44 Scotland Street (34 page)

Read 44 Scotland Street Online

Authors: Alexander McCall Smith

Tags: #Mystery, #Adult, #Contemporary, #Humour

82. On the Way to Mr Rankin’s

Ian Rankin! This revelation took Matthew and Pat by surprise, but at least they now knew where the painting had gone and whom they would have to approach in order to get it back. Once the name had been established, the third woman in the shop was able to tell them where Ian Rankin lived – not far away – and they prepared to leave. But Pat hesitated.

“That painting,” she enquired, pointing at the window display. “Would you mind if I looked at it?”

Priscilla went forward to extract the painting from its position in the window and passed it to Pat. “It’s been there for rather a long time,” she said, fingering her pearl necklace as she spoke. “It was brought in with a whole lot of things from a house in Craiglea Drive. Somebody cleared out their attic and brought the stuff in to us. I rather like it, don’t you? That must be Mull, mustn’t it? Or is it Iona? It’s so hard to tell.”

Pat held the painting out in front of her and gazed at it. It was in a rather ornate gilded frame, although this was chipped in several places and had a large chunk of wood missing from the bottom right-hand corner. The colours were strong, and there was something decisive and rather skilful about the composition. She looked for a signature – there was nothing – and there was nothing, too, on the back of the frame.

“How much are you asking for this?”

Priscilla smiled at her. “Not very much. Ten pounds? Would that be about right? Could you manage that? We could maybe make it a tiny bit cheaper, but not much.”

Pat reached into the pocket of her jeans and extracted a twenty pound note, which she handed over to Priscilla.

“Oh!” said the older woman. “Twenty pounds. Will we be able to change twenty pounds? I don’t know. What’s in the float, Dotty?”

“It doesn’t matter about the change,” said Pat quickly. “Treat it as a donation.”

“Bless you, you kind girl,” said Priscilla, beaming with approbation. “Here, let me wrap it up for you. And think what pleasure you’ll have in looking at that. Will you hang it in your bedroom?” She paused, and glanced at Matthew. Were they …? One never knew these days.

They took the wrapped-up painting and left the shop.

“What on earth possessed you to buy that?” Matthew asked, as they left. “That’s the sort of thing we throw out all the time. One wants to get rid of things like that, not buy them.”

Pat said nothing. She was satisfied with her purchase, and could imagine where she would hang it in her room in the flat. There was something peaceful about the painting – something resolved – which strongly appealed to her. It may be another amateur daubing, but it was comfortable, and quiet, and she liked it.

They crossed the road at Churchill and made their way by a back route towards the address they had been given.

“What are we going to say to him?” asked Matthew. “And what do you think he’ll say to us?”

“We’ll tell him exactly what happened,” said Pat. “Just as we told those people. And then we’ll ask him if he’ll give it back to us.”

“And he’ll say no,” said Matthew despondently. “The reason why he bought it in the first place is that he must have realised that it’s a Peploe?. Somebody like him wouldn’t just pop into a charity shop and buy any old painting. He’s way too cool for that.”

“But why do you think he knows anything about art?” asked Pat. “Isn’t music more his thing? Doesn’t he go on about hi-fi and rock music?”

Matthew shrugged. “I don’t know. It’s just that I’ve got that bad feeling again. This whole thing keeps giving me bad feelings. Maybe we should just forget about it.”

“You can’t,” said Pat. “That’s forty thousand pounds worth of painting. Or it could be. Can you afford to turn up your nose at forty thousand pounds?”

“Yes,” said Matthew. “I don’t actually have to make a profit in the gallery, you know. I’ve never had to make a profit in my life. My old man’s loaded.”

Pat was silent as she thought about this. She had been aware that Matthew did not have to operate according to the laws of real economics, but he had never been this frank about it.

Matthew stopped walking and fixed Pat with a stare. Again she noticed the flecks in his eyes.

“Are you surprised by that?” he said. “Do you think the less of me because I’ve got money?”

