A Brief History of Creation (15 page)

Read A Brief History of Creation Online

Authors: Bill Mesler

I

N HIS LATER YEARS,

Andrew Crosse never mentioned his father's famous friends when retracing his own fascination with electricity. This omission was not surprising. Andrew Crosse was a progressive, but he was merely a proponent of reform, not a radical or revolutionary like his father had been. Andrew Crosse's outlet was the reformist Whig Party, and he even served a term as a member of Parliament representing Somerset County. With Richard Crosse's political views growing ever more marginalized as the years went by, it is not surprising that Andrew Crosse chose to steer clear of reference to Franklin and Priestley to avoid conjuring the specter of his father's radicalism.

Andrew Crosse received his first electric machines when he was sixteen,

the year his father died. Crosse was by that time devouring entire volumes of the

Philosophical Transactions

as soon as he could acquire them. He read whatever he could find on the subject of electricity. The bookseller at the shop Crosse frequented turned out to be an experimentalist himself and took an interest in the boy. He gave Crosse a crude generator that could produce energy from simple friction and a “battery table” that held thirty Leyden jars. Little more than a glass jar filled with water and containing a piece of metal foil to conduct electricity, the Leyden jar, named after the Dutch city where it was invented, was one of the earliest versions of an electric capacitor.

â¡

In time, Crosse would find a more efficient way to harness electricity from the atmosphere in the condensers and lightning rods he arranged in the trees outside his home. But the Leyden jar remained a staple in his laboratory. Eventually, his basement held three thousand of them.

That same year, workers in a nearby limestone quarry stumbled upon the entrance to a fantastic cave filled with aragonite crystals, which would come to be called Holwell Cavern. As a teenager, Crosse would spend hours sitting alone and watching the crystals glow in the dim flicker of candlelight, as if emanating some strange energy. He became convinced that their beauty was related to this mysterious force he was learning about, electricity. The crystals appeared to reach for each other, in mirror image, as if drawn together by an invisible force. Crosse guessed that the force was magnetic attraction.

Two years after Holwell Cavern's discovery, Crosse left for Brasenose College, Oxford. Crosse was a loner at heart and found his university years trying. Oxford, he wrote his mother, was “a perfect hell on earth.” Many years later, he would say that his years at Oxford had taught him that “ridicule is a terrible trial to the young.” He found solace in studying the Greek classics. Crosse always fancied himself a poet. He tended to wax on the beauty of nature, and Holwell Cavern became a favorite subject. In later years, his poetry frequently focused on his melancholia or the religious zealots who would turn on him at the end of his life.

When Crosse was twenty-one, his mother passed away, and he returned to Fyne Court. He found himself the master of a large estate with tenant farmers to manage. When it came to business, Crosse was a disaster. At some point, he was swindled out of much of his wealth, although he was rich enough that he never quite fell into a desperate state of affairs. As the years passed, he turned ever more eagerly to his electrical experiments, encouraged by the man who had by then become his closest friend, the electrical scientist George Singer.

When he was twenty-seven, Crosse devised his first electrical experiment, which he carried out at Holwell Cavern. He even began experimenting on local farmers who came to him with various ailments. It was said he could cure arthritis and even hangovers. Soon he was investigating all manner of possible uses for electric currents. Crosse's electrical investigations into the formation of crystals prompted a pilgrimage to Fyne Court by one of Britain's most celebrated scientists, Humphry Davy, president of the Royal Society. Davy had become a national hero in England after his invention of a lamp that could be used safely in methane-heavy coal mines. He was also a brilliant chemist who had used electricity to great effect in his chemical explorations, and his interest in Crosse's work stemmed from his own experiments. Using an electric current from a voltaic pile, Davy had discovered the process of electrolysis, enabling him to separate substances into their component chemical elements.

By 1836, interest in electricity was booming in England's scientific community, and Crosse was gaining in prestige, as well as in confidence. In the fall of that year, he traveled to Bristol to deliver a rare public address before the newly formed British Association for the Advancement of Science. His theories on the electrical formation of minerals were hailed as visionary and brought him enough notoriety that anyone involved in science knew who he was, as did many with no particular ties to science at all. By the time Crosse undertook his most famous experiment later that year, his scientific career was at its pinnacle.

Later, after events turned out very badly for Andrew Crosse, he would often protest that he was little more than the victim of unscrupulous newspapermen.

The truth is somewhere in between. While he did at first keep the discovery of his insects to himself, eventually he confided the story to the editor of a new local newspaper, the

Somerset Gazette

. He could hardly have been surprised that an enthusiastic story was published shortly thereafter.

On December 31, 1837, the first story about Crosse's fantastic insects appeared in the

Gazette

, under the title “An Extraordinary Experiment.” Eventually, the story reached London and the paper of record of the day, the

Times

. From there, news of the real “Dr. Frankenstein” went into syndication and spread like wildfire to all of the British Empire and beyond. Soon, newspapers were reportingâfalsely, it would turn outâthat Michael Faraday, the most famous electrical scientist of his time, had confirmed Crosse's results in his own laboratory. The press gave Crosse's insects a proper Latin species name. They called them

Acarus crossii

.

Crosse tried his best to remain aloof from the celebrity, and he distanced himself from any larger implications of what had happened in his organ-room lab. His subsequent experimental work continued to focus on finding a way to make crystals using electricity. His few follow-up attempts to understand how the insects appeared in his apparatus were fruitless.

