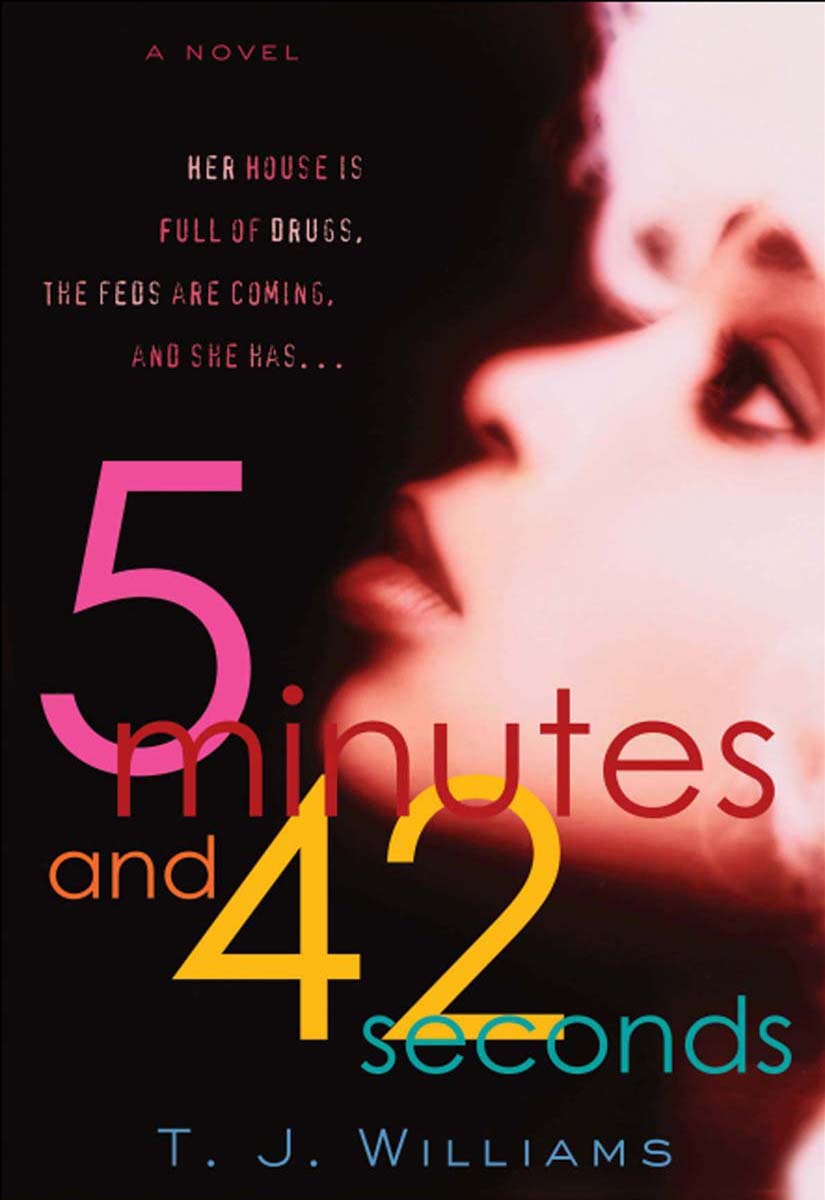

5 Minutes and 42 Seconds

Read 5 Minutes and 42 Seconds Online

Authors: Timothy Williams

T. J. Williams

From: twins.

To: you.

For: all of us.

I

nside a perfect house,

in a perfect neighborhood, on a well-paved street with mansions to either side, a trumpet sounds, and the procedure begins.

Cameisha Douglass stands at the bottom of the stairs, trumpet in hand. Her hair still wrapped in a sleeping bun, her face thick with the makeup she slept in just in case her philandering husband, Fashad, comes home for a change.

“Cold blue!” she screams, not realizing the proper term is

“code

blue.” Feet pitter-patter in the distance as the children move toward their designated stations. Her youngest children, Taj and JD, have both the most important and easiest task. When the trumpet sounds, they are to run to the bathroom, remove stockpiles of cocaine from beneath a panel in the floor, and flush their father's coke down the toilet. For now, they are flushing the flour Cameisha switched

with the real stuff earlier. The job is simple, the children young and impressionable.

