A Brief History of Creation (19 page)

Read A Brief History of Creation Online

Authors: Bill Mesler

Darwin was in shock. He fired off letters to Lyell and Hooker, who had prodded him for years to publish quickly, lest his discovery be scooped. Now that he faced just such a scenario, his mentors came up with a plan to solve his dilemma: they would announce the discoveries of Darwin and Wallace simultaneously. Two weeks later, they presented the findings of both men at a meeting of the Linnean Society of London, where the announcement went almost unnoticed. It took three months for Wallace to hear of the arrangement. He accepted the news gracefully, though he had been left with little choice.

Despite having just lost a third child in infancy, a boy named Charles, Darwin rushed to complete his book. Within thirteen months he finished a compact version of the opus he had originally set out to write. It had a new title,

On the Origin of Species by the Means of Natural Selection

, shortened in later editions to

On the Origin of Species

. Though it sold extremely well, Darwin's book, never managed to outpace sales of

Vestiges

, despite the fact that the latter had already been in print for fifteen years.

From a historical perspective,

On the Origin of Species

was probably the most influential science book ever published. It was written in the same personable, autobiographical style found in Darwin's account of the

Beagle

expedition. His son later noted the book's “simplicity, bordering on naiveté,” which may have softened the impact of the new theory. In places, the book was eloquent, but at root it was, in Darwin's own words, “one long argument.” It was a lawyer's argument in the style of Lyell's

Principles of Geology

, where evidence was heaped upon evidence. Possible objections were anticipated and shot down before they could take root.

Darwin's description of the history of life finally saw the light of day on the twenty-fourth of November, 1859. According to Darwin's vision, individual species arose through the process of natural selection. Gone was the miraculous divine creator. In its stead was nature “daily and hourly scrutinizing, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working . . . at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life.”

From the day of its publication, the book generated a firestorm of publicity. Letters started to pour in to Darwin's home. Most of them were critical, but many contained praise. One of those who wrote was the novelist Charles Kingsley, a socialist and a priest in the Church of England, who said the book left him in awe. “If you be right,” he wrote, “I must give up much that I have believed.” The strength of Darwin's arguments gradually won over the scientific community. The transmutation of Lamarck, so radical and threatening, became the evolution of Darwin, so rational and coolly objective.

D

ARWIN DID NOT

deal with the “vital spark” Hooker had fretted over until near the book's end. Even then, the origin of life was treated almost as an afterthought. “There is grandeur in this view of life,” he wrote, “with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful

and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.” In a second edition released the following year, the phrase “having been originally breathed into a few forms or one” became “having been breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one.”

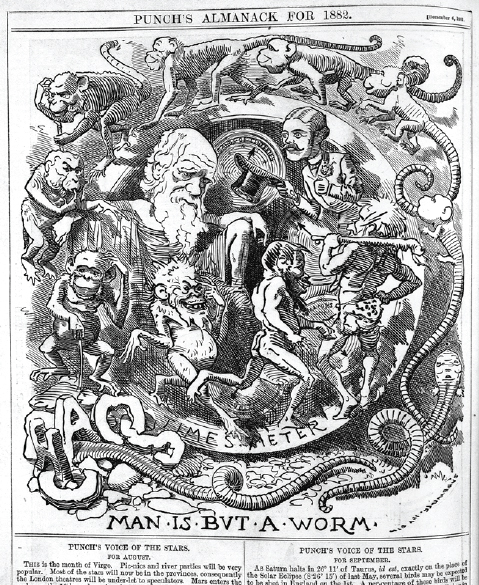

An 1882 cartoon showing the implications of Darwinism.

There is a certain logic to the fact that Darwin's book did not delve too far into the notion of the origin of life. It was a book based on careful

observation, crafted to navigate the criticisms that had once been heaped upon

Vestiges

. It was not a speculative book, and Darwin understood that his private beliefs on the subject of life's ultimate origin would be just that. The phrase “by the Creator” was added to mollify Darwin's critics in religious circles. Darwin would come to regret having made the change, and it would be pulled from the third edition.

The way Darwin dealt with the origin of life was disappointing to many in the scientific world, including some in the close circle that was forming around him. They could see in Darwin's theory the same implication that Darwin's religiously minded critics would: life was completely the product of the forces of nature, nothing more. Even in the editions of

Origin

that didn't contain the explicit reference to a “creator,” the allusion to life being “breathed into” something was easy to interpret as more than just overly cautious science. It smacked of cowardice.

One of those critics was Richard Owen. If there was a living embodiment of just how far

Origin

had carried evolution into the mainstream of science, Owen was it. Staunchly conservative and religious, Owen had once sneered at the very idea of transmutation. Within a few years of the publication of

Origin

, Owen began sneering at evolutionists like Darwin who he felt had not gone far enough.

In 1863, Owen published a book review in the pages of the

Athenaeum

, one of London's most important literary magazines. The subject was ostensibly a book on microscopic organisms that delved into the issue of spontaneous generation, but Owen used the forum to throw criticism Darwin's way. Owen's name had been left off the masthead, but Darwin immediately recognized his old friend's caustic style and the ideas he knew Owen held.

In his article, Owen criticized Darwin for ignoring the body of evidence that microscopic organisms could arise spontaneously in mud, which would have made

Origin

a more complete explanation for the existence of life. He also took Darwin to task for his remark that life had been mystically “breathed” into the first organism, ridiculing Darwin for having described the first appearance of life in what Owen, relying on a once widely used expression referring to the first five books of the Old Testament, characterized as “Pentateuchal.” Owen continued the argument

three years later in his book

On the Anatomy of Vertebrates

: “The doctrines of the

generatio spontanea

and of the transmutation of species are intimately connected. Who believes in the one, ought to take the other for granted, both being founded on the faith in the immutability of the laws of nature.”

