and textured understanding of a group of professionals who are increasingly positioned by the wider world as ultimate individuals with enviable freedoms. A few art-world friends initially tried to convince me that artists are so unique that it would be misguided—not to mention disrespectful—to define them or write about them as a group. But I’m confident that, by the time readers reach the last page, they will have a strong sense of the many parallels to be found between artists currently perceived as unparalleled.

Jeff Koons

Made in Heaven

1989

O

n a sweltering July evening in 2009, Jeff Koons walks onto the stage of a packed auditorium at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The crowd, which is evenly split between art students in ironic T-shirts and retirees in comfortable shoes, gives him a loud round of applause. Clean-shaven with a gentle tan, the artist is wearing a buttoned-up black Gucci suit with a white shirt and dark tie. Twenty years ago, Koons thwarted the expectations of the New York art world by showing up in tailored suits when jeans and leather jackets were the norm. Artists didn’t have a uniform but there was one rule: don’t look like a businessman.

“It is really an honor to be here,” says Koons into a bulbous microphone. “Last year, I had an exhibition at Versailles and shows at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.” Artists’ talks are often a pitch for recognition; itemizing recent CV highlights is not unusual. “After such a lineup, the Serpentine is the most perfect location. It has been a thrilling experience. I am very grateful,” he proclaims like a rock star who has something nice to say about every stop on a concert tour.

*