With her daughter, Dream, things are more complicated. Dream doesn't bother getting up when she hears the signal. Cameisha barges into her daughter's room without knocking. Dream slightly removes the covers from her face revealing a round, full face, caked with makeup, imitative of the thinner mush of CoverGirl supporting her mother's much thinner features.

“If you don't get your black ass out that bed and do what your stepfather told you to do, I will beat the black off of it,” says Cameisha.

Dream rolls over, ignoring her. Cameisha grabs the covers and Dream tugs them backâCameisha gives her an impatient motherly stare. Dream lets go of the covers, then throws a fit, as if she is the youngest child in the household. Nevertheless, she gets up soon after.

Cameisha passes the bathroom where the boys, kneeling like altar boys, flush the cocaine. Ten seconds later she's back down the stairs, busy with her own task of removing clothes from the living room closet, thus making room for a trap door that is to be cut in the interior of the closet. By the time she removes the last garment, Dream has reluctantly mobilized and stands in the hallway with a chain saw, ready to cut. But before Dream gets started, Cameisha presents her with a wooden box. “Practice on this,” she says. “I ain't fuckin' up my closet for nothing.”

Dream rolls her eyes, then starts the chain saw. Taj and JD scurry about upstairs, shaking salt shakers to throw off the scent when the dogs come. Dream finishes cutting. The

four of them race to a television that isn't really a television and remove a huge sum of money from the hollow space inside, where wiring and electronics used to be. They rush and sweat as they transfer the cash from the TV to the safe. Quality time, the Douglass family way.

Cameisha checks her watch, stops the timer. “Five minutes and forty-two seconds,” she says. “That should be fast enough.”

H

ere come Fashad.

Six o'clock in the morning. I ain't seen this nigga for three days now, and he ain't wearin' the yellow hoodie and pinstriped Armani jacket he was wearin' when I saw him last. He's wearing a red leather jacket with white stripes and stonewashed jeans with a perfect crease in the middle. Fashad don't iron. I guess he ain't even trying to hide her from me no more. He come in rubbin' his stomach, talkin' 'bout “What you fix for dinner?”

I thought to myself,

No, this nigga did not just ask me about dinner after he ain't been here!

How he expect me to be a wife when he not a husband? You can't have one without the other. I ain't gonna lie. I get tired sometimes. But you can't go around changing thingsâit's been like this for a good five years now. I'm the commander, and he's the presi

dent. I do what I got to. Take what I gotta take. That's just the way it is. For now.

I took a look around my house before I said something I'd later regret. At least he comes home. He sure enough does support us.

Cameisha, do not go off,

I thought to myself. You got a good setup. So, instead, I answer, “It depends on what day you're asking about. Tuesday was spaghetti. Wednesday fried chicken and collard greens. I think we had McDonald's on Thursday. Friday I made lasagnaâused your mother's recipe. Yesterday I was tired. I guess you gonna have to eat somewhere else. Again.”

D

ream moped into the back

entrance of Bonzella's beauty shop thirty minutes late and half-asleep, hoping her first client was on CP time as well. Hearing gossipy voices she couldn't distinguish, she peered through the back door, hoping to slide through it as discreetly as possible. There was no chanceâthe salon was packed. First she saw Xander Thomas, her coworker, standing, at six feet and three inches, over a leather salon chair that couldn't have been more than five feet tall. His long hair came inches away from the back of the chair as he snipped away at his client Anastasia Dubois's nappy mane. Dream sneered when she saw herâAnastasia was a former classmate who gave her the nickname “Big Fat Cheese” because she was rich and overweight. Another coworker, Daryl, stood behind the chair in which his new client, Yolanda James, sat, flamboyantly playing with her well-kept

hair in front of the mirror. Two women sat in the waiting area. The first, Mavis Jones, was the resident busybody and neighborhood informant who never bothered to actually get her hair done. The second, unfortunately, was Leronda Jansen, Dream's eight o'clock.