Pat shook her head. “No, why should I? Plenty of people have money in this town. It’s neither here nor there. Money just is.”

Matthew laughed. “No, it isn’t. Money changes everything. I know what people think about me. I know they think I’m useless and I would never have got anywhere, anywhere at all, if it weren’t for the fact that my father can buy me a job. That’s what he’s done, you know. He’s bought me every job I’ve had. I’ve never got a job, not one single job, on merit. How’s that for failure?”

Pat reached out to touch him on the shoulder, but he recoiled, and looked down. She felt acutely uncomfortable. Self-pity, as her father had explained to her, is the most unattractive of states, and it was true.

“All right,” she said. “You’re a failure. If that’s the way you feel about yourself.” She paused. Her candour had made him look up in surprise. Had her words hurt him? She thought that perhaps they had, but that might do some good.

They began to walk again, turning down a narrow street that would bring them out onto Colinton Road. A cat ran ahead of them, having appeared from beneath a parked car, and then shot off into a garden.

“Tell me something,” said Matthew. “Are you in love with

that boy you share with? That Bruce? Are you in love with him?”

Pat made an effort to conceal her surprise. “Why do you ask?” she said, her voice neutral. It had nothing to do with him, and she did not need to answer the question.

“Because if you aren’t in love with him, then I wondered if …”

Matthew stopped. They had reached the edge of Colinton Road and his voice was drowned by the sound of a passing car.

Pat thought quickly. “Yes,” she said. “I’m in love with him.”

It was a truthful answer, and, in the circumstances, an expedient one too.

83. But of Course

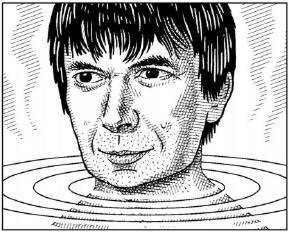

He was sitting in a whirlpool tub in the walled garden, wisps of steam rising from the water around him. A paperback book was perched on the edge of the tub, a red bookmark protruding from its middle.

“I find this a good place to think,” he said. “And you feel great afterwards.”

Matthew smiled nervously. “I hope you don’t mind us disturbing you like this,” he said. “We could come back later if you like.”

Ian Rankin shook his head. “Doesn’t matter. This is fine. As long as you don’t mind me staying in here.”

There was a silence for a few moments. Then Pat spoke. “You bought a painting this morning.”

A look of surprise came over Ian Rankin’s face. “So I did.” He paused. “Now, let me guess. Let me guess. You’ve heard all about it and you want to buy it off me? You’re dealers, right?”

“Well we are,” said Matthew. “In a way. But …”

Ian Rankin splashed idly at the water with an outstretched hand. “It’s not for sale, I’m afraid. I rather like it. Sorry.”

Matthew exchanged a despondent glance with Pat. It was just

as he had imagined. Ian Rankin had recognised the painting for what it was and was holding onto his bargain. And who could blame him for that?

Pat took a step forward and leaned over the edge of the tub. “Mr Rankin, there’s a story behind the painting. It’s my fault that it ended up in that shop. I was looking after it and my flatmate took it by mistake and gave it as a raffle prize and then …”

Ian Rankin stopped her. “So it’s still yours?”

“Mine,” said Matthew. “I have a gallery. She was looking after it for me.”

“What’s so special about it?” Ian Rankin asked. “Is it by somebody well known?”

Matthew looked at Pat. For a moment she thought he was going to say something, but he did not. So the decision is mine, she thought. Do I have to tell him what I think, or can I remain silent? She closed her eyes; the sound of the whirlpool was quite loud now, and there was a seagull mewing somewhere. A child shouted out somewhere in a neighbouring garden. And for a moment, inconsequentially, surprisingly, she thought of Bruce. He was smiling at her, enjoying her discomfort.

Lie

, he said.

Don’t be a fool

.

Lie

.

“I think that it may be by Samuel Peploe,” she said. “It looks very like his work. We haven’t taken a proper opinion yet, but that’s what we think.”