â

Darwin was apoplectic. In a letter to the editor published in the

Athenaeum

, he asked, “Is there a fact, or a shadow of a fact supporting the belief that these elements, without the presence of any organic compounds, and acted on only by known forces, could produce a living creature?” But when it came to his choice of words on the appearance of the first life, Darwin became almost apologetic, saying that in “a purely scientific work I ought perhaps not to have used such terms; but they well serve to confess that our ignorance is . . . profound.”

Even before Owen's review appeared, Darwin was expressing much the same contrition about his word choice. “I have long regretted that I truckled to public opinion, and used the Pentateuchal term of creation, by which I really meant âappeared' by some wholly unknown process,” he had written to Hooker. Meanwhile, Darwin's views on the subject of the appearance of the first living organisms were themselves evolving.

By the next decade, with his reputation as a preeminent scientist beyond doubt, Darwin began to speculate more about that wholly unknown process, which he increasingly understood to be some form of spontaneous generation of organic life from inorganic building blocks. Again, his thoughts found their voice in a letter to Hooker. One, written in 1871, would become his most remembered on this topic. In it, Darwin wondered about the conditions that might have given birth to the very first living things. It would be, he guessed, “some warm little pond with all sorts of ammonia and phosphoric salts, light, heat electricity &c. present, that a proteine compound was chemically formed, ready to undergo still more complex changes.” It was a strikingly modern theory of how the origin

of life could come about, and would still be considered a reasonably good guess more than a hundred years later.

Darwin was still skeptical that such an act of spontaneous generation could take place in the Earth's current highly developed state. The problem was his own law of natural selection. The first organism would be, by definition, poorly adapted to survive. “At the present day such matter would be instantly devoured, or absorbed, which would not have been the case before living creatures were formed,” he wrote. As time went on, Darwin became more open to the idea of spontaneous generation in the modern environment. Others among the growing community of scientists called Darwinists were even more confident that this untapped piece of evolutionary theory, the “vital spark,” could be found, even that it could be recapitulated in a laboratory.

N

OT LONG AFTER

the publication of

Origin

, Darwin came under fire for failing to acknowledge his predecessors in the development of evolutionary theory. Darwin recognized the flaw almost immediately after publication, and he went about forming a list of those he should have acknowledged. His list eventually grew to include ten names, including that of his grandfather Erasmus, Lamarck, Wallace, and Aristotle, the last of which was an error by Darwin, who had mistakenly taken Aristotle's recitations of the views of othersâwhich Aristotle did not shareâas the Greek's own.

Today, the fact that the idea of evolutionary change was not first noted by Darwin has largely become irrelevant. He has become the de facto face of evolution, and the man behind the little fish with legs that people put on the backs of their cars. With the possible exception of Albert Einstein, no other figure is so closely identified with a scientific theory than Darwin is with evolution. And few besides Einstein come close in name recognition. Yet, while few really understand the principle of relativity beyond its iconic mathematical symbolization,

E

=

mc

2

, evolution's fundamental tenets are easily grasped.

Darwin transformed the way we view life. Considering the scope of the change, he did it in a remarkably short period of time. The rapidity

with which our perspective changed is owed partly to the fact that England's liberalized society was prepared for the new theory, and partly to the general state of the life sciences, which were advanced enough that the mounting evidence of evolution was too hard to deny. But Darwin was ideally suited for the task of explaining evolution. His caution and hesitation, even what some supporters saw as cowardice, was a useful tool in winning over a skeptical public and doubtful scientists. He did not try to go too far, too fast.

If Alfred Russel Wallace had not first mailed his essay to Darwin, Wallace himself might have been recognized as the “discoverer” of natural selection and thus come to occupy Darwin's place in the pantheon of science. But Wallace may have been ill suited for such a role. Darwin was the more accomplished scientist and writer, and close to the organs of power and knowledge in the most powerful and influential state in the world, the United Kingdom. Wallace was a man of no means. He had no ties to universities, no friends in influential places in the sciences, and not even a university degree. In his later years, he flirted with disreputable forms of spiritualism and mesmerism. Under his leadership, acceptance of the basic tenets of evolution might have been an even slower process.

Yet Wallace might have been more daring. He was much more willing to tackle, from the beginning, thorny issues like the subject of human beings' evolution from apes. Darwin's critics saw such an evolutionary implication from the day

Origin

first appeared. So did the most sympathetic of his scientific contemporaries. It took Darwin thirteen years to thoroughly address the question in his book

The Descent of Man

.

Still, Darwin did address it publicly. That was something he never attempted in any significant way with the question of the origin of life. Despite his reluctance to face the subject head-on, his impact was profound. Before Darwin presented his model of evolution, it was not really even a single question. People asked where the first monkey came from, or the first shark. Earlier naturalistic explanations of the origin of lifeâfrom the Greeks to Buffonâhad revolved around the question of the first of each species, but not the first

species

, period. Those who believed in spontaneous generation as the source of creation, like d'Holbach, believed that

the embryo of an elephant or even a human being could be the result of spontaneous generation from inorganic sources. This view was still held by some scientists in Darwin's time. Lamarck's concept was essentially a version of this. But after Darwin, the question crystallized. It became the search for a

single

living organism to which all other living things were related. Those who once wondered about the first of each species now wondered about a single first ancestor of all of them.