“She betta come on. I got shit to do,” said Leronda pulling at an uninteresting permanent press that sat well with the old-schoolers at Olive Baptist, where her husband was due to make deacon anytime now.

“I don't see why y'all put up with her shit,” said Xander, smacking his glossed lips as he spoke while chopping at his client's hair, dramatically swishing his own to and fro.

“Nigga, please. You know why they do it,” said Daryl, finally taking a time-out from manipulating Yolanda's curly perm.

“'Cause she good,” said Leronda.

“Try again,” said Daryl, dropping the comb he held to his side and preparing to undertake his real job of gossip hound.

“You know they say she's crazy. That's why she don't talk.”

“Daryl, you need to stop,” said Xander.

They were all silent and Dream contemplated walking in then but thought better of it since not quite enough time had lapsed since they'd finished dragging her name through the mud. She knew they talked about her when she wasn't around but figured as long as she didn't confront them, they'd keep their comments behind her back, not throw them in her face the way the kids at school used to. High school was over and Dream wasn't about to revisit that type of pain and blatant disrespect. Walking into the salon at that moment might have caused a confrontation, so Dream stayed put.

“She might be crazy, but she can do some hair,” said Anastasia. “Seem like every girl I see walkin' down the street got her lil red, white, or blue somethin' or others in they hair. It ain't for me, but I don't judge. It must be right for a whole lot of other folks.”

“Shhhhhiiiiiitâ¦,” said Daryl, continuing to neglect Yolanda's hair. “Her having all these clients ain't got shit to do with that blue, green, purple Marge Simpson shit she be doing.”

“What it got to do with, then? Folks ain't coming in here for they health,” said Mavis Jones, peeking underneath the few strands of gray hair she was determined to make a bang from, the rasp in her voice thick enough to require a doctor's attention.

“It's got to do with this,” said Daryl putting the comb down and running toward the television. From her position behind the door, Dream couldn't make out what he was doing, but she heard the music from the commercial, and rolled her eyes.

All of Detroit had seen the commercial a million times. A trumpet sounds, announcing Fashad's arrival, as if he is some sort of dignitary. Fashad walks toward the camera through a cloud of blue smoke, clad in expensive garb from European designers with names no one in Detroit can properly pronounce. His strut is deliberate, the look in his eyes pretentious, as the spotlight engulfs him, barely illuminating two cars behind him. “Fashad knows quality,” says a woman in the background Dream couldn't identify but always thought to be her stepfather's mistress, a can of worms she dared not open.

“I'm Fashad Douglass, and I know quality. If you know quality, and prefer class to discount, then let me help you with all your auto needs. Why, you ask?” says Fashad, staring intently into the lens like a supermarket supermodel.

“Because⦔

“Fashad knows quality,” said Daryl right along with the commercial. Then he reappeared in Dream's line of sight and returned to Yolanda's curls.

“People don't come to Dream for Dream, they come to Dream for Fashad,” he continued.

“That's the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard,” said Xander. “Dream don't talk to nobody! If you coming to her to find out about Fashad you gonna be mighty disappointed.”

“You sound like you know from experience,” said Mavis.

Everyone laughs except Dream. Truth was, Xander had tried before, and he did find out the hard way that Dream didn't like to talk. It wasn't that she was mean, it wasn't that she was stuck up. She was just smart. What was the point of talking? People just said things they didn't mean, or said things they meant that hurt. Either way, Dream was afraid to listen. She kept her mouth shut, and hoped other people would pay her the same courtesy.

“These little fast bitches that come around here sniffing after her stepdaddy don't know she ain't givin' up no info!” said Daryl. “They see a fine-ass, rich motherfucker on the TV screen, and all they see is a way to get up out of Detroit. Now, they might not be going about going after Fashad the right way by coming to see Dream, but they most definitely going about it. You see how they be all buddy-buddy with her ugly ass.”

“That's not nice,” said Xander.

“I'm just telling the truth. She get on my nerves, acting like she can't talk to nobody. Wouldn't nobody want to talk to that ugly stuck-up bitch if it weren't for her daddy,” said Daryl.

“Well, she get it honest from her momma,” said Xander.

“Cameisha think her shit smell like daffodils.”