One scientistâWilliam Weeks, a popular lecturer with a large public followingâclaimed to have replicated Crosse's experiment and found the same insects. But others who tried found nothing. The deeply religious Faraday, though sympathetic to Crosse, denied the reports that he himself had replicated the experiment. Faraday's protestations were virtually ignored in the press, which didn't want to diminish the sensational story, but in the scientific community, they were taken as just more evidence that the experiment was faulty. Crosse's story might have ended there.

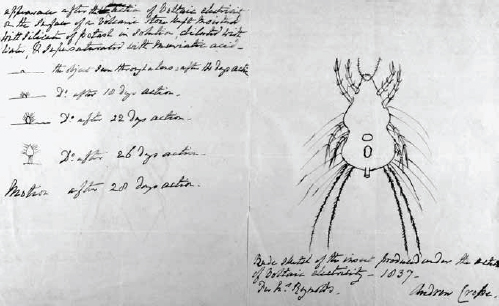

Crosse's diagram of what would be called

Acarus crossii

.

I

N 1844, CROSSE ONCE AGAIN

found himself in the public spotlight when a new anonymously authored work appeared on the shelves of England's booksellers. It was called

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

, and the British public had never seen anything like it. The novelist and future prime minister of England, Benjamin Disraeli, excitedly wrote his sister to tell her of the book that was “convulsing the world.” The first edition sold out within days.

Vestiges

was a naturalistic history of the universe, beginning with the creation of the stars and the heavens and running right up to the present time, fueled by what the unnamed writer called “the universal gestation of nature.” The history of life on Earth was traced to an original act of spontaneous generation, with Andrew Crosse's

Acarus crossii

held up as evidence. From this natural act of creation, Lamarckian transmutation became the engine for the creation of new species. In the original handwritten manuscript, next to the section on the origin of life, the author scrawled in the margin that the “great plot comes out here.”

In Victorian England, the book created a scandal, but the kind of scandal that made its publishers very rich. People rushed to get their hands on a copy. Prince Edward said he read it aloud to Queen Victoria every afternoon at tea. The fact that it was published anonymously only added to its appeal. Newspapers speculated endlessly about the identity of the mysterious author. Some said it was Andrew Crosse. Some said it was Erasmus Darwin's grandson, Charles. Still others suggested the author had to be a woman, many because they thought only a woman could pen such a

shoddy, ill-informed work. Maybe it was the radical political economist Harriet Martineau, they guessed, or Ada Lovelace, Lord Byron's daughter, writer of the first machine algorithm, which she had produced for mathematician Charles Babbage's never completed computational machine.

§

Not until after his death some thirty years later was the journalist and publisher Robert Chambers finally revealed to be the book's true author. Chambers went to great lengths to conceal his identity, even having his wife copy the original manuscript by hand, for fear his handwriting would be recognized by editors. He burned his notes and kept the manuscript in a locked drawer. Chambers was terrified of the inevitable religious backlash he would face if his identity was revealed. He and his brother owned a publishing house that earned most of its income from producing religious textbooks in their native Scotland. Discovery would have meant financial ruin.

Though Chambers was a religious skeptic, he went to great lengths in his book to insist that the process he described was, at its root, the work of a divine hand. Even the title was a concession. The content of the book still proved too much of a challenge to biblical accounts of creation for the religiously inclined. Even though it sold astoundingly well, after the floodgates of religious indignation opened,

Vestiges

admirers largely kept silent, while its critics were relentless. Perhaps the most scathing review appeared in the enormously influential

Edinburgh Review

. At eighty-five pages, it was the longest article the journal had ever published. The reviewer was the Reverend Adam Sedgwick, the esteemed geologist and vice-dean of Cambridge's Trinity College, who fulminated about the absence of Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden and ridiculed the notion that human beings came from apes. Sedgwick was among those who were sure the book had been written by a woman, and he devoted much of his sprawling article to proving his case.

Sedgwick didn't spare Andrew Crosse. He sent Crosse a personal letter

admonishing him never to “meddle again with animal creations; and without delay to take a crow-bar and break to atoms” his “obstetrico-galvanic apparatus.” Sedgwick wasn't alone. Following the publication of Chambers's book, Crosse was widely vilified, and he became a Dr. Frankenstein in the most pejorative sense. His experiment had usurped the very role of the creator. A deluge of hate mail began pouring in: he was a “heretic,” a “blasphemer,” a practitioner of “dark arts.” Many newspapers took the same tone. In print, he was branded “a reviler of our holy religion” and a “disturber of the peace of families.” Local farmers stopped speaking to him. He was blamed for an infestation of locusts near Fyne Court. A reverend with a reputation as something of a fanatic was called in to conduct a public exorcism of the hills surrounding Crosse's estate.

The religious-tinged criticism hurt Crosse, but it was his fall from grace in the scientific community that really crushed him. Before

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

appeared, most of England's important scientific bodies simply avoided addressing the nature of Crosse's insects. The subject of life's origin was so sensitive that they would touch upon it only reluctantly. But the elevation of his experiment in this now infamous book meant he could no longer be ignored. He was subjected to an unprecedented level of scrutiny. Every aspect of his experiment was carefully parsed and found wanting.

Acarus crossii

, many of his peers mused, was nothing more than the common dust mite. He became a laughingstock in the scientific community. The nervous attacks of his youth returned with a vigor. He immersed himself in poetry and tried his hand at fiction, but he had never been much of a writer.

Many years later, Crosse was asked to write a comment for a book about the great historical events of the first half of the nineteenth century. He bitterly protested that he was an unwitting victim and that he had never claimed credit for any act of “creation.” He had simply been swept up by the conclusions drawn by others, caught in the tide of an increasingly acrimonious debate between those who saw the world and all its workings as explainable by science and those who saw the world through the lens of biblical creation.