The corner of Matthew’s mouth turned down. She’s just destroyed our chances of getting it back, he thought. That’s it.

Ian Rankin raised an eyebrow. “Peploe?”

“Yes,” said Pat.

“In which case,” said Ian Rankin, “it’s worth a bob or two. What would you say? It’s quite small, and so … forty thousand? If it were bigger, then … eighty?”

“Exactly,” said Pat.

Ian Rankin looked at Matthew. “Would you agree with that?”

“I would,” said Matthew, adding glumly, “Not that I know much about it.”

“But you’re the dealer?”

“Yes,” said Matthew. “But there are dealers and dealers. I’m one of the latter.”

“I’m just going to have to think about this for a moment,” said Ian Rankin. “Give me a moment.”

And with that he took a deep breath and disappeared under the surface of the water. There were bubbles all about his head and the water seemed to take on a new turbulence.

Pat looked at Matthew. “I had to tell him,” she said. “I couldn’t lie. I just couldn’t.”

“I know,” said Matthew. “I wouldn’t have wanted you to lie.”

He wanted to say something else, but did not. He wanted to tell her that this was exactly what he liked about her, even admired – her self-evident honesty. And he wanted to add that he felt strongly for her, that he had come to appreciate her company, her presence, but he could not, because she was in love with somebody else – just as he had feared – and he did not expect, anyway, that she would want to hear this from him.

Ian Rankin seemed to be under the water for some time, but at last his head emerged, dark hair plastered over his forehead, the keen, intelligent eyes seeming brighter than before.

“It’s in the kitchen,” he said. “But of course you can have it back. Go inside and I’ll join you in a moment. I’ll get it for you.”

Matthew began to thank him, but he brushed the thanks aside, as if embarrassed, and they made their way into the house.

“I didn’t think he’d do that,” Matthew whispered. “Not after you said what it could be worth.”

“He’s a good man,” said Pat. “You can tell.”

Matthew knew that she was right. But it interested him nonetheless that a good man could write about the sort of things that he wrote about – murders, distress, human suffering: all the dark pathology of the human mind. What lay behind that? And if one thought of his readers – who were they? The previous year, on a trip to Rome, he had been waiting for a plane back to Edinburgh and had been queuing behind a group of young men. He had observed their clothing, their hair cuts, their demeanour, and had concluded – quite rightly as their conversation later revealed – that they were priests in training. They had about them that air that priests have – the otherworldliness, the fastidiousness of the celibate. Matthew judged from their accents that they were English, the vowels of somewhere north – Manchester perhaps.

“Will you go straight home?” asked one.

“Yes,” his friend replied. “Straight home. Back to ordinary parish liturgy.”

The other looked at the book he was holding. “Is that any good?”

“Ian Rankin. Very. I read everything he writes. I like a murder.”

And then they had passed on to something else – a snippet of gossip about the English College and a monsignor. And Matthew had thought: Why would a priest like to read about murder? Because good is dull, and evil more exciting? But was it? Perhaps the reason the good like to contemplate the deeds of the bad is that the good realise how easy it is to behave as the bad behave; so easy, so much a matter of chance, of fate, of what the philosophers call moral luck. But of course.

84. An Invitation

Immensely relieved at the recovery of the Peploe?, Matthew and Pat returned to the gallery in a taxi, the painting safely tucked away in a large plastic bag provided by Ian Rankin. Matthew’s earlier mood of self-pity had lifted: there were no further references to failure and Pat noticed that there was a jauntiness in the way he went up the gallery steps to unlock the door. Perhaps the recovery of a possible forty thousand pounds meant more to Matthew than he was prepared to admit, even if the identity of the painting was still far from being established. In fact all they knew – as Pat reminded herself – was that she thought that it might be a Peploe, and who was she to express a view on such a matter? Her pass in Higher Art – admittedly with an A – hardly qualified her to make such pronouncements, and she was concerned at having raised everybody’s hopes prematurely.