“You think she bad now, you should have known her in high school,” whispered Leronda, looking back to see if Dream was anywhere to be found. She got up from her chair to check the parking lot outside. She passed so close to where Dream was hiding behind the curtain her hair brushed Dream's face before she sat down and boldly continued her verbal bashing of Dream's mother. “Cameisha wasn't quiet, but she still didn't have any friends 'cause she couldn't stop talking about herself. All she talked about was how she knew this person and that person and how she was going to be a model, or she was going to be in somebody's video, or she was going to be in a movie, or had a record coming out. That bitch ain't have nothing coming out of her except for babies. She was pregnant with Dream before she could throw her graduation hat.”

“She is pretty, though,” said Daryl. “At least you got to give her that. Dream, on the other hand, look like a pregnant Wesley Snipes. And don't let me get started on that blue hair mess. At least Cameisha got that nice long pretty silky stuff.”

“That's all she got, though. I never did think she was pretty,” said Leronda.

“I know something else she got,” said Mavis.

“What?” asked Leronda. “Herpes? I heard that too.”

“She got Fashad. Seem to me you mad 'cause she got something you want.”

“No ma'am, I don't know what these young gals are up to in here with Dream, I just came to get a touch-up,” said Leronda.

“You could have gotten that touched up anywhere,” said Daryl. “Why you want her so badly? Especially when she always booked.”

“'Cause I like saying I go to her. Make me feel like I'm doing big thangs when, on Sunday, everybody else bragging about how she hooked them up.”

“See?” said Daryl, chastising her with his comb.

“See what?” she asked, demanding he explain his condescension. “Folks so stupid they think everything that got to do with Fashad is high-class, including his stepdaughter's hairstyles, and I can't be walking into church looking like anything. If they let me tell it, I say fuck Fashad. With his high-ass pricesâ¦That's why he don't be getting no business.”

“Well, I heard he don't want no business,” said Mavis.

“I heard he want business, and got more than anybody know. He just ain't sellin' no cars,” said Daryl.

“There y'all go again,” said Yolanda, who had been patiently waiting for the discussion to exit the realm of gossip so she could preach. “Why every time a black man get somewhere, or have something, y'all always got to say he slanging? Why can't he just be a legit businessman?”

“If he doing such good business, why doesn't anybody know about it? You ever heard of somebody that bought a car from Fashad?” asked Leronda like a prosecutor.

“No, but I don't know too many people here in Detroit. I just got here a couple months ago.”

“I know every nigga in this town, and they mommas and they daddies,” said Mavis, putting down her

Ebony

magazine and throwing one finger in the air to distinguish her decree, “and I ain't never heard of nobody getting no car from Fashad Douglass.”

“Well, how you know he ain't sellin' cars to white folks?” asked Xander.

“Yeah,” said Yolanda. “Why ya'll so ready to bring the brother down? Why y'all hatin'?”

“I'm not hatin', I'm just statin',” said Leronda. “These white folks around here don't want nothing that's passed through no black hands. His momma ain't have shit. His daddy was a gigolo and got more kids than Jerry. There ain't no other way for him to have all that money but by doing wrong.” She paused, but no one had anything to say, so she continued: “I hate to say it, but that's the way it is around here. It's gotten so bad these days that these young kids don't even think about being nothing else besides a rapper or a basketball player. When they little bubbles burst they got to turn to slanging. It's like if they can't rap, or play ball, then slanging is the only way for them to be something more than the broke-down good-for-nothing niggas that they are.”

“Don't say that,” said Yolanda, halfheartedly trying to defend the black men of Detroit.

“It's the truth,” said Leronda. “The ones that can really rap or play ball leave, so what that leave us with?”

“That leave us with a city full of ignorant, no-good, conniving niggers,” said Mavis.

“There are a lot of educated, chivalrous, fine black men in Detroit,” said Yolanda.

“Yeah, there are,” said Leronda.

“Thank you,” said Yolanda.

“And they all gay,” continued Leronda.

The room went into a chaos of laughter and refute. It was the perfect time for Dream to slide in as inconspicuously as possible. She heard what she heard, but it didn't change a thing. She didn't speak a sentence the